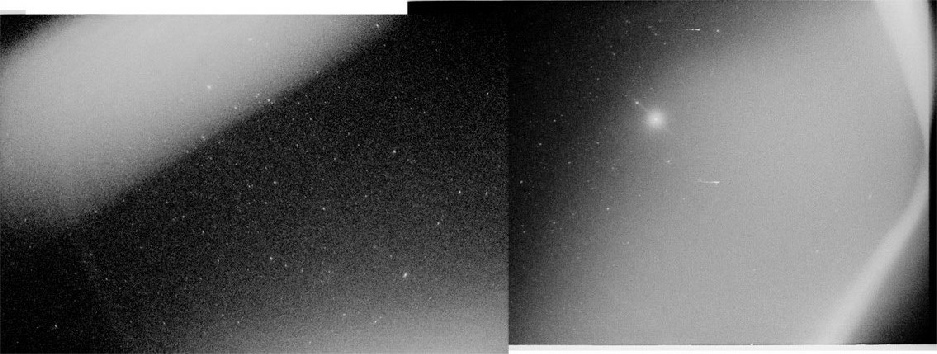

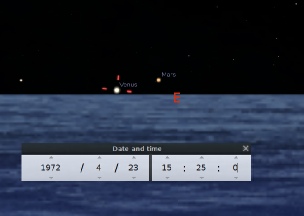

The most conspicuous feature is the extremely bright object right of centre, and it seemed highly likely on first inspection that this would be one of the planets, which for once meant that the timing of the photographs was extremely important. These timings are given in the Definitive Apollo Source Book.

The most obvious candidate for such a bright night sky object is Venus, and indeed that is exactly what it turned out to be.

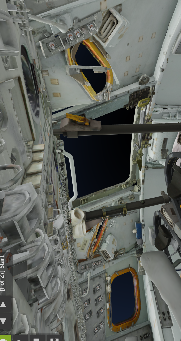

The combined view is splendid for a couple of reasons. First of all it combines Venus, Mars and, hidden in the flare near the window frame, Saturn, all taken from a point many thousands of miles from Earth. It also shows just what an incredible view the astronauts had. As long as they could get rid of ambient light, they could see the universe laid before them.

As with other pictures featuring stars, the great distances between us and them mean that it doesn’t matter whether a photograph is taken on the moon or the Earth, the star patterns are the same. However, because Mars and Venus are in the frame what we can definitively state is when it was taken.

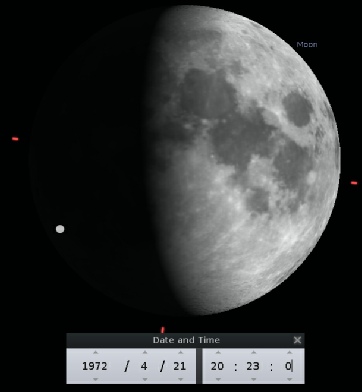

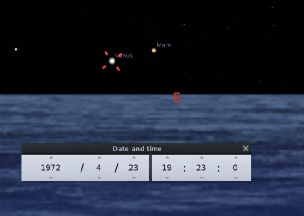

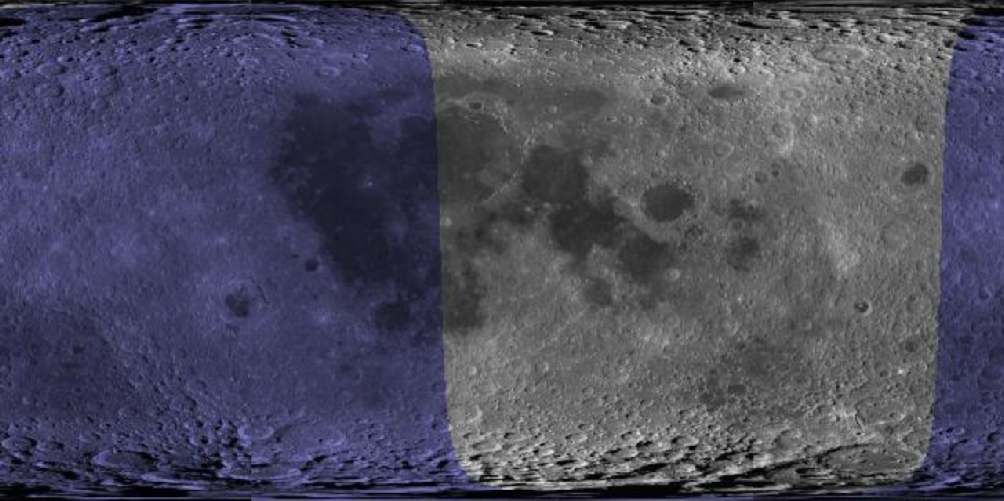

The Stellarium view above is based on a time of midnight on the 27th, and if you care to overlay the two images, you’ll find it is a reasonable estimate, which it should be given that it matches what the official reports say. Make the image 12 hours earlier or later, however, and you get the two versions of the same scene shown below.

Although there is no information as to what direction to look in, the constellation shown is very recognisable to anyone in the southern Hemisphere, the Southern Cross.

There aren’t enough stars present, or even (to be fair) enough objects that we can be sure are stars, but it is only reasonable to present everything available. Make your own mind up.

Sadly, that’s all we have for Apollo 16’s stellar photography efforts. Another magazine (126) features the results of Gegenschein photography and another batch of Gum nebula images, but as yet this is unavailable.

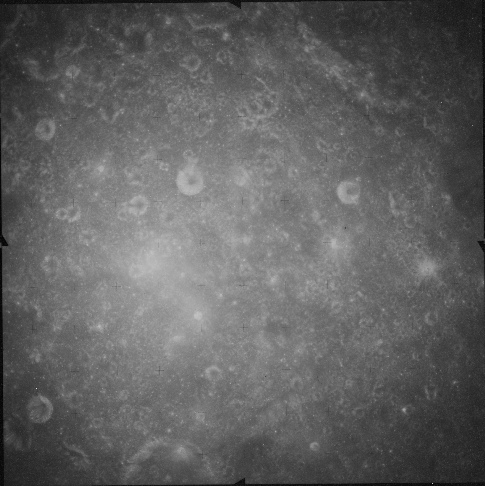

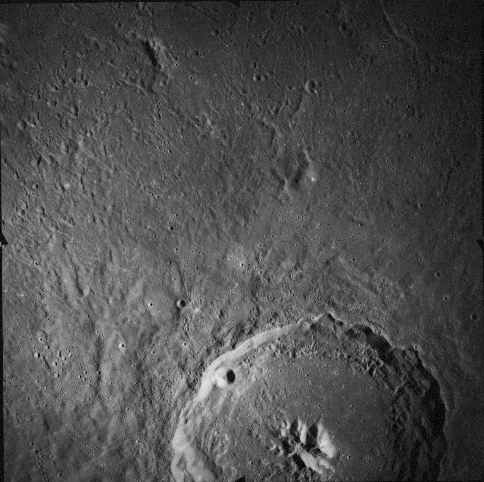

What we do have to look at are several photographs of the lunar surface taken under illumination from Earthshine, and it would be a shame not to look at them. For the uninitiated, Earthshine works in the same way as moonshine does: light reflects from the Earth’s surface and illuminates the moon. The effect can be seen around sunrise and sunset when, in the right conditions, the unlit portion of the lunar surface stands out against clearly the night sky.

The best images are on magazine 127, AS16-

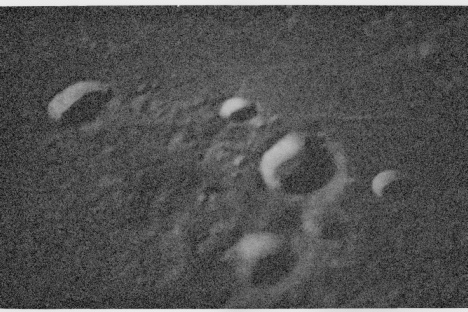

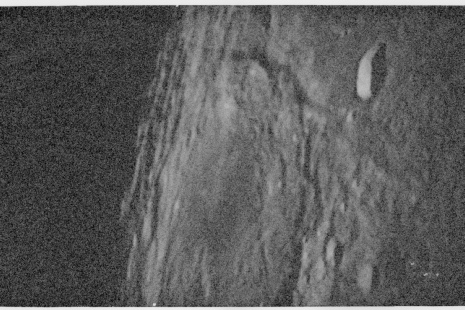

According to the reports these two photographs were taken at 20:22 and 20:24 respectively on 21/04/72 with an exposure time of 1/125 of a second. This is a remarkable shutter speed for a dark area, an is indication both of the amount of light given out by the Earth and the light capturing capability of the Zeiss lens.

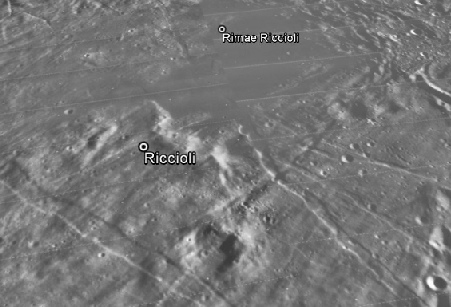

The photographs themselves are of Riccioli crater and some smaller ones to the east of it. Riccioli is a crater near the western limb, and was definitely in the dark at the time it was pictured. The images below show the Stellarium view of the moon from Earth at the time of the photographs (approximate position marked by the white dot), and a terrestrial view of the same area photographed in 2004.

A perfect match. A similar version of the image is also available in this 1974 report, where it is mistakenly inverted! The Venus image also features in the report.

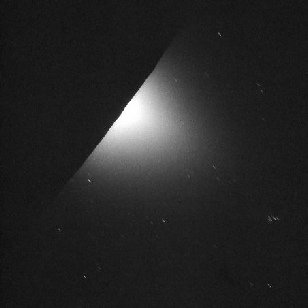

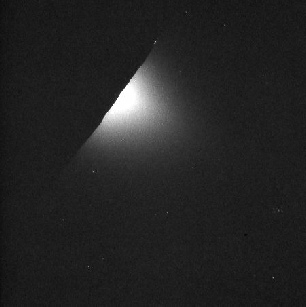

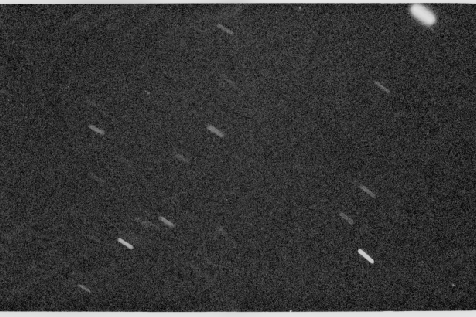

While the 35mm magazines don’t show any of the solar corona photographs, we do have some in the 70mm Hasselblad record on magazine 124. Two images sequences in this magazine show the corona and the stars around it, and the best examples of these are shown below, AS16-

The first set was taken on revolution 38 (which commenced at 147:10) and the second set on revolution 47 (started at 165:08).

What can we see on them? Well, Stellarium shows us should be visible at a midpoint in time between the two sessions (middle, above).

The cluster of stars halfway down the right hand side are the Pleiades, while on the left the bright star just below the corona is Mothallah. At the top of the photograph above the corona is Menkar.

All the stars are where they should be for the time they were photographed, in a solar corona that could not be photographed from Earth.

The only other dim light photographs currently available are in a Hasselblad magazine (magazine TT), but it is unlikely that any stars will be identified because the feature shown is likely to be light reflecting in a water dump. This is discussed in the mission report, where they mention that a water dump was photographed ‘possibly’ (according to Charlie Duke) on 70mm film. It isn’t clear when the photographs were taken. The photographs below show one of these images (AS16-

What is worth pointing out here is that while the wider view of Riccioli is very similar to that of the Earth-

The other Earthshine views are difficult to identify -

The Stellarium view taken 12 hours earlier is on the left, 12 hours later on the right and both are superimposed on the Apollo image and made slightly transparent. The Apollo image has been darkened a little to make the glare around the window less prominent. No other changes have been made,

Venus and Mars are clearly in different positions while the stars remain fixed. Saturn’s much greater distance from us means that its movement is small enough to be undetectable over this time period. An astronomer would be able to tell you more accurately, but it will be many many years either side of this date in 1972 before these three planets share this configuration in this precise position in the sky.

The photographs were taken at the time it was claimed to have been taken, and they were taken in space.

Having settled that debating point, we can move on to looking at the other CSM attitude.

The report used above also helpfully points out that Venus is in shot in some of the frames, and it can be identified flashing by in the top right corner of this sequence of images from the remainder of the Zodiacal light frames.

As in the previous example, it is evident that the stars are being photographed from a moving vehicle -

The next star photographs from Apollo 16 are to be found in magazine 129. Most of the images are identified as ‘unused frames’, but there are several that contain useful images of an experiment designed to assess the impact of spacecraft emissions (from eg gas venting, urine dumps, particles from thruster burns) on photography, with a view to working round any problems in the future Skylab missions. The photographs, taken when the crew were well on their way home between 23:24 on 26/04/72 and 00:54 on the 27th, were done in 2 attitudes.

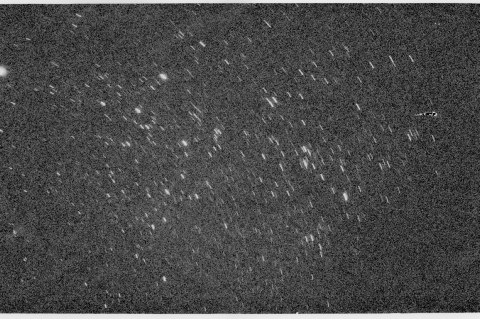

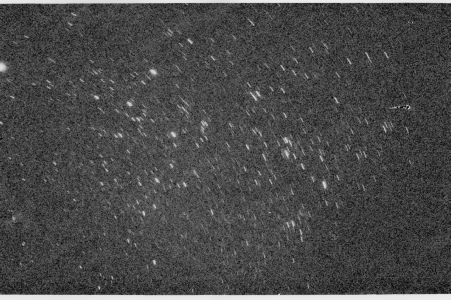

The first attitude is best illustrated by AS16-

Before seeing if we can locate what these photographs are showing, it’s worth discussing what’s in them.

Believe it or not, they all show roughly the same view. The two clearest ones on the top and bottom right show pretty much the same region of sky, and this can be determined by picking out the three stars in a line (the central one of which is Adhara) in the upper left quadrant.

These same three stars can also be seen in the bottom left image, which shows them as star trails.

Star trails are common in photographs taken from Earth thanks to its rotation under the view the camera is observing. The most spectacular images are those where the camera has centred on a pole star, around which all the stars apparently rotate from our viewpoint. The further away from the pole star, which appears as a fixed point, the more pronounced the elongation of the trail. In the northern sky this is Polaris, in the south it is Sigma Octantis.

In our photograph, we have a similar focal point that is not moving, while the other stars are shown as trails the further away they are from that point.

Is that focal point the north or south celestial pole?

Not to put too fine a point on it: No, it is some distance from it. Using Stellarium it is possible to obtain views of the sky, and we can use these as a comparison with our Apollo 16 photos to see where they actually are..

The report linked to above tells us not just when the photographs were taken, but of which part of the sky. It gives the image boundaries as between 7h35m Right Ascension (RA) and -

So there we are, Apollo 16 takes a photograph of stars, which is a big kick in the nuts for everyone who says they didn’t.

They also took it when not pointing at the celestial pole, which means that the movement in the two other photographs (taken over 4 minutes rather than 1) is from the window mounted camera rather than the stars themselves. In other words it wasn’t from a camera stuck on the ground.

The next set of star photographs in magazine 127 are listed as showing ‘Zodiacal light’. This is light from our sun scattered by cosmic dust, It is very faint and therefore difficult to photograph. A large number of frames were exposed attempting to photograph the phenomenon on 21/04/72 either side of 21:00. As with the Gum nebula photographs there is mixed quality, but it is possible to make out some clear star patterns. The best views are in AS16-

First of all let’s see where 20004 is. The report above gives co-

If we look around that area we indeed find a match:

Apollo 16 Low light & Surface photography

Like the previous missions, Apollo 16’s low light level photography had several aims.

Photographs were to be taken of the Gum nebula, of Gegenschein regions, of the lunar surface under Earthshine, and to see what influence venting from spacecraft had on the quality of photographs in preparation for the future Skylab mission.

A number of magazines were exposed with the camera either hand held or secured on a bracket in the window behind a specially rigged blind. Cabin lights were usually turned off to minimise ambient light intrusion. Command Module pilot Mattingly stated in the mission report that he turned off all the lights even when not required to just to be on the safe side. CSM rotation was also minimised,

Magazines 128 and 130 were used for calibration purposes and are not available online. Magazines 127 and 129 are available here. Magazine 126 is yet to be found. Most of the images were taken using a Nikon F, but some were taken using the Hasselblads. The 16mm DAC was also used, but magazine HH has not been found online yet.

This report contains details of what can be found in the magazines, and the preliminary science report discusses the experiments. More information can be found in this report and the mission report.

What can we see in them? The frames in the report linked to above are discussed in reverse order, and we’ll stick with that to make life simpler.

The first batch of images are of the Gum nebula. This nebula is a diffuse structure occupying a large amount of the southern sky and emits very little light, making it hard to study from Earth. Using a range of filters and exposure times, the region was photographed on 21/04/72 and around 18:45 GMT while the spacecraft was on the lunar far side. The frames covering this period are AS16-

And here is Venus, marked by the red cross hairs, compared with AS16-

It’s debatable, but it is in the right place.

And now for something completely different.

Venus gets mentioned a lot in the above because as one of the brightest objects it is easy to find. As it turns out, that brightness and its position in the lunar sky meant that it also cropped up in three Apollo 16 images taken from the surface.

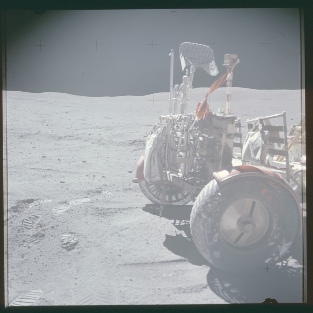

The work of GoneToPlaid found that it does appear in three separate images in magazine 117. That magazine was exposed during EVA-

The ocean landscape has been chosen purely to make it easier to find Venus. Notice the location of the planet over there just north of East.

The three photographs in which Venus can be found are AS16-

And here is the planet from each one:

Now, it’s not unusual for Apollo images to show all kinds of blobs and scratches, but a blob appearing in the same location in the sky is strongly suggestive that it isn’t some sort of image defect or bit of dust on the lens.

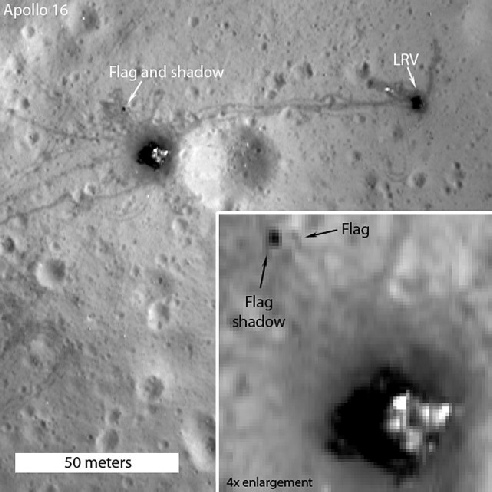

So, how can we be sure it’s Venus? Well for one thing it’s about at the right sort of angle above the horizon. For another the three images are all looking in the right direction. The first two images in the sequence of three show the lunar module with the flag on the left. As can be seen below in the LRO view of the site, the flag is to the north of the LM, so the photographer must be stood to the west of it.

Even more careful examination of the photographs showing the lunar module reveal that the photographer is south of a position parallel with the westernmost lander leg. The direction in which the photographer is looking is absolutely consistent with the location of Venus in the sky.

Could the astronauts have spotted it? Possible, but unlikely. The photographs show that they are looking in the same direction as the sun on a bright lunar surface. Photographs of the astronauts taken at the same time show them with their gold sun visors down. As Charlie Duke remarked in his autobiography:

“Though the sun was shining brightly, the lunar sky was pitch black; no stars were visible due to the bright reflection off the lunar surface.”

Luckily the cameras had other ideas.

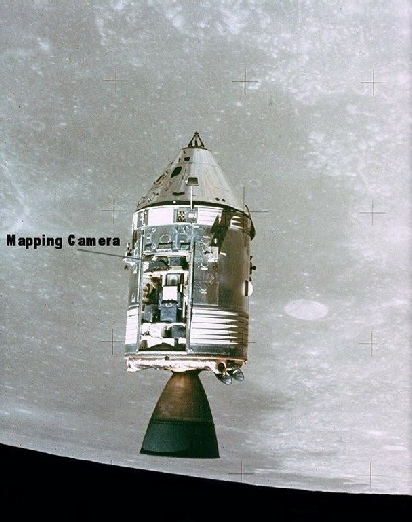

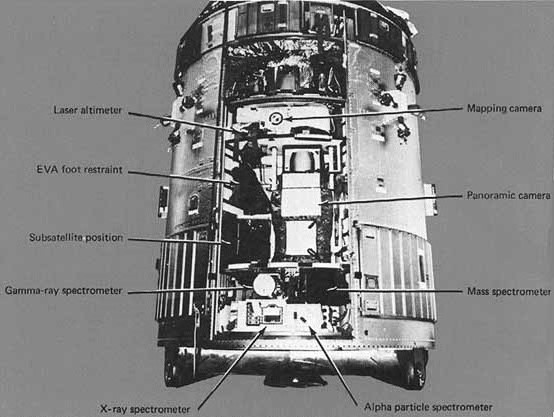

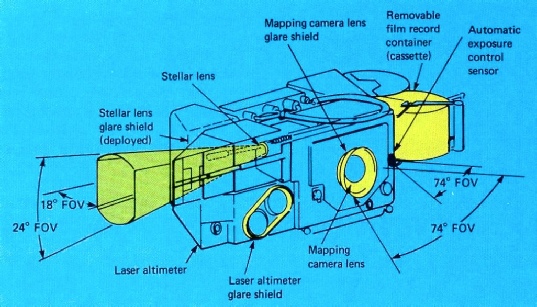

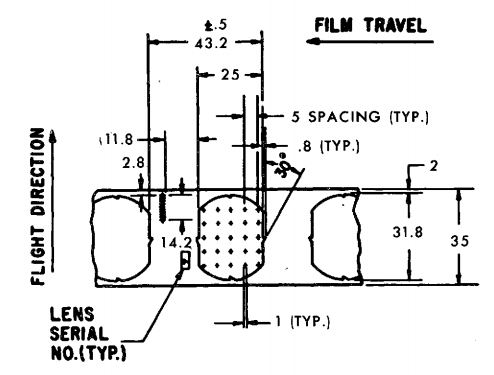

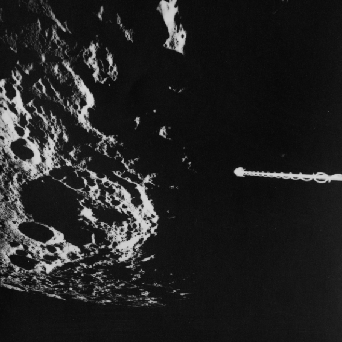

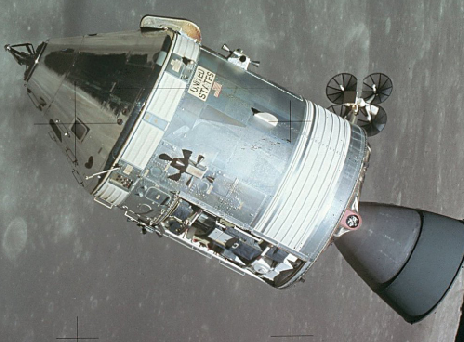

Another area of stellar photography that has not been possible to explore is that of the stellar mapping camera used in the Metric Mapping Camera system employed on Apollos 15 to 17. The stellar camera was used to provide a way of locating the Apollo Command and Service Module in space in combination with a laser altimeter. It’s show in the images below, courtesy of this page.

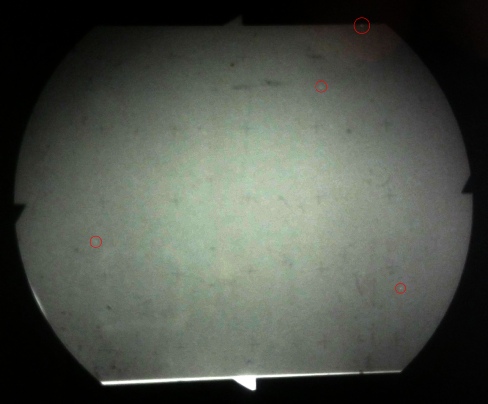

The idea is that as the main camera scans the ground, the stellar camera is angled to the skies to capture stars. The stars in the stellar images are used, together with laser altimetry, to give a precise indication of the angle of the camera imaging the ground, which helps to determine any distortion in the field of view if it deviates away from perfectly vertical. This article gives a good description of how it worked, and this one shows the nature of the film:

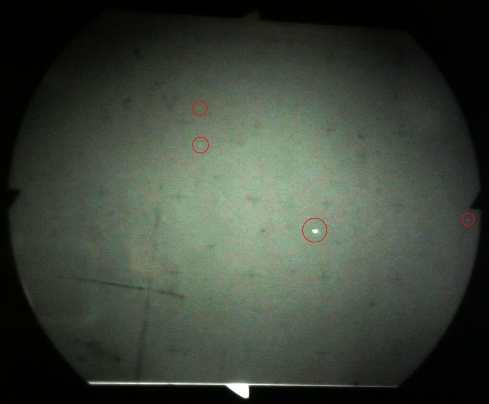

And here are the same two images contrast adjusted and with bright objects highlighted.

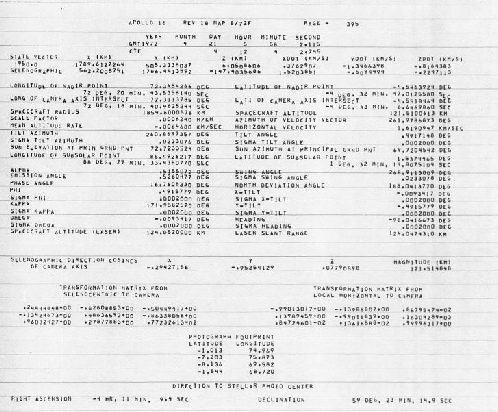

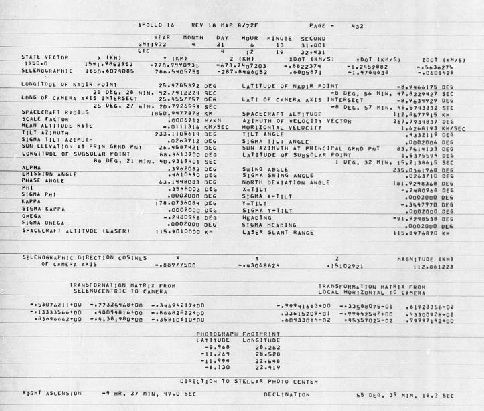

So what are they showing? Well, to try and work that out we need to know where we’re looking. Thankfully we have some clues from this 1.4 Gb document, and from the images taken by the main camera. The document lists the state vector data for the photography, in other words where the CSM was in space and the location of the images it took.

After initially thinking that the stellar frame numbers were equivalent to the mapping image numbers and putting the relevant images on rev 25, this document tells us that the correct mapping images are 79 frames less than the stellar image count, so they are image and 395 and 432 respectively. The numbers in the images above match up with images taken revolution 18, taken at 05:58 and 06:13 on 21/04/72.

Here are the two images.

And here are the state vector data:

The MMC images themselves show that the main camera is pretty much vertical. The nose first direction of travel means that the stellar camera would be pointing roughly NNE.

Can we work out from this what the two stellar photographs are showing? The data in the state vector document give a direction to the stellar camera centre. Sadly, these aren’t that helpful, as it isn’t clear whether the coordinates it gives are based on the moon, the position of the observer, or from Earth. The declination values are positive which indicates that we are looking towards the north, but the negative right ascension values are not ones usually used (these are normally given in a 24 hour clock system).

We can be reasonably sure that the bright layer at the bottom of the image is that of the lunar horizon,but what the bright objects are is much less clear. It may be that the very obvious bright object in image 432 is Polaris, but it’s not certain. It’s also possible that it is nothing of the sort, and that everything I’ve highlighted is just a fault on the image, but nonetheless they are there. Hopefully one day better quality versions will emerge.

For the final part of Apollo 16 we look at a relatively new source recently uploaded to the ‘Archive.org’ site, namely two magazines of 16mm film used during the dim light and solar corona imagery.

The magzines are ‘HH’ and ‘MM’, and are listed in the photography index as being high speed film. This is the link to the footage.

Looking at the flight plan and transcripts for Apollo 16, it becomes clear that magazine HH was used during the same solar corona photography sessions as magazine S for the Hasselblads. There are very few shots that show anything clearly in magazine HH, but several sequences do show this pattern.

The images from this camera are no doubt buried in a long forgotten archive somewhere having served their purpose, but a request to the data collection organiser for NASA did turn up a couple of low resolution second or third generation copies from the Apollo 16, namely these two:

That’s it for the visible spectrum, but meanwhile on the lunar surface they were setting up a telescope to look at stars in the far ultra-

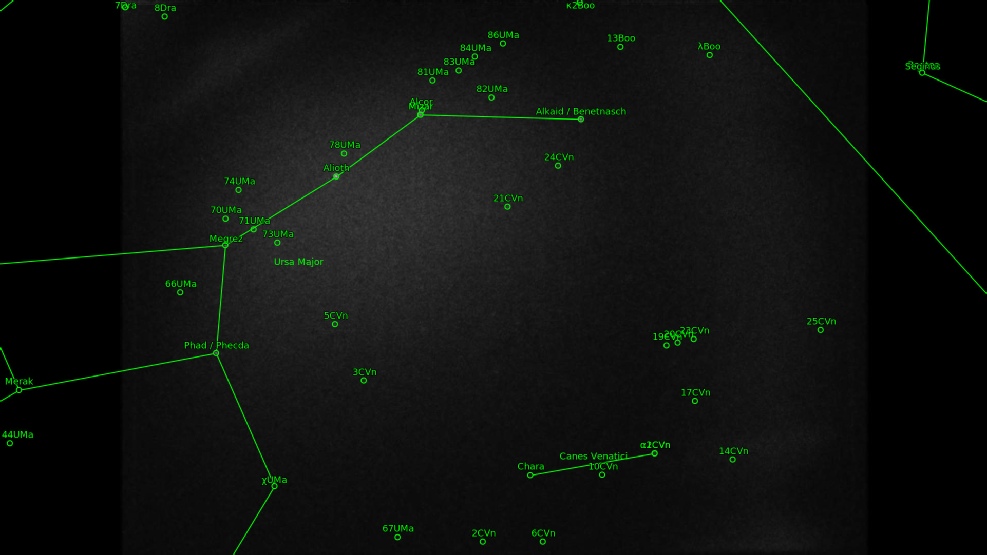

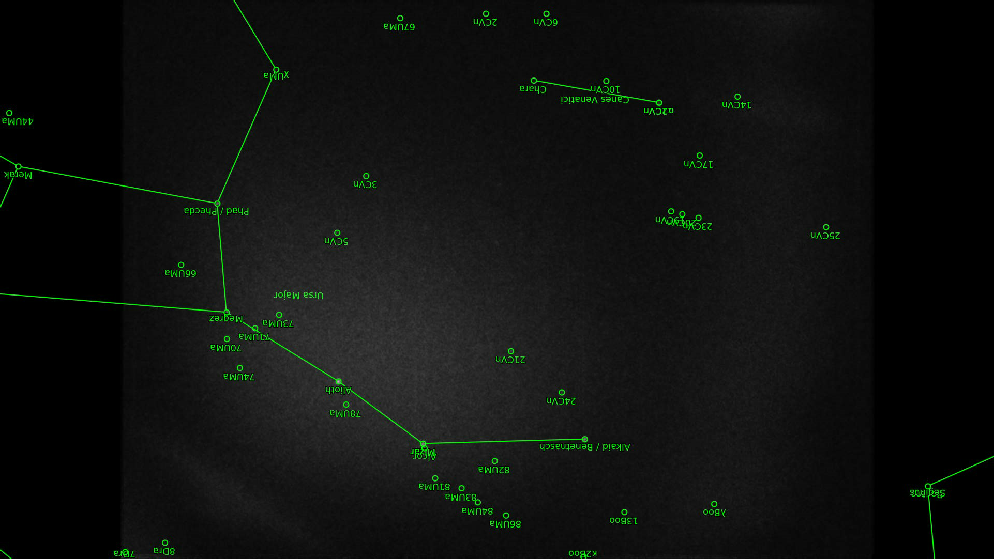

Anything that shows up consistently in obviously different shots is a candidate for further study, so I submitted the to astrometry.net for analysis, and it returned this:

The constellation it is picking out is Ursa Major, but anyone who knows the night sky will spot that it is the wrong way round. The key to explaining this feature is that the DAC was mounted so that it looked into a mirror to film outside so that flipping the image gives the same, but now astronomically accurate, result.

You’ll see why I’ve oriented it ‘upside down’ shortly. The next thing to work out is whether the crew would have seen this. We know that one window was looking forward to the sunrise, which at the time of the first solar corona session was on the lunar far side:

At the time, and location, Stellarium shows us this view:

Ursa Major is over there on the right. At the time this photograph was taken the CSM was also taking Mapping Camera images, which means that it was oriented with the SIM bay pointing downwards but at an angle. The presence of the dipole antenna in the images from this revolution shows that the CSM was travelling nose first:

The DAC camera would have been mounted in the window to the right of the hatch, which would therefore have been pointing towards the northern sky and this in the perfect position to capture Ursa Major while other windows captured the approaching sunrise.

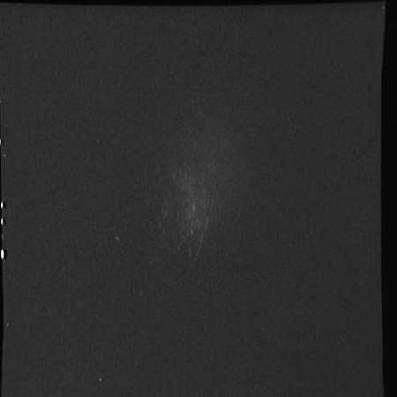

Magazine MM is a somewhat trickier proposition, given that it’s only ‘official’ mention in the mission flight plans and transcripts is in reference to the Skylab contamination photography at the very end of the mission. Truth be told there is very little that stands out in the magazine that can be definitively identified as a stellar view, but there are these stills:

On the face of it there isn’t much to go on, but if the various frames are stacked (a photographic technique combining multiple frames to produce a single clear image, we get the following.

Even more careful examination shows that this sequence is showing exactly the same stars as the sequence from magazine HH: Ursa Major, this time with an added bright bloom.

My suggestion, and I am happy to be proven wrong, is that as they were the same film type, magazines HH and MM were used interchangeably, and this sequence showing Ursa Major was probably done on the next sequence of solar corona shots. The bright bloom is likely to be from the lunar surface.