Happy Trails

Straydog has made numerous comments of late relating to the appearance of astronaut trails, as seen in surface photographs and also in orbital imagery.

We’ll deal with them generally, but first let’s look at it in the context of a long comment he made about the trail to Little West crater carved out by Neil Armstrong.

He starts off with this:

In the 1969 surface photography (specifically the panoramas taken by Armstrong), Little West Crater is remarkably difficult to identify.

The Scale Problem: From the surface, a 30-

I’m not sure why he feels it should be a massive dominant landmark when it’s 50-

It is, however, perfectly visible if you’re prepared to look (see this page for more).

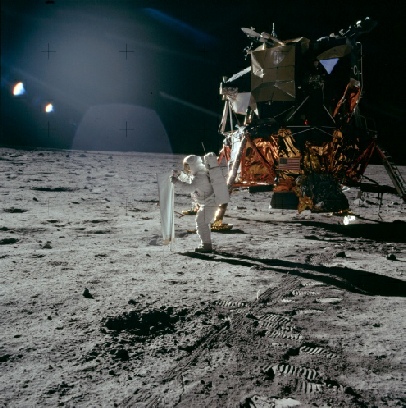

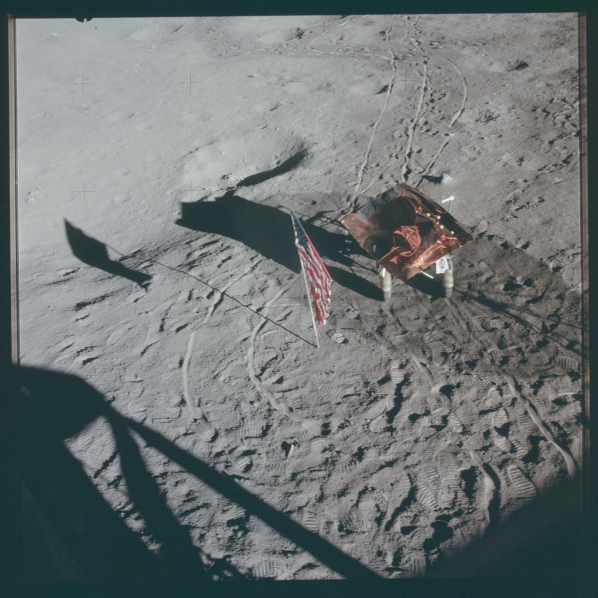

AS11-

So the fact is, it’s there in the photos. It’s there, it’s visible at eye level, why else would someone wander over there if not to investigate it?

He then claims this:

Armstrong supposedly ran over to it, took a few photos, and ran back. But the photos he took (the AS11-

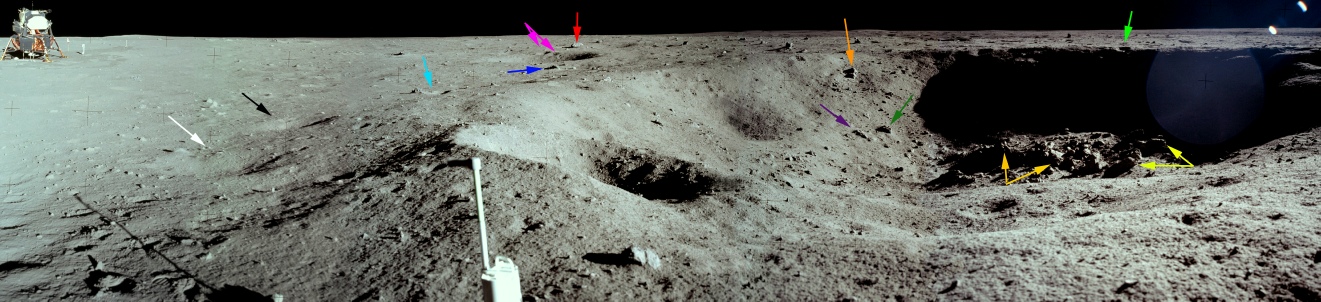

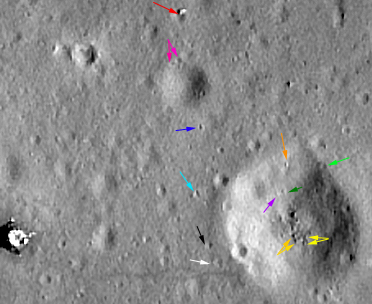

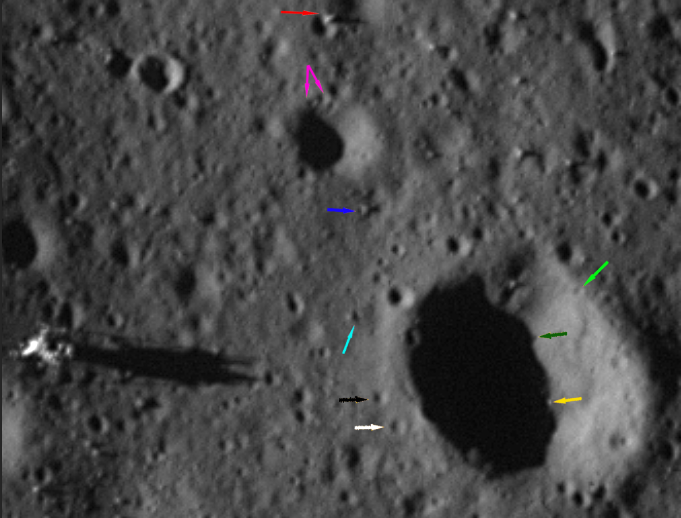

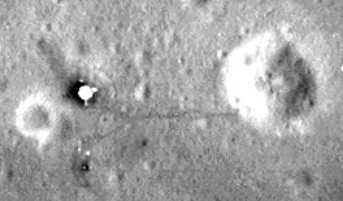

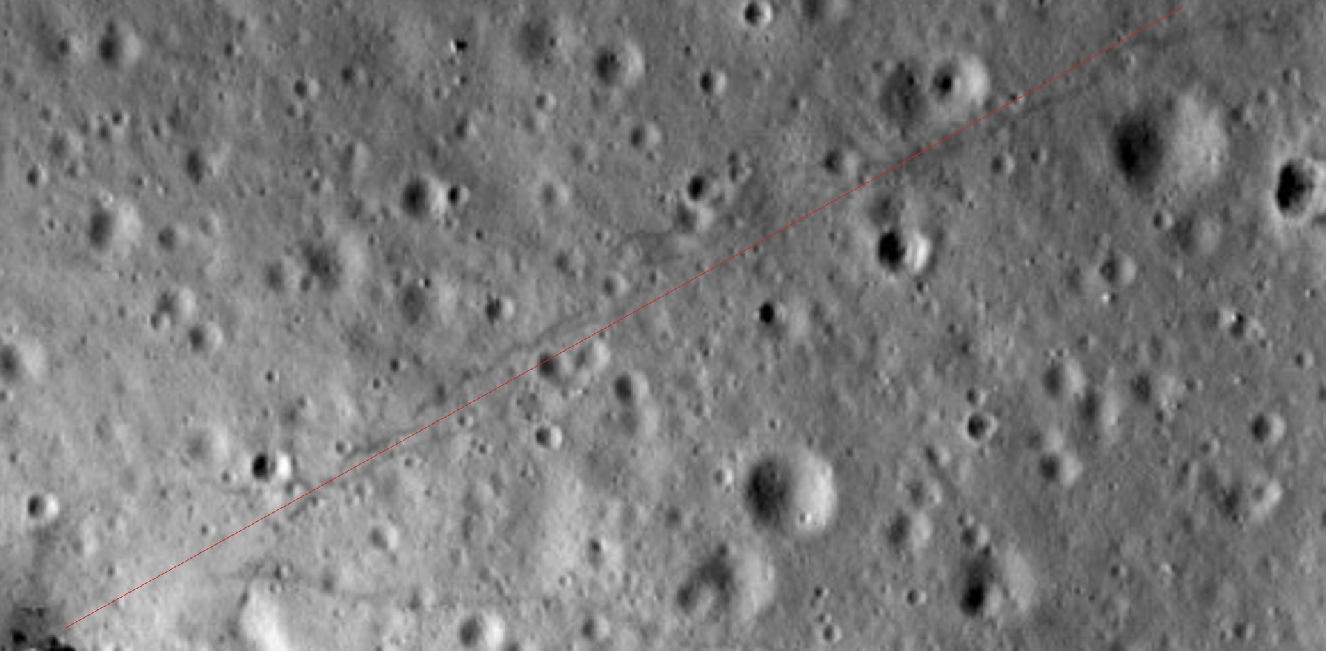

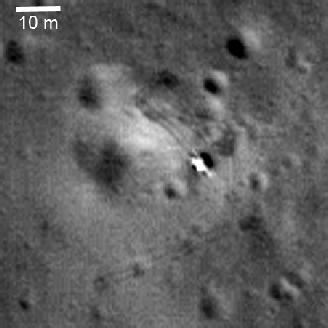

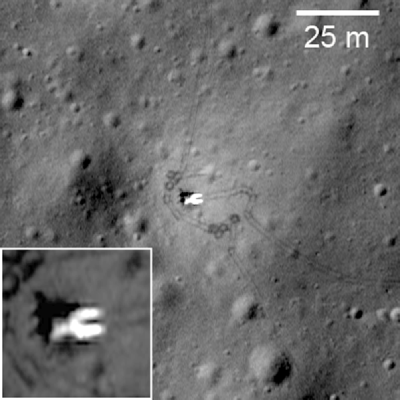

Several questions are begged here. How is he defining “significantly smaller”? Where are his measurements? How is he determining that it isn’t big enough? Just so we’re all on the same page, here’s Little West as photographed by Armstrong, and by the LRO and India’s Chandrayaan-

I’ve shamelessly lifted those images from the my own page linked to above, which is why there are pretty arrows identifying the same features visible in all of them.

This paper certainly has no issue with any of the details in the surface photos when compared with orbital images, and they’ve done this by the crazy method of actually measuring things, instead of spouting bullshit on the internet.

One of his criticisms of the tracks visible in LRO images (and presumably the ones also visible in the many Danuri images (see here) is that they end precisely at the spot where Armstrong would need to be to take the photos. It’s almost as if he was there.

Now to the meat of his criticism: the appearance of the trails themselves. He makes this grand claim:

“Official Science: Disturbed lunar soil should be brighter (high albedo).”

We aren’t given any sources for this claim, but he does says this should be asked of every Apollo defender:

“If the Moon's surface is covered in 4 billion years of sun-

There’s a bit of a contradiction there, in that bleaching implies brightening, but the general consensus is that the lunar surface has been ‘tanned’ by the sun, with sub-

He’s assuming that the lines visible in orbital imagery are drawn by some unnamed CGI artist somewhere, rather than (as he describes it) human feet spraying unbleached dirt everywhere. As he puts it: “chaotic, messy footprints of a man running in 1/6th gravity”.

He even draws attention to this explanation in his discussion of the ‘boulder ring’ in Apollo 12 images:

“According to the "official" science of the Moon, the surface is covered in a layer of fine, dark dust (regolith) that has been weathered by space radiation. Beneath that thin layer, the soil should be lighter and more reflective because it hasn't been "tanned" by the sun for as long.”

What he’s not taking account of, however, is what’s been described as the ‘lunar disturbance effect’, something first noticed during the Surveyor missions -

Here’s another claim:

“The track to Little West is much darker and more defined than the tracks around the LM where the astronauts spent hours working. Why would a single 2-

Not sure where he’s getting that judgement from -

The heavy activity around the EASEP and the back and forth to the TV camera are very obvious, just as they are in the surface photos. He then makes a similar set of claims about the Apollo 14 tracks.

His main gripe here is that the Modular Equipment Transporter has two wheels, but the view from orbit only shows a single track! Oh noes! He does point out that the main defence for this is that the footprints and tyre tracks would merge into one, but doesn’t think this is a good argument. He doesn’t say why this isn’t a good argument, but hey, trust me bro!

Let’s fill in some blanks. The MET weighed, on the moon, around 60 lbs, fully laden. It’s heaviest mass was when moving the ALSEP to its location west of the LM. The tyres, inflated by nitrogen at 1.5 psi, were roughly 1 metre apart, 10 cm wide, and crucially had no tread. That’s important.

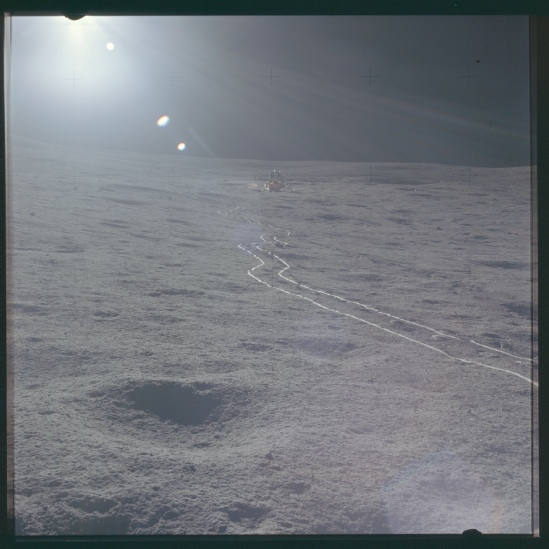

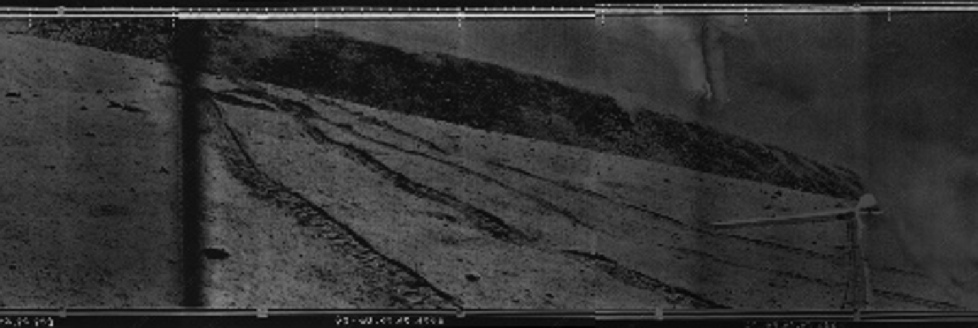

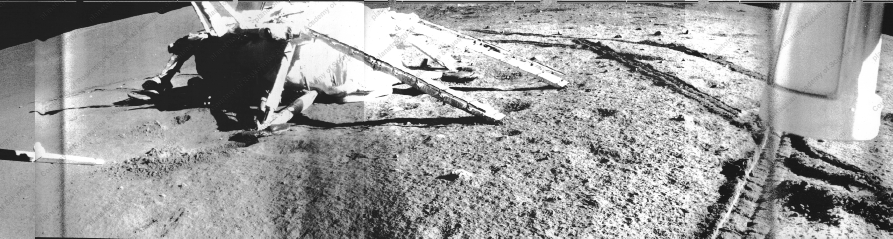

A popular image from Apollo 14 shows the tracks left by the MET. The Apollo 14 Preliminary Science Report actually says this image shows the tracks on the way to Cone Crater, but it is more correctly recorded elsewhere as being taken at the ALSEP.

The sun us behind the LM here, in the east -

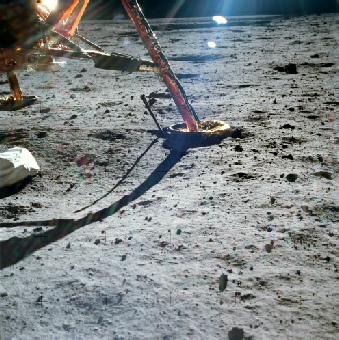

The view below shows a close-

Stray has this to say about it:

“On the real Moon, the vacuum-

That’s exactly what we see here -

On the way to Cone, Ed Mitchell describes how the MET behaves:

132:27:32 Mitchell: And, Houston, I'm trailing along behind Al now. I'm starting to catch up with him. And -

And

132:28:10 Mitchell: It leaves gaps every now and then as it bounces.

While they though it was a worthwhile piece of kit, it was hard work:

if you shake the MET too much, you're afraid you're going to shake things out. So, trying to do that loping gait, that I liked, was very difficult to do with the MET behind you. You had to more use the (foot-

And it was certainly twitchy on the lower lunar gravity, threatening to tip, as well as being prone to bouncing. They even resorted to carrying it at times.

So, while in ideal conditions we would have a smooth track, in reality we have astronauts struggling to control it, pushing hard on the surface. As for stray’s claim:

“it should leave two parallel tracks with human footprints in between or to the side.”

He’s obviously never pulled or pushed anything heavy before.

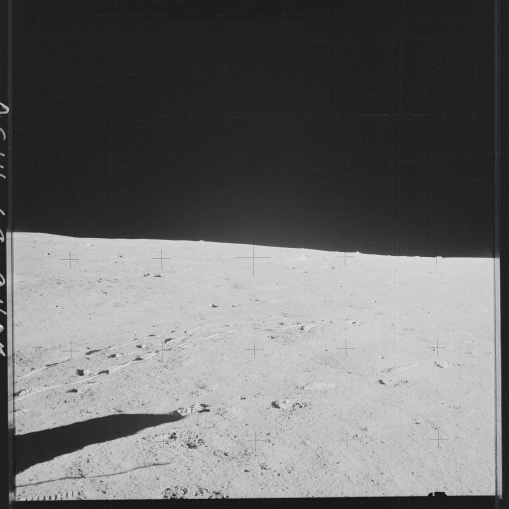

This image, taken en route to Cone, shows prints directly in the MET tracks, churning up the surface in the process.

The glare of reflected light on the compressed tracks (also evident in some of the more intact boot prints) makes the tracks seem more impressive than they are. This view from the LM show them in a less reflective light. Ahem.

These MET tracks are surrounded on all sides by ground disturbed by astronaut feet. Why would they stand out from lunar orbit any more than the much wider darker ground?

Stray isn’t happy about the track leading to Cone as seen in LRO images:

“The LRO Image: The track leading up the hill is as straight and clean as a pencil line. It shows zero evidence of the struggle described in the mission transcripts. It looks exactly like someone drew a path on a computer screen to connect the LM to the crater rim.”

Straight and clean you say?

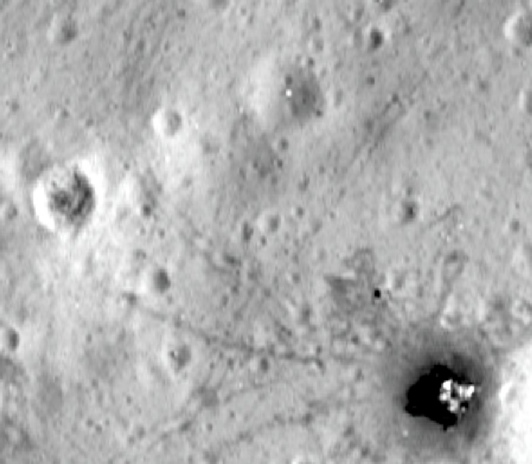

Looks more like they took a meandering path, dictated by craters and conditions underfoot as they managed two wheeled cart. If you’re unhappy with the LRO being the probe used here, check out the others that are available, showing the same thing.

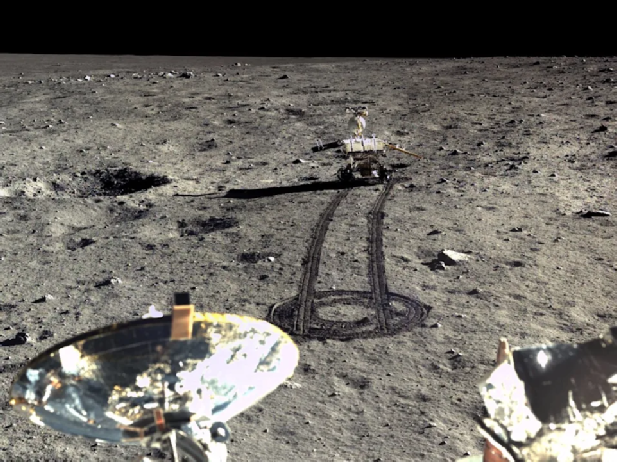

When you have vehicles that operate without a person helping it along, and even better tyres with a tread that will disturb the surface, then you do indeed get twin tracks. Those tracks, whether viewed from the surface or orbit, whether they’re American LRVs, or Chinese, Russian or Indian probes, all show darkened tracks relative to the surface.

Lunokhod 2 (see my page here):

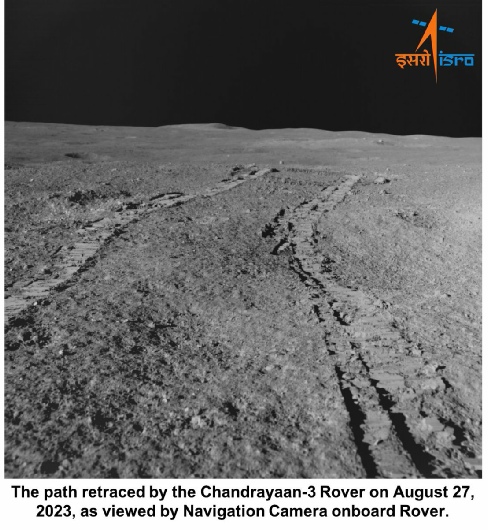

Pragyan lander. Note the deep shadows where the tracks are also deeper. The tracks aren’t very wide, and don’t show up well from orbit, but even when they are found, they are dark, not light (my analysis of image ch2_ohr_ncp_20231030T2358211985_d_img_d18).

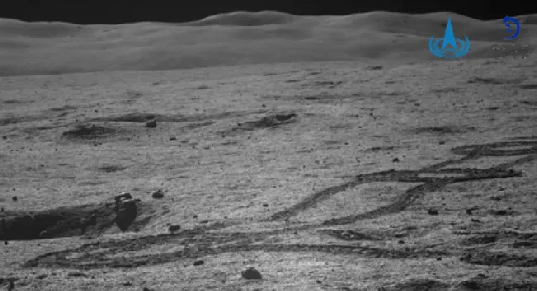

China has several landers on the lunar surface. Starting with the first, Yutu (Chang’e-

Yutu 2 (Chang’e-

To summarise: it doesn’t matter whose boots, or wheels, are on the ground, if they disturb it then the nature of the surface changes. Those changes manifest themselves as dark lines on the surface. How easily they are seen depends on lighting, and the level of disturbance, and the nature of the surface itself.