As well as spectacular photographs taken on the lunar surface and looking back at the Earth, Apollo astronauts took distant photographs of their destination.

So what? Anyone can take a photograph of the Moon right? True, but no-

Some of the more extreme idiots who insist we never went to the Moon claim that the Saturn V rockets never even left Earth. This is clearly nonsense, as the following photographs will demonstrate.

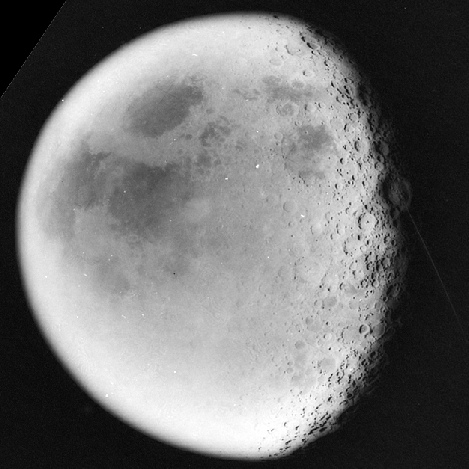

Just so we’re clear what we should be seeing, here is a picture of the Moon as seen from Earth. It is not a NASA image, or an Observatory image, it’s one I took with my own telescope from my garden. You might see it rotated differently, you might see slightly more at either edge thanks to the moon’s libration (its apparent ‘wobble’ caused by its elliptical orbit around us), but this is the pretty much what you will see anywhere on Earth. This kind of whole disk image is what we will be looking at here.

Apollo 8

The first example comes from the first human circumlunar expedition. Magazine 14 of the mission photographs shows a number of photographs of a retreating Moon as the astronauts return from their celestial Christmas rendezvous.

The first full disk image of the moon is AS08-

So, we know it’s an image of the Moon taken on the way home from it (not, as this NASA site claims, two days before it got there!), Let’s compare it with what should be visible from Earth.

AS08-

So, what differences do we see? Well, for a start the terminator line is convex on the view from Apollo, but concave when seen from Earth. We know the location of the terminator is roughly correct because it follows the same line of features. The Stellarium time is set at Trans-

The other major difference is what can be seen. If you look both at the Stellarium image, and the picture I took shown at the top of this page, there are obviously features showing that are either not normally visible from Earth, or never visible at all. Ever.

The most obvious features are the bright spot of the Giordano Bruno crater, the bright stripe near the eastern limb ahead of King crater, and the dark spot of Tsiolkovskiy. Giordano Bruno can be seen during a favourable libration, but as Stellarium shows this was not one of those occasions and the area to the east of it is not visible from Earth. Tsiolkovskiy was only discovered by Luna 3 in 1959, and, like King crater, is not visible from Earth.

Also just visible at the very southern edge of the disc below the freckles of Mare Australe is the high albedo spot of Fechner C crater, another one not visible from Earth. Mare Australis can be viewed during favourable librations, but not from Earth on this occasion.

Obviously then something took this photograph at the Moon. The fact that we have video footage and photographic evidence of Apollo astronauts taking those photographs is, to all but the wilfully ignorant, proof that it was a person.

Apollo 10

Apollo 10 also saw fit to take photographs just after TEI, and the first one to show a complete lunar disk is AS10-

The photograph below shows the Apollo 10 image compared with Stellarium’s view of the Moon at TEI from India, which would have been in view at that time.

The final image of the Moon in the magazine, AS10-

Zoomed and cropped view of AS10-

Apollo 11

Apollo 11 has a couple of contenders for examination here, one black and white, one colour.

The black & white candidate is AS11-

AS11-

This time Apollo doesn’t even give us a terminator -

A couple of photographs later we have AS11-

AS11-

AS11-

AS11-

One final photograph of the Moon from Apollo 11 is on magazine 38, and is AS11-

AS11-

As we can expect, there is very strong agreement between the view suggested by Stellarium and the Moon photographed by Apollo 11. We can be fairly certain about the time chosen because the next photograph in the magazine, a picture of Earth, can be pretty accurately dated at 02:30 on the 24th.

The view is not 100% identical -

Apollo 12

Apollo 12 gives us a little treat in terms of this discussion, in that it shows us images of the Moon on the outward as well as return journey. The outward portion is discussed in the ‘Clouds Across the Moon’ document here, but there is no harm in re-

Magazine 50 features numerous photographs of Earth on the outward portion of the journey, and these can be dated reliably using satellite meteorological data as before.

Before entering lunar orbit (as depicted in the magazine), there are a couple of photographs depicting the Moon as a thin crescent. The difference here is that while homeward bound photographs tend to show portions of the lunar far side east of the horizon (as we see it), these images show the Moon as viewed from the west.

The first one is AS12-

AS12-

Just so we know what we’re looking at, the terminator line on both images falls at the western edge of Mare Vaporum, and the eastern horizon of the Apollo image cuts across Mare Tranquillitatis. This is quite obviously not a view that can be had from any terrestrial viewpoint, and the fact that it is in such a narrow window time window shown by the Earth photographs makes it even more obviously taken from exactly where Apollo 12 was supposed to be.

A few frames later in the same magazine we have AS12-

AS12-

The terminator line is consistent with the time and location suggested: coasting around to the lunar far side preparing for LOI.

The homeward bound photographs of the Moon are shown in magazine 55. Unfortunately it shows no images that can be used to date them precisely, but the Photographic Index labels them as being of TEI, with the first part of the magazine showing photographs taken from lunar orbit.

The first one is AS12-

AS12-

Now that Apollo 12 is on the way home the view of the Moon is almost full, but the view from the departing spacecraft shows a ¾ one. The terminator line shown is the eastern one, and would not be visible from Earth. It crosses the far side crater Langemak, amongst others. The large crater just below centre and west of the terminator is Pasteur, which is only occasionally brought into view by libration.

The final view of the Moon in the magazine is AS12-

AS12-

In this image two things have changed -

Apollo 13

Apollo 13 took many lunar photographs despite the enforced brevity of the mission.

The first useful one meeting the criteria for this mini analysis is AS13-

It is a full disk, and occurs between photographs of closer and distant lunar images, and before a photograph of Earth dated at 05:00 on the 15th.

AS13-

Tsiolkovskiy is visible , and quite a considerable portion of the moon to the east of it, this is a photograph that could not have been taken from Earth. The size of the Moon suggests that it was taken shortly after the TEI burn that sent it safely back home, let’s say 02:00. Stellarium shows the view that would have been seen on Earth, and it is clearly not the one photographed here.

A different magazine also shows a picture that must have been taken shortly after TEI, AS13-

AS13-

The angle of view has obviously changed now, but while the visible features are not far away from a normal terrestrial viewpoint, there is still substantially more visible. The estimate of 03:00 is not unreasonable, as AS13-

By the final image of the Moon in this magazine, AS13-

Zoomed, cropped, rotated and brightened AS13-

The time of 12:00 is again based on an estimation, but the terminator line is a good match.

Only by the last image of the Moon in magazine 62, AS13-

AS13-

Apollo 14

Apollo 14 did not do well in terms of photographing the entire lunar disk -

AS14-

The view seen by the Apollo astronauts is little different to that as seen from Earth in this image, but it is still full compared with ¾ full, and still shows features that were not visible from Earth at the time of the photograph. Once again it is obviously a photograph taken from a vantage point of an Apollo craft emerging from the far side of the Moon on an earthbound trajectory.

Apollo 15

Apollo 15 fares slightly better, supplying a few images appropriate to this little study. Two of the magazines consist solely of lunar images, but Magazine 88 shows images of the lunar surface, lunar orbit and Earth taken from lunar orbit as well. This mission also featured the first use of the mapping camera, and one magazine specifically shows whole disk images taken after TEI, which happened at 21:22 August 04 1971.

The first mapping camera image of a full lunar disk is AS15-

Apollo 16

Apollo 16 also has little in the way of lunar images to add to this study, and the photographs that do match the criteria required occur on magazines with no other supporting features such as photographs of Earth. The mapping camera does have a good record of post-

The first (almost) full disk post-

Apollo 17

Humanity’s final expedition to the lunar frontier contains many fine photographs, but only a couple of the entire lunar disk that are of use here -

The first photograph of the two is AS17-

AS17-

On this occasion the eastern terminator falls across the far side of Tsiolkovskiy crater, which we know can not be seen from Earth. The western terminator cuts across the western edge of Mare Humorum, which is exactly where it should be, as shown below.

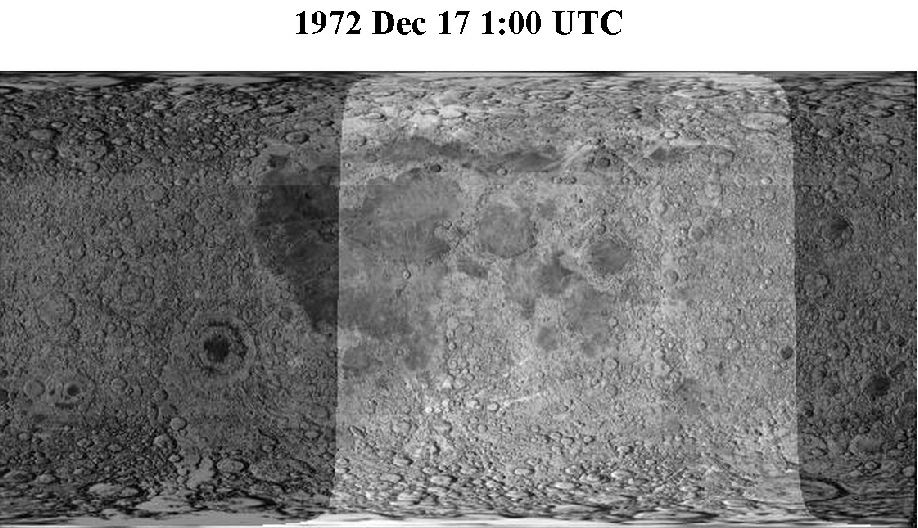

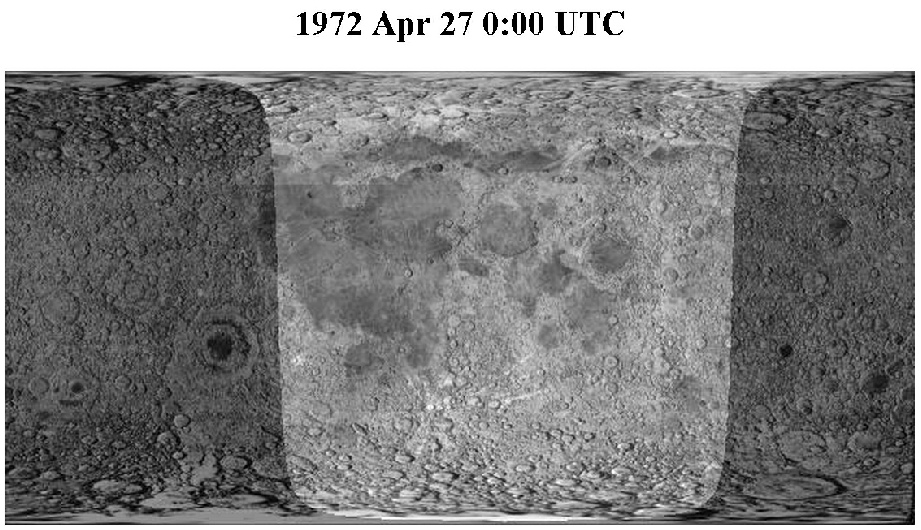

Fourmilab projection of lunar night & day at 01:00 on December 17 UTC

01:00 has been picked as a reasonable time, but it does fall after TEI, and before the EVA pictured later, which took place at 20:27.

We also have an image taken by the mapping camera after TEI. Like all images on that magazine they are not whole disk views, but we may as well include it for fun.

A photograph of the Moon taken after that event is AS17-

Zoomed and cropped AS17-

As there is still a couple of days before splashdown it’s not surprising that the view from Apollo 17 is still not the same as the view from Earth. Even a low quality image of a very distant Moon contains evidence that shows that the camera that took it was not on terrestrial ground, Or indeed any ground at all.

Conclusion

So, what have we proved here?

Well, we have proved pretty conclusively that the Apollo missions returned photographs of the Moon that could not have been taken from Earth.

All photographs taken during the initial post-

Photographs taken nearer the Earth still show differences to the views Earth-

Fourmilab Moonviewer projection of the terminators August 4 1971 at 22:00. Red X marks the location of Pasteur & Hilbert craters.

Compare this with the first full disk image at the end of magazine 88, AS15-

AS15-

The straight terminator indicates that Apollo was directly above it, rather than at an angle. In contrast to the normal state of affairs, the view from Earth is an almost full Moon, compared with a half-

AS15-

The terminator line on the Hasselblad image shows a very similar path to the one on the post-

The video below shows the sequence of mapping camera photographs as the spacecraft returns home. Pasteur crater is easily identifiable crossing the terminator, showing that the amount of time passed is not enough to account for the change in shape of the Moon.

AS16-

The terminator line here is running some distance east of three craters that are not visible from Earth: Ostwald, Ibn Finas and King (King has a pronounced central peak and can be found in the bottom half of the picture, right of the centre line, and is indicated by a red cross in the image below. The terminator cuts though Tsiolkovskiy crater, which is just cut off on the image above.

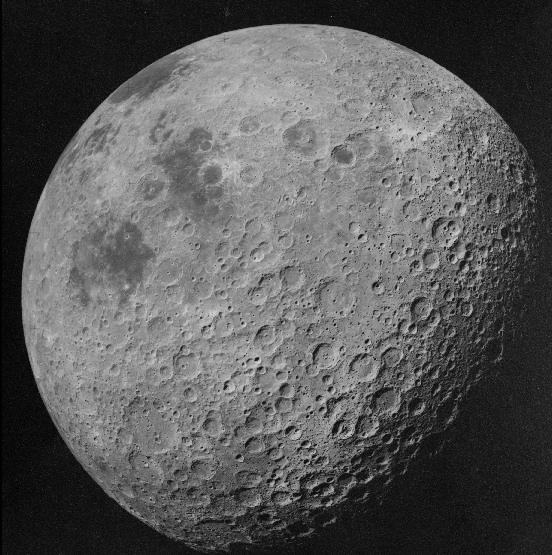

Fourmilab projection of sunlit areas shortly after TEI

A later mapping camera image (AS16-

AS16-

There are other images of a full lunar disk from the mapping camera, but they are for the most part over-

AS16-

At around 3 o’clock on the lunar face, on the terminator, there is a crater with a prominent peak. Once the brightness is adjusted, this crater can be identified as Hilbert,and the dark shading of the lunar maria can also be seen. In order for Hilbert to be on the horizon, we need to move time along about 36 hours, as can be seen below, and this is entirely consistent with the journey homewards that the mapping camera images illustrate with an ever shrinking lunar disk.

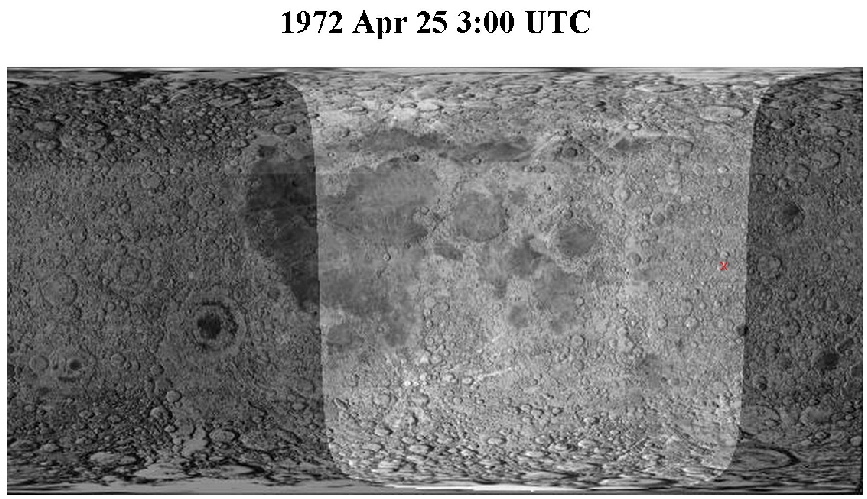

Fourmilab view of sunlit areas on the Moon at midnight, April 27 1972

If this is compared with the Hasselblad image, we can see that they were taken at roughly the same time, but the view given by Stellarium shows that we are still not looking at it from a terrestrial perspective. Not surprising, as we are still 19 hours from re-

The view of Tsiolkovskiy crater is fabulous, and the extended shadow falling from its central peak is something human eyes would never see from Earth.

The second Hasselblad image is shown below. The detail is not as clear because the Moon has been photographed from a much greater distance

AS16-

As with Apollo 15, it is possible to string together consecutive mapping camera images from the post-

Die-

In order to support the idea that the missions were hoaxed, the process of faking it gets ever more complicated. Conspiracists now have to concede that something was orbiting the Moon taking photographs at the same time as the missions were supposedly being faked on Earth. It really was easier to actually go to the Moon than provide the fakes the Apollo deniers claim they are.

The study given above proves nothing on its own, but it is yet another straw of evidence on an already over-

We went to the Moon. Only idiots, morons, liars and fraudsters claim otherwise.

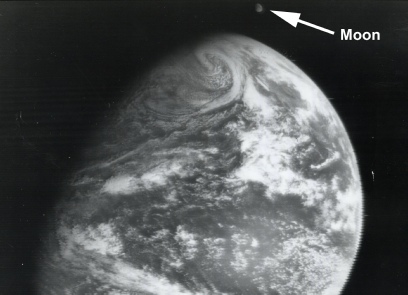

This particular facebook poster either hasn’t checked the timeline to see when these images were taken, or he has and is just assuming what he should see. These images of Earth taken from space (from here and here, illustrate perfectly that the the view depends on the position of the observer.

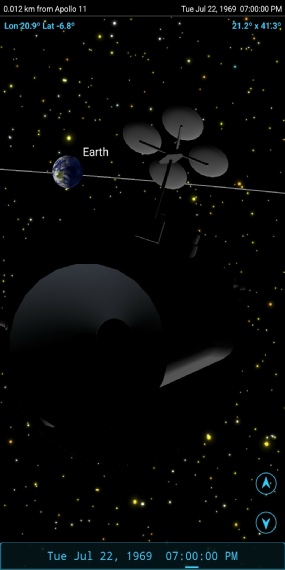

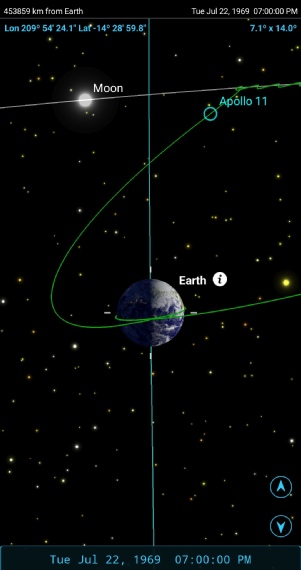

You don’t even have to put much effort into proving this. Just a few ££ gets you the Apollo missions add-

We can do a similar exercise with the Apollo 12 images the facebook poster uses (eg AS12-

Compare the photograph above with the image shown rigth in the 16mm footage (available here).

The terminator curvature is still not that of a terrestrial perspective, but the lunar features visible are much closer to that seen from Earth, although there is still some way to go before it becomes an exact match.

Apollo 08 16mm video still.

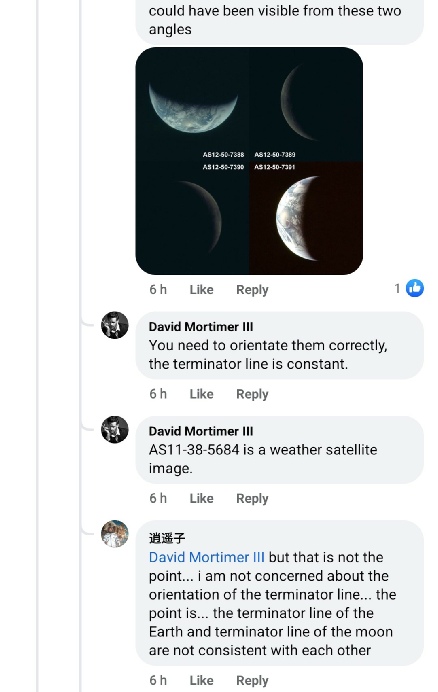

We get a perfect exampled of just how poor the average hoaxtard’s understanding of 3D space, and how little effort they’re prepared to go to to understand the missions and the imagery they produced, in a facebook exchange about what Apollo astronauts could see of the moon.

The basic tenet of the post is that a NASA film discusses astronauts taking photographs on the way to the moon, while the astronauts themselves say they couldn’t even see the moon until they got there, thanks to the orientation of their spacecraft. They then go on to cry foul at the moon’s phase, saying that they should be seeing a different phase compared to that of the photograph used in the film. Here’s the exchange:

This is the chart (right) he’s talking about, where he’s identifying the lunar phases as if he’s viewing it from Earth.

To be fair, one of them is grasping the idea that the view might not actually be one from a terrestrial perspective, but it’s pretty obvious that they’re struggling with grasping the whole “universe is a three dimensional thing” concept.

What the person suggesting it was taken from the side also claims is that it would not be easy to determine if it is correct or not.

Let’s see.

They identify the image used in the film is one chosen from a sequence in magazine 18 (AS08-

Here’s the image used in the film, versus ones from those magazines:

It’s worth pointing out that the film version is actually reversed -

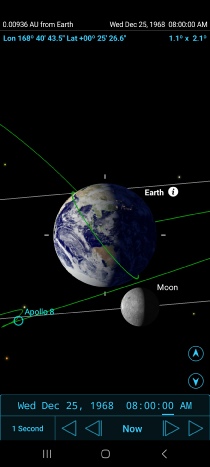

So, if we put a time on the terminator of around 08:00 on the 25th, what should we see? Let’s see what Astronomy software Celestia (below left) and SkySafari (below centre) suggest.

Hmm, turns out it was pretty easy to find out what the view would be like. They can argue all they like that well, it must have been taken automatically, but given the way the photographs were taken that would be pretty much impossible to achieve.

Left: AS10-

Although this time there are many features that are not permanently obscured from Earthbound viewers, it should be evident from Stellarium’s view that at the time the photograph was taken they were not visible. The time can be confirmed again by the line the terminator takes across the lunar surface.

It should also be obvious that the half Moon seen from Earth is presenting a different phase to the homeward bound astronauts.

Again, the Earth image matches perfectly what it should show for the time the image was taken, and the moon is viewed from the side as the spacecraft anticipates where it will be by the time their extended orbit intercepts it.

The app shows not only that the images show exactly what they should, but why: the Apollo 11 craft is not in a direct line of sight between Earth and moon, because the moon has moved on and Apollo I effectively looking to one side.