This page will looks at some of the things visible in Apollo visors (or to give it its Sunday name, the Lunar Excursion Visor Assembly, LEVA). Mostly this consists of Earth, but other things can be seen from time to time.

First up, Apollo 11.

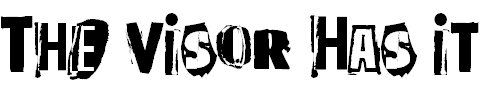

It is one of the most famous and iconic photographs ever taken, an image that was reproduced on countless newspapers, magazines and websites. It has been dissected and discussed many times. It is AS11-

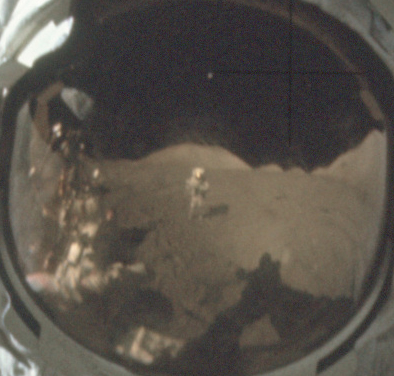

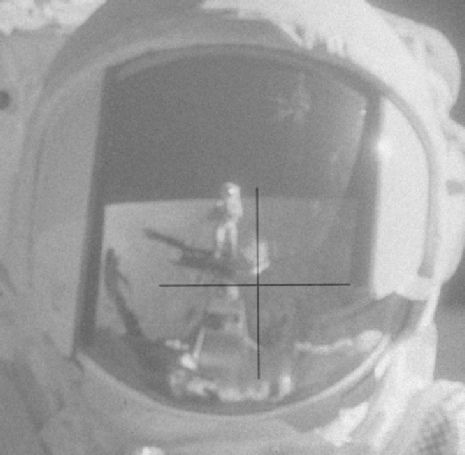

What I want to focus on here is a small detail seen in the visor, and I’ve zoomed in here to the version seen on the front cover of Life Magazine, using my own copy:

The small detail in question is the little blue dot left of centre of the visor. The dot has been identified as Earth before, but what I want to do is just give a little more back up data to the idea that this is what we are seeing.

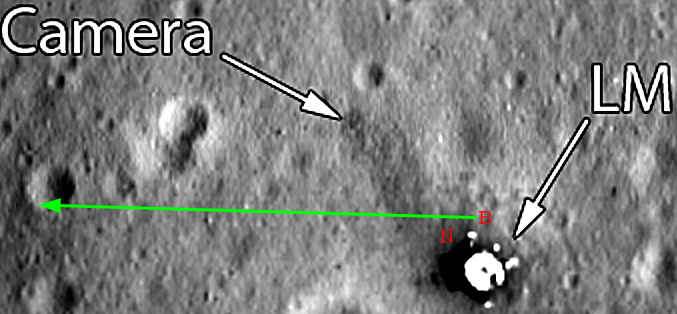

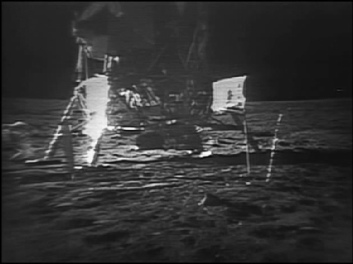

So, the first thing we need to find out is where was Earth at the time the image was taken? We know what time that was, because it is recorded in the ALSJ here, and if we skip through this youtube video to the relevant points, we can see the moment where it was taken. Below is a the moment (left) when the image prior to this one in the magazine was taken on the right is the moment Neil takes this famous photo.

As you can see, Buzz moves out of shot of the TV camera between photos, so let’s check that we have Neil in the right place before we do anything. Before we do that, we need to reverse the visor view so that the mirror images what we can actually see.

Neil has moved to a position in line with the engine bell, roughly the same point reached by Buzz’s shadow.

If you follow the video from the point where 5902 is taken to the point where Neil reaches the place where he takes 5903, you can see the top of Buzz’s shadow move to that position as he goes off camera.

The position of the solar wind experiment to the right of Buzz’s shadow seems incorrect, but here we are at the mercy of perspective being distorted by the curve of the helmet.

GoneToPlaid has done some excellent work here that demonstrates the impact of the visor curve on the image.

To a certain extent I am replicating his work, but I refer to it only in passing -

You can also do that if you have any issues with what is being presented here.

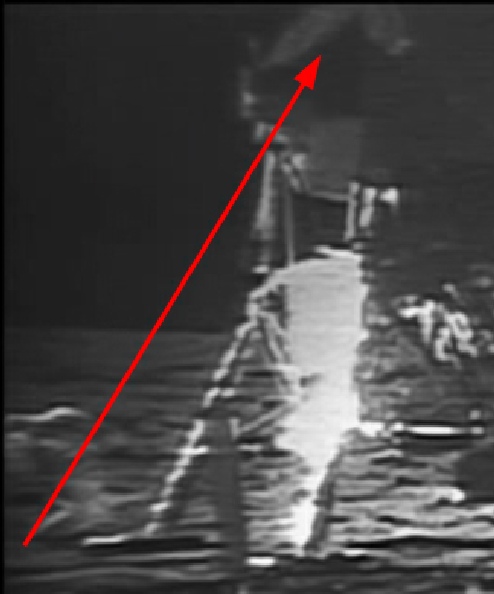

The key information here is that Earth is at an angle of just over 272 degrees from north (just past due west), and at an angle above the horizon of just over 59 degrees.

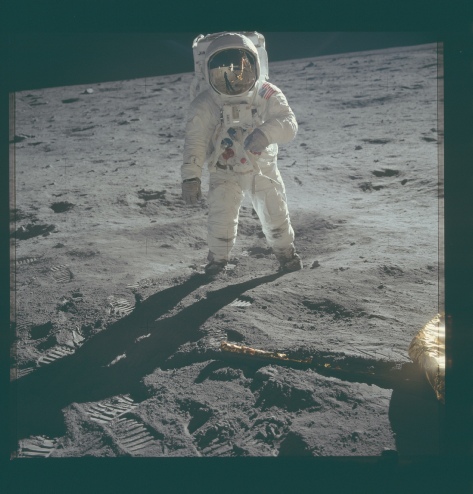

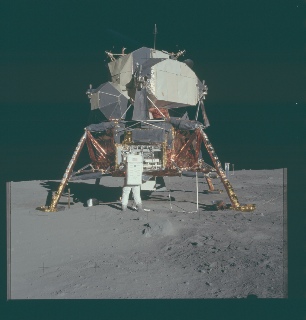

First things first, is Buzz facing the right way? Well, here’s the LRO’s view of the Apollo 11 landing site, together with the positions of Neil (N), Buzz (B) and the direction towards the Earth shown by the green arrow.

Now that we know where the two respective people were stood, we can try and work out whether Buzz was indeed looking at Earth in the distance.

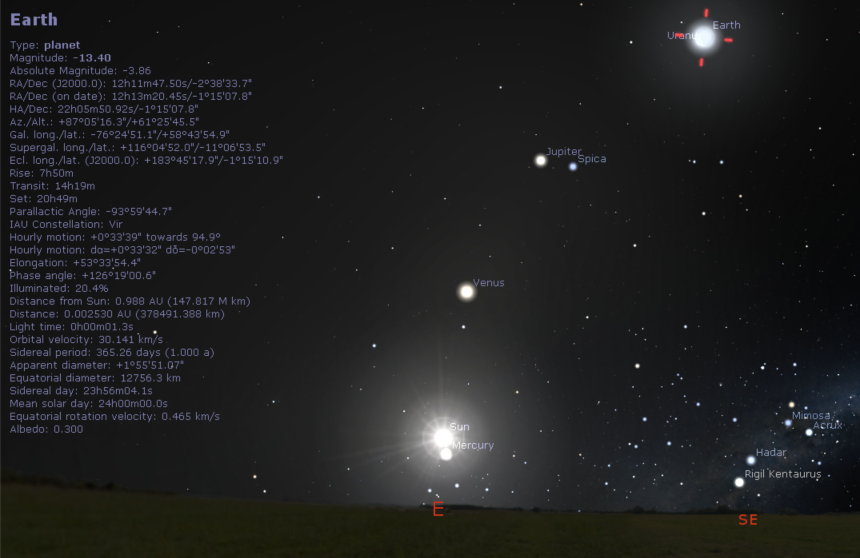

As we know when the photograph was taken, we can use astronomy software to see where Earth would have been in the sky at that time, as well as the sun. I use Stellarium, and right is an image based on a time of 04:15 on 21/07/69.

A bit of head tilting should tell you that this would put Earth somewhere over Neil’s left shoulder, or right from Buzz’s perspective, and if you head on up to the visor photo you’ll see that this is indeed where it is.

The next thing is to see if it’s in the right place in the visor. To do that we need to reconstruct the TV view of the scene to show where Buzz was. I’ve done this by superimposing an earlier shot showing the scene to the left of the LM, and a version of Buzz taken from the flag ceremony, added in roughly the right place.

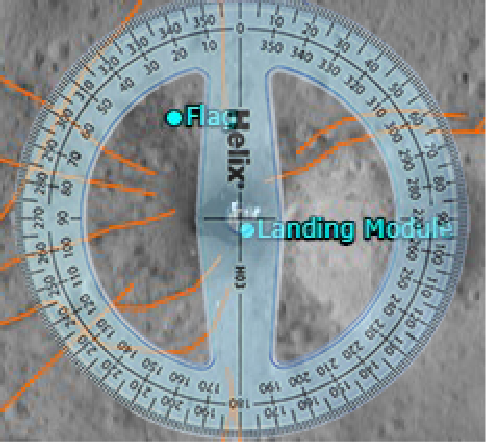

After that, it’s a simple job to use a protractor to draw a line at 59 degrees from the horizontal:

Seems that 59 degrees places the Earth quite high in the sky -

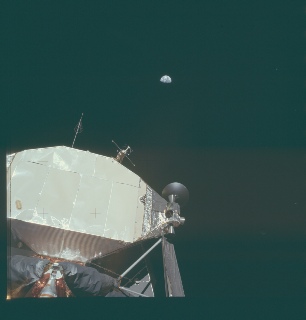

Well, we can get some verification from other images taken around the LM, specifically one showing the Earth, an Earth with time and date specific weather features.

Above left we have AS11-

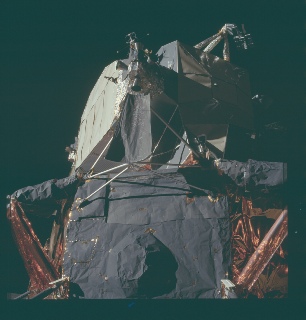

Buzz is very obviously at the base of the strut identified in the LRO view, as it is the next one around from where Buzz stood for his portrait. He is also looking in the right direction -

There we have it, roughly the same spot in the visor as the previous Earth image, although admittedly it is not of the same blue-

What about other missions?

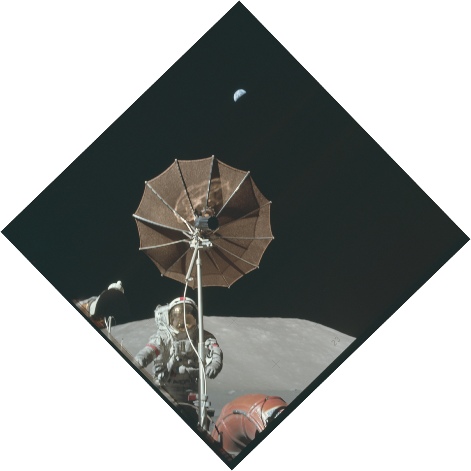

Apollo 17’s relatively high latitude and half-

Clearly visible is the feature known as the South Massif -

So far so good, but can we be sure it is Earth?

Well, we know what time the photographs were taken so we can plot in Stellarium and see where Earth should be, like this:

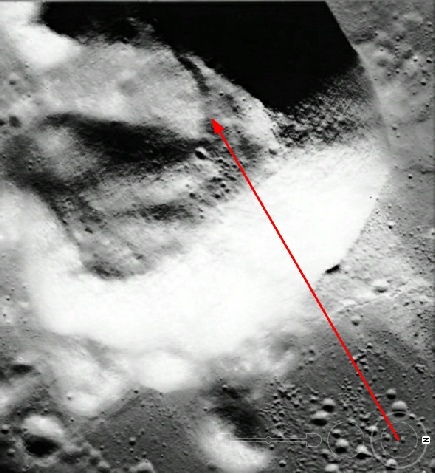

The key information here is that Earth should be at an angle of just over 240 degrees from North, and at an angle of just under 45 degrees from horizontal. We can draw on Google Earth here for some help to show that it is looking in the right direction.

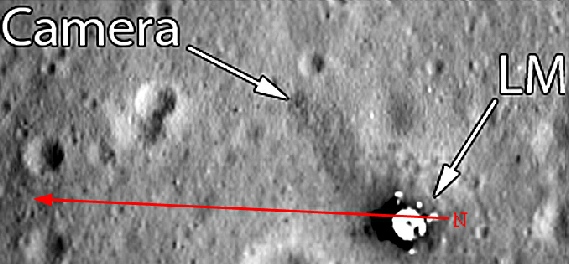

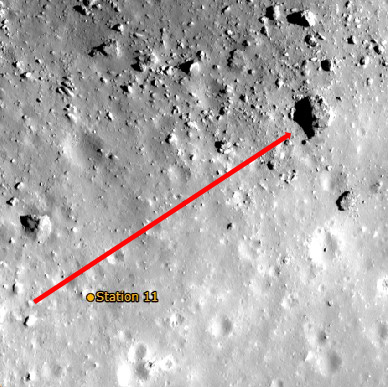

In the image below there is a red line drawn from the landing site through the centre of the southern Massif at an angle of 240 degrees from North. The landing site is centred on the compass rise, The Google view is rotated 90 degrees so that it matches the Apollo views better.

Next to the Google Moon view is a rotated AS17-

What more needs to be given to show that the pale blue dot in the visor is the Earth?

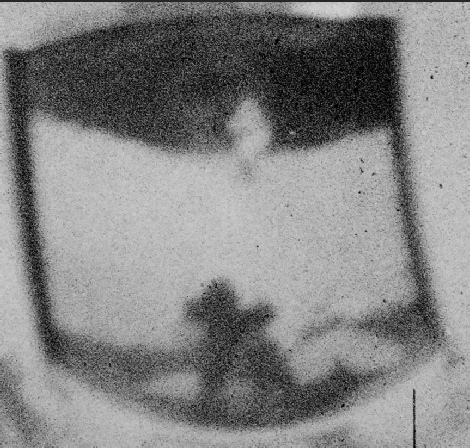

We could try one more thing, just for fun. The ‘March to the Moon’ site has some high resolution scans of Apollo images, and one of them is AS17-

I will be the first to state clearly that the image above right has been sharpened and adjusted considerably, but absolutely nothing has been added to the image. For my money, there is a blue-

To be equally fair and honest, there is no similar feature in the two preceding images, although these are arguably less sharp and show less visor.

Take your pick.

We can be even more speculative with the next photo -

It’s back of the envelope stuff, and his camera isn’t pointing directly at Earth, but it looks pretty much bang on for where the Earth is. It’s always possible that this one is the photo of the LM base -

There we have it, all done very simply and straightforwardly. Buzz’s visor image shows Earth, and it is Earth because the evidence all matches up with that.

The next question must be: are there any other examples of this? As it happens, there are.

AS11-

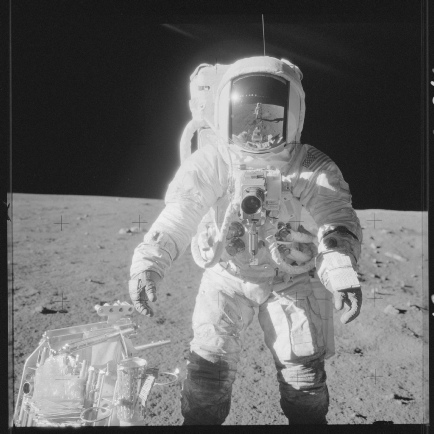

If you zoom in closely to the Alan Bean’s visor, you can see that there is a bright blob clearly visible. Is it Earth?

We know that Bean set foot on the lunar surface at 12:13 on 19/11/69, and here is what Stellarium says should have been visible at that time for Apollo 12’s location:

Earth is high in the sky, but it is in fact only a couple of degrees higher than it was in the case of Apollo 11, and it does appear in a similar (and slightly higher) place in the visor compared with Aldrin’s.

Can we reasonably conclude it is Earth? Maybe.

The Stellarium figures suggest only a couple of degrees of horizontal separation between the two, so a lot depends on the influence of the visor’s curvature. In Aldrin’s famous visor shot the Earth is almost directly in line with Armstrong’s shadow, whereas here it is off to one side of Conrad’s. However, when you look at the Apollo 11 example taken side on where I suggest Earth is present, it shows a similar displacement.

We also need to bear in mind that the Earth at that time was a relatively thin crescent. We do know from Apollo 14 images, however, that a thin crescent is still very bright, and it could be argued that it is proportionately less bright in Bean’s visor compared with the other visor shots examined here.

Could it be Earth? Possibly. Is it definitely Earth? It’s not certain, it could even be sunlight flaring off some part of the LM structure, but it’s worth putting out there.

Another feature shown in an Apollo 12 visor is something that conspiracy theory morons make a lot of fuss about. The feature in question is shown in AS12-

All sorts of things have been claimed for it, usually revolving around camera gantries and lighting rigs. My view is that it’s something a little more prosaic. Below is a contrast adjusted close up of the feature, together with a section of the material surrounding the visor.

Call me old fashioned, but I don’t think the fact that when you take the feature immediately above that apparition on the visor, flip it and invert it so that it’s a mirror image, it matches very closely what we see in the visor itself.

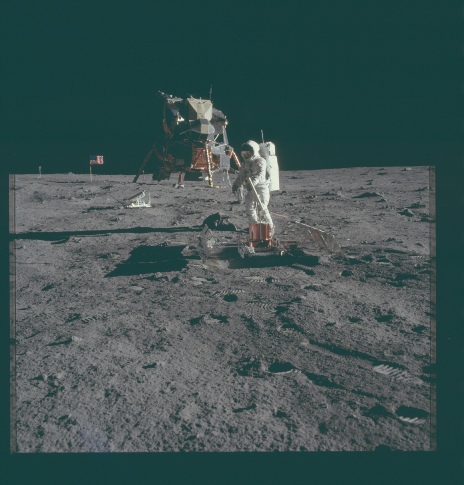

Staying with Apollo 12, it’s well know that AS12-

What isn’t so obvious is that, when you zoom in even closer, you can see Alan Bean reflected back in Conrad’s visor!

We move on now to Apollo 16.

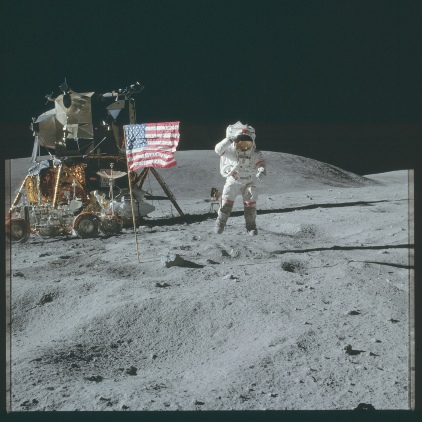

In one of the most famous pieces of Apollo TV, John Young performs a ‘jump salute’ next to the flag at the start of EVA-

In both photographs the visors show a distinct blue blob:

Experience tells us that blue blobs in visors tend to be Earth, but can we be certain that this is the case here? Time for some detective work.

Photographer Charlie Duke is standing some distance from the flag, facing the lunar module.

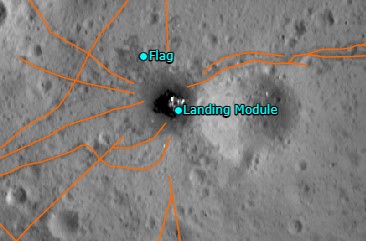

The flag, next to which Young is, erm, hovering, is north west of the site, as shown below:

Duke is therefore facing roughly south east, which means Young is looking roughly north west back at him. So where is Earth at this point?

Stellarium tells us that it is roughly north-

Looks very much as though Young is looking exactly where Earth is in relation to the lunar module, and while it is higher in the lunar sky than in other missions, the visor is curved, and that curve counts for a lot. It’s worth noting that when Duke repeats Young’s athletics his helmet is angled much more to the ground, and there is no blue dot in the visor. It is, of course, always possible that the bright dot is Jupiter -

Apollo 16 also has its debatable sights. This image (AS16-

It isn’t 100% clear, but there is a strong case for what we see there being a blue shape hanging in the sky above what could be either the flag or Jack Schmitt.

However debatable these final images are, the portrait photos of the two astronauts undoubtedly show Earth exactly where it should be in the lunar sky.

Another case of ‘blink and you’ll miss’ it comes from an Apollo 12 image, AS12-

What’s more fun is what can be seen in the visor -

Is it Jupiter? It has to be unlikely. It is certainly above the horizon, and isn’t reflecting off any of the equipment they had -

What we’re pickng out here is the small white blob next to Charlie Duke, but what is it?

It’s not Earth, that’s for certain. We can tell from the direction of the image that Duke is looking vaguely East, as shown in the image below.

In which case Young must be looking roughly west. What can we see in the west at the time the photograph was taken?

We know that Venus appeared as a relatively faint blob in colour photos, and Venus is much brighter than Jupiter. That said, what else might it be? The black and white film responded differently, so Venus’ appearance isn’t the definitive “this is how things should look”. It’s also over-

So there we have it -

Some of those interesting things demonstrate that they were exactly where they said they were: on the moon.

What you won’t see is any evidence that they weren’t -