4.10.3 Apollo 7

Apollo 7 is often argued to have ended the flying careers of the three astronauts who crewed it. Walter Schirra, Donn Eisele & Walter Cunningham manned an occasionally tetchy mission, disagreeing with the ground on a number of occasions over procedural matters, disagreements compounded by illness and tiredness. Despite this the mission was actually a technical success in that it achieved all the things it set out to achieve, and while the complaints and very public spats were well reported, most of the mission went well and there are numerous good-

Schirra went through many of the reasons for his more contentious decisions during the mission, including the cancellation of a TV broadcast. He gave TV a low priority during the mission, regarding it as a potentially dangerous distraction: while broadcasting and filming the crew were paying attention to the camera and not the spacecraft!

Apollo 7 was launched at 15:02 GMT 11/10/68, and returned to Earth on 22/10/68, and during its 11 days in orbit tested life support systems and docking procedures, as well as the ability of three people to live in a confined space for extended periods (many readers of the mission transcript will find amusement in descriptions of the practicalities of urination and bowel movements in orbit!). The mission timeline can be found here.

In terms of photography, the aims were the same as previous missions in terms of photographing Earth surface features and weather formations for comparison with ground and aircraft based observations. The general mission report can be found here, and the report covering the photography in depth can be found here.

In total 533 photographs were taken on 9 magazines of film, low quality versions of which can be found here: AIA. The crew also made the first TV broadcasts from space, providing TV viewers with the first live images of planet Earth. These broadcasts do not seem to be readily available in their original form, but footage taken by the mission can be found in the NASA film ‘Flight of Apollo 7’, which can be downloaded here: archive.org.

The ESSA satellite images covering the mission period can be found here, and the ATS ones here. There are several additional images covering the mission dates in this publication: Applications of Satellite Meteorology, that are of better quality than the ESSA mosaics. We also have the benefit of another ESSA World publication (found here ESSA World) that deals specifically with the weather aspects of the mission. The article expands on the edition referred to in Chapter 2, and describes the work of the Spaceflight Meteorology Group with specific reference to Apollo 7 from the preparation of the launch vehicle to the choice of landing areas. This article has good quality ESSA and ATS views of two hurricanes photographed during the mission.

It also describes how astronauts would be briefed on global conditions so that they would be familiar with the types of weather formation over which they would be flying. It becomes clear from reading it that there were many agencies involved in preparing meteorological data for a variety of purposes, all of whom needed to co-

As with the missions described earlier, the photography report does a more than adequate job of describing the features visible from orbit, and there is little to be gained from reproducing it fully here.

What we will attempt to do here is follow the timeline and mission transcripts (available here), picking out references as appropriate and seeing if photographs can be identified, then compared with the satellite record. One feature of this (and other LEO missions) that can be observed in the transcripts is a telling indicator that lunar bound crews could not possibly have been in LEO ‘pretending’ to be somewhere else.

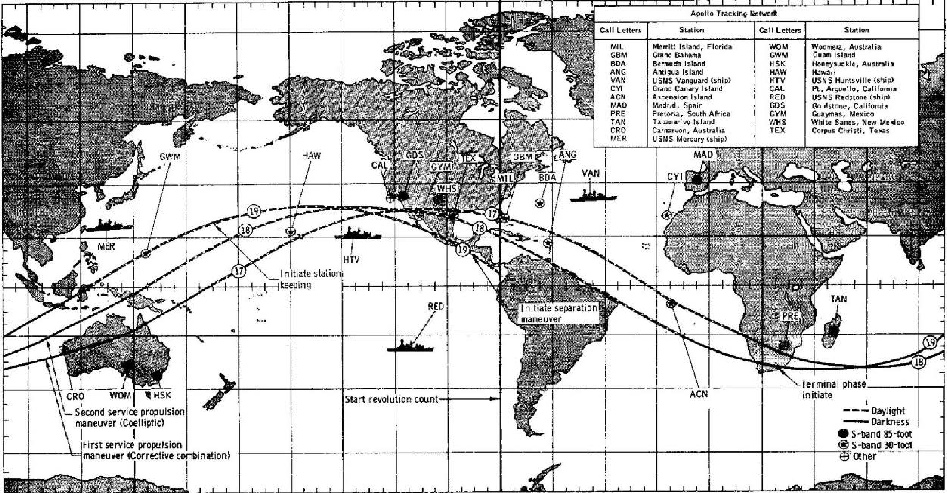

These low orbit missions are moving at 17000 miles an hour, and consequently require a huge number of tracking stations to keep voice communications relayed successfully. Figure 4.10.32 shows the orbital path of Apollo 7 and also lists the various tracking stations involved. The mission transcripts are littered with notifications of impending communications hand overs and acquisitions, and there are breaks in communications where the on-

These gaps in communications also necessitate regular downloading of mission data for analysis on the ground.

Contrast this with the much less frequent changes in tracking stations required by moon-

It’s also probable that these rapid handovers between ground stations (sometimes as little as a few minutes were spent on any given receiver) caused some of the communication problems that added to the occasional frustrations of the crew – requests to repeat a message are much more frequent in Apollo 7 than in the lunar landing/orbit missions.

Now to explore the transcripts. We have two approaches to follow here – firstly, to identify a specific feature on specific photographs identifiable in the text, and secondly to use those photographs as markers to pick out images with more distinctive cloud formations on them. The former is complicated slightly by errors in the transcripts (eg magazine ‘S’ is occasionally written as ‘F’), and by the crews miscalculating the frame numbers of the magazines. This was probably caused in part by occasional jams in the camera mechanism, but is also from simple miscounting of the number of photographs they had taken. Magazine S, for example, is described as having many more photographs than were actually developed, and the frame number identified by the crew to Capcom often does not match the frame count of the developed photographs. Despite this, it is possible to work out from their descriptions which photographs are being discussed, and the photographic report does list the photographs and their timings.

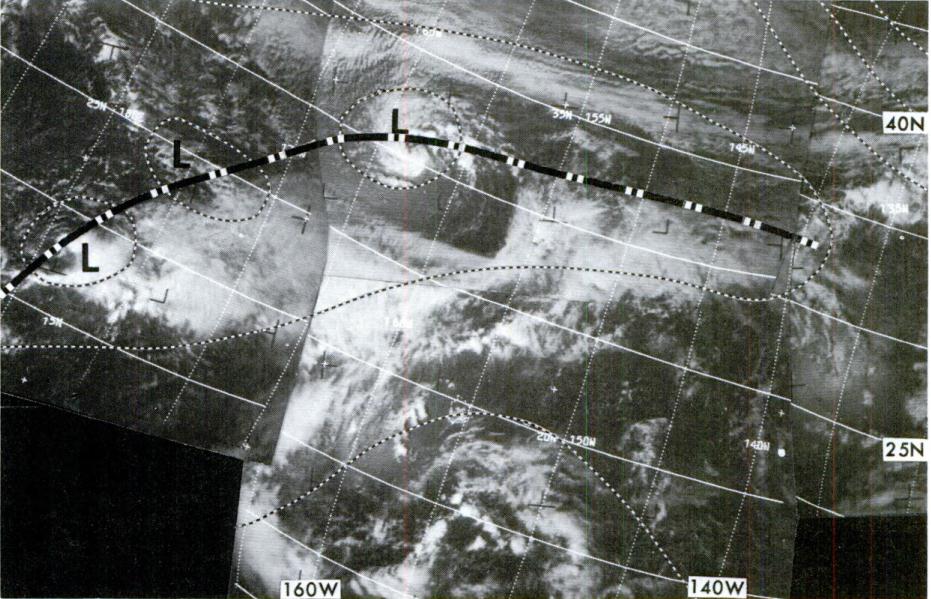

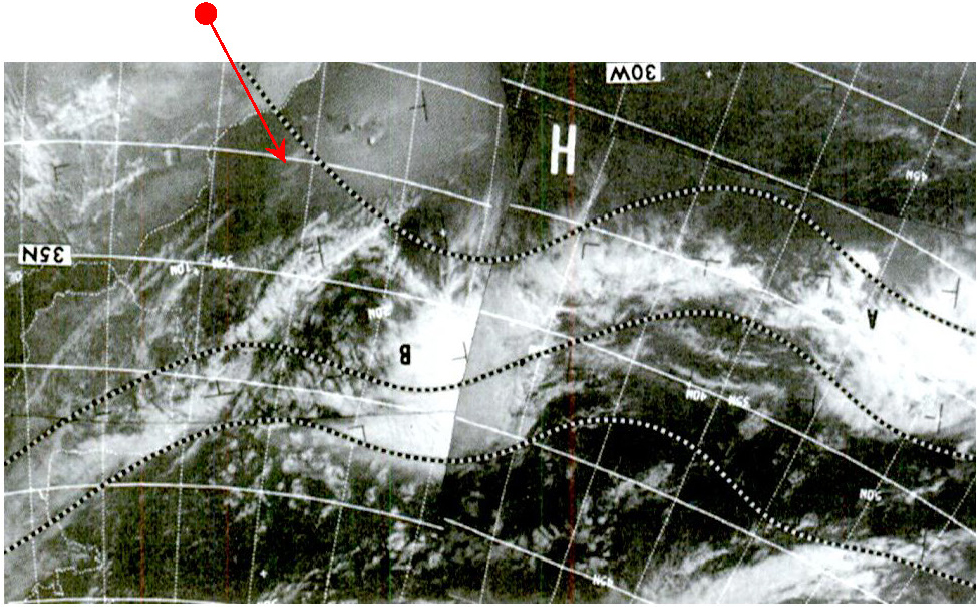

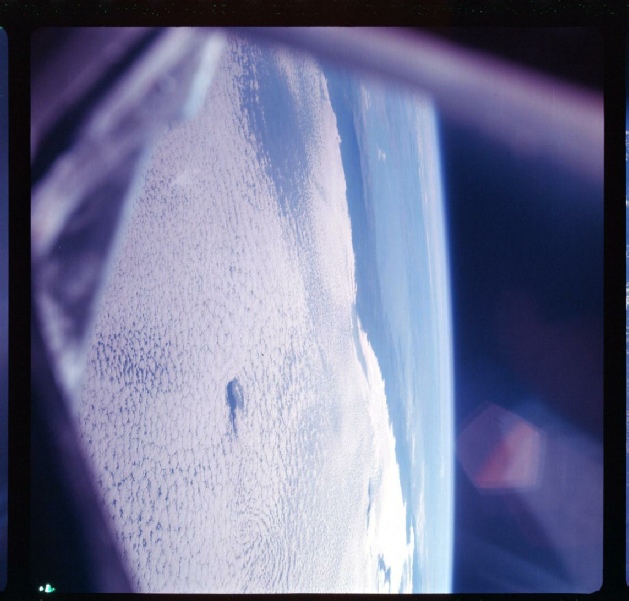

One of the first magazines used (M) contains a photograph of a weather system that is also featured in the Applications of Satellite Meteorology document, and occurs early on in the mission. The image in question is shown overleaf in figure 4.10.33. The ASM document identifies this as a low pressure trough in the mid-

Figure 4.10.33: AMS image from 10-

The image that seems to match this quite well is AS07-

Figure 4.10.34: GAP scan of AS07-

The central whirl of cloud in the preceding figures is so clear it needs no illustration with arrows, but it is worth noting that the satellite image from figure 4.10.29 was taken some 21 hours before the Apollo image. The satellite photograph in the ESSA data catalogue from the 11th was taken some 4 hours later and is show below in figure 4.10.35, along with the ATS-

Figure 4.10.35: ESSA (left) and ATS-

The detail is much less clear, but the overall storm structure is still evident, and the two central spots of cloud are well defined.

On the following day, the crew begin a sequence of images starting over Hawaii (although not actually featuring Hawaii), and ending in the region of the Bahamas. There are two parts of this sequence that can be picked out from the satellite record, the first at the coast where Apollo 7 picks out an area of cloud, and the second in the centre of the north American continent where there is a small area of distinctively shaped cloud in an otherwise cloud free zone.

The end of the sequence is announced at 18:15 GMT on the 12th, and is identified as being on Magazine P. The frame numbers are not given, but 3 hours before that a picture of the end of the Florida canal north of Tampa (labelled in the transcript as a breakwater at Tallahassee), and this is AS07-

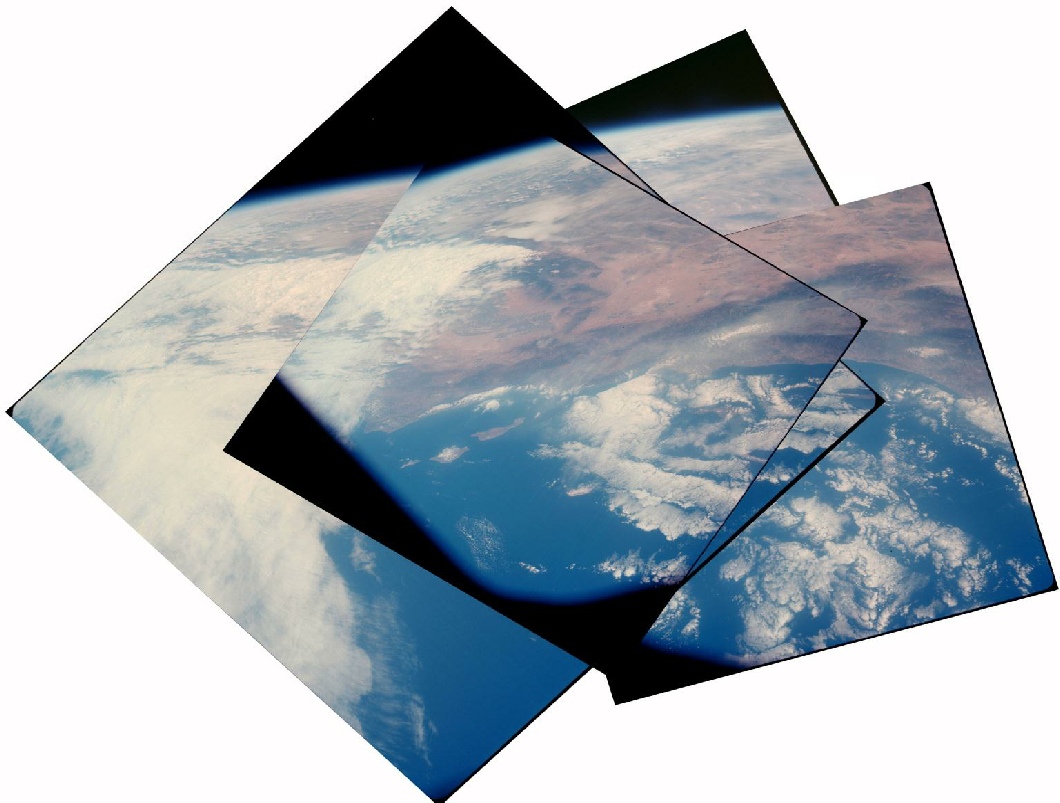

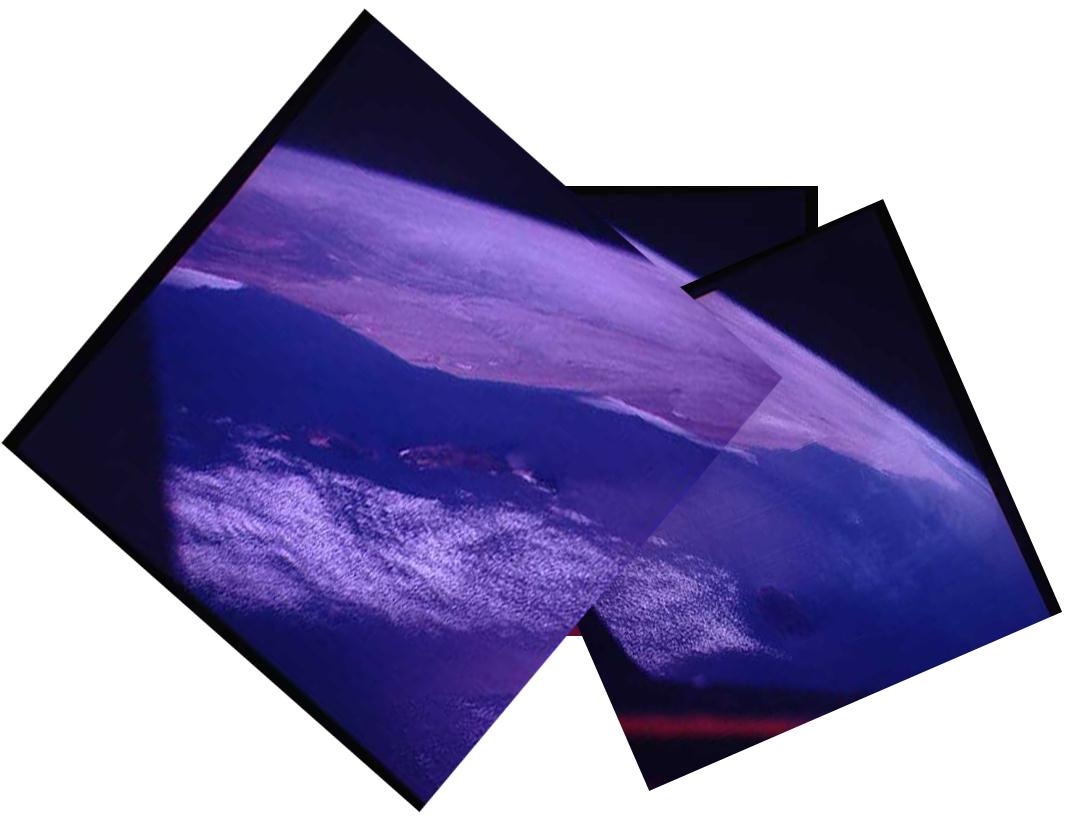

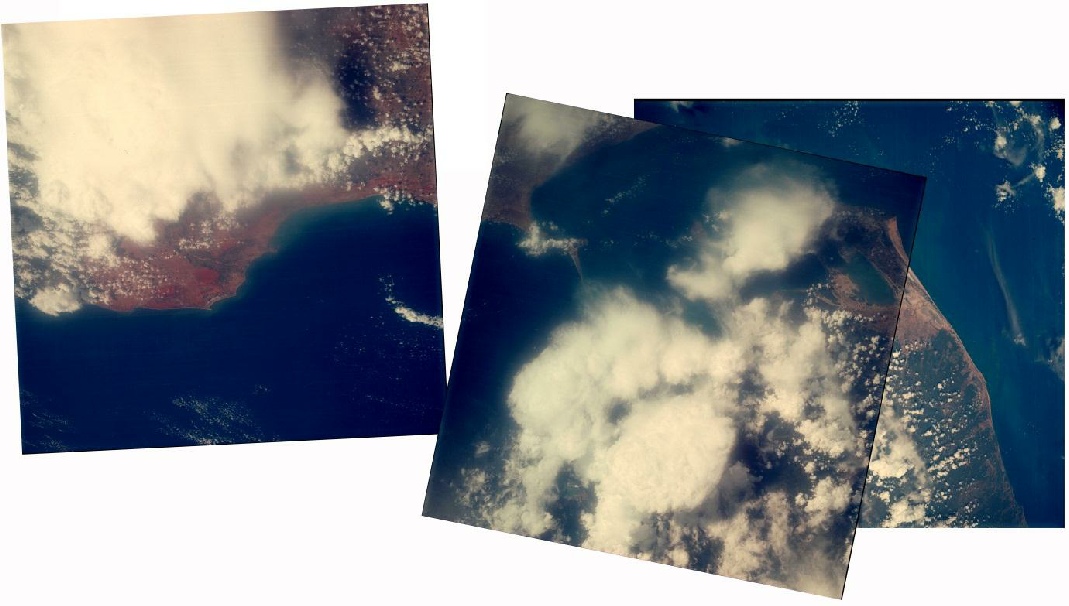

It is possible to combine several images together to produce a more complete image of the west coast than can be shown by a single image, and this is shown over the page in figure 4.10.36. The corresponding portion of the ESSA mosaic is shown in figure 4.10.37.

Figure 4.10.36: Montage of AS07-

Figure 4.10.37: ESSA image from 12/10/68. The red dot marks the position of Los Angeles.

The long band of cloud stretching onshore from the Pacific is very obvious in the satellite picture, although the other less substantial cloud masses are not as easily made out. The satellite pass for the ESSA image would have been 00:05 on the 13th, around 6 hours after the pass by Apollo 7. It should again be obvious from the photomontage in figure 4.10.29 that despite using 4 photographs, the portion of the Earth visible is still extremely small, covering a swathe around 500 miles wide. The difference between a fixed camera position used for the preceding unmanned missions and the obviously human hand should also be clear.

In the same pass over the USA, another image is captured that shows a distinctive cloud feature – can this be identified on the satellite image? The photograph (shown below in figure 4.10.38) is recorded by the GAP as being over Llano Estacado in Texas, and the photograph below has been oriented to match (roughly) the correct orientation based on features visible on the ground. The local time of the photograph is recorded as around 11:30 am, and close examination of the ground under the clouds shows the well-

Figure 4.10.38: AS07-

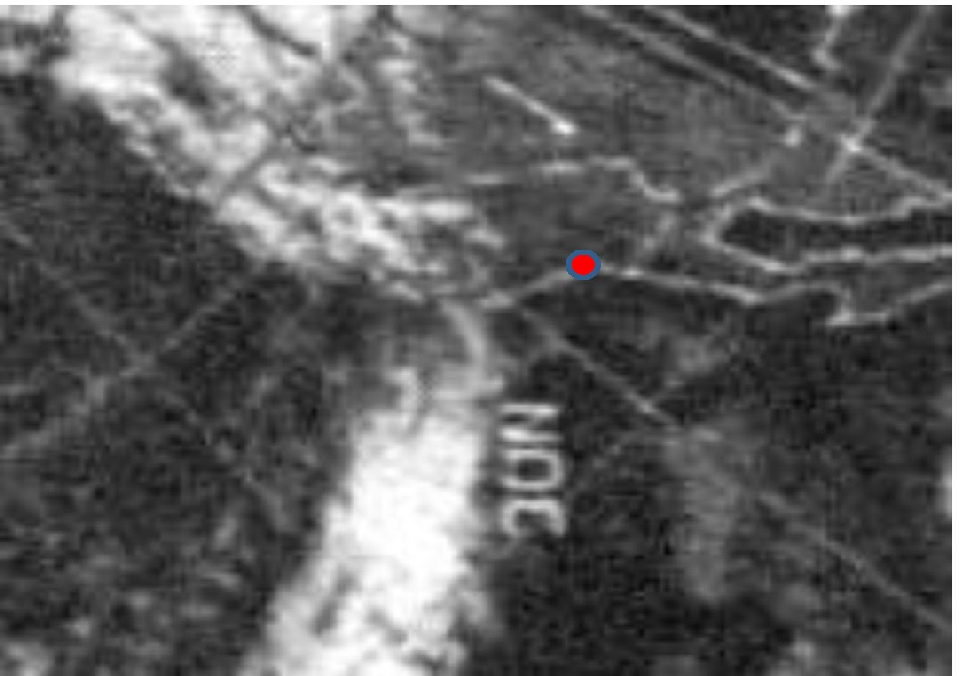

The corresponding part of the ESSA mosaic is shown below in figure 4.10.39, the bulk of which shows the state of Texas. The pointed end of the cloud pattern in question is almost exactly in the centre of the image, exactly where the photograph says it should be.

Figure 4.10.39: ESSA mosaic dated 12/10/68 showing Texas in the centre.

Again it should be obvious that the photograph, despite the oblique viewing angle, shows a much smaller area than the photographs examined in preceding sections, and any image showing a whole Earth image is absolutely not going to be in LEO.

Most of the photographs taken over the next couple of days are of landscapes free from cloud or of weather patterns too faint to be visible on the ESSA mosaics in use here. One day’s data (from the 14th) is missing from the ESSA photomosaic data completely but there is one image shown in the ASM document off the Canary Isles. The image is recorded as being taken in two passes between 15:00 and 16:50 GMT. These are not the times recorded for the appropriate passes in the data collection, so it is likely to be from a different ESSA satellite. It is given in figure 4.10.40.

The area covered by the satellite data is shown in AS07-

Figure 4.10.40: ESSA image from 14/10/68, rotated to match the orientation of figure 4.10.35. Possible light cloud indicated by red arrow.

Figure 4.10.41: Photomontage of AS07-

Figure 4.10.42: ESSA image from 12/10/68 compared with AS07-

The answer to this apparent discrepancy is obviously the time gap between them and the nature of the clouds involved. The sequence of photographs taken on the 14th are specifically recorded in the transcript at 10:56 on the 14th, around 5 hours before the coastal part of the ESSA pictures, which would be plenty of time for the coastal cloud to disperse and the light cloud off Lanzarote to move on. The time gap between the ESSA 7 image on the 12th is similar, with the Apollo image recorded as being taken at 11:08 in the photography report, 6 hours before the ESSA photograph but in this case the coastal cloud has persisted. {Photographs AS07-

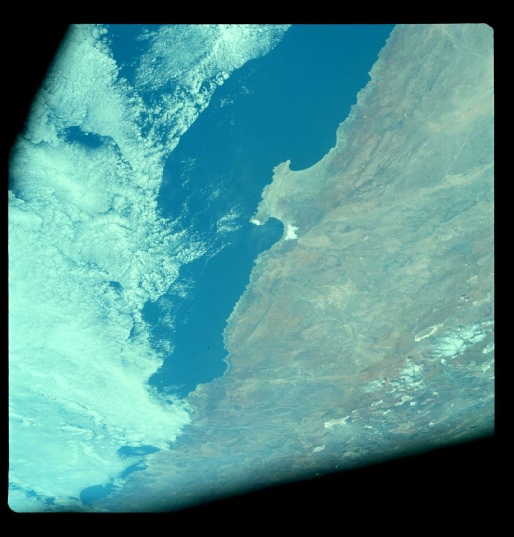

Another nice coastal image is AS07-

Figure 4.10.43: GAP copy of AS07-

.

It is just possible to determine from the ESSA image the clear area to the south of the Apollo photograph, the coastal bank of cloud, and the thin fingers of cloud extending southwards from the top of the photograph.

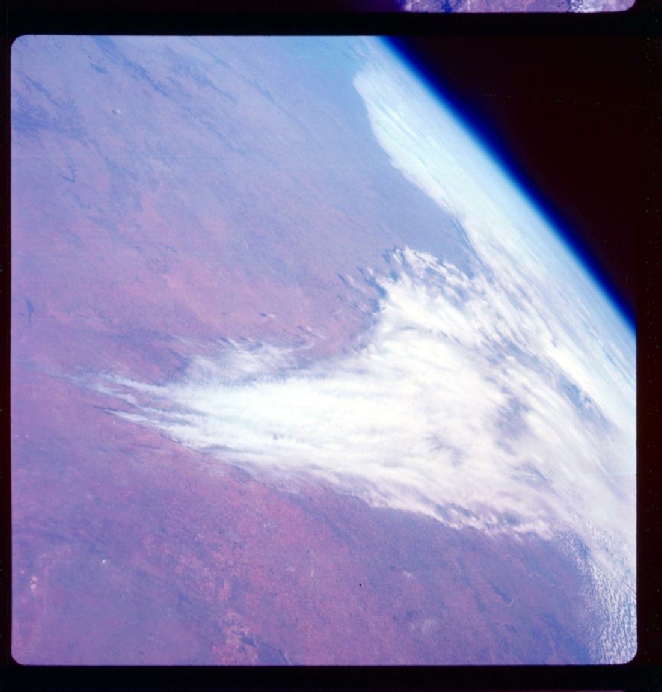

A short while later, Apollo 7 flew over the Indian sub-

Figure 4.10.44: Photomontage of AS07-

As with all ESSA mosaic images of this region, the image dated 15/10/68 was actually taken on the 16th at 08:05, 32 minutes before the Apollo photograph (as recorded in the CM transcript). The cloud over southern India and the north-

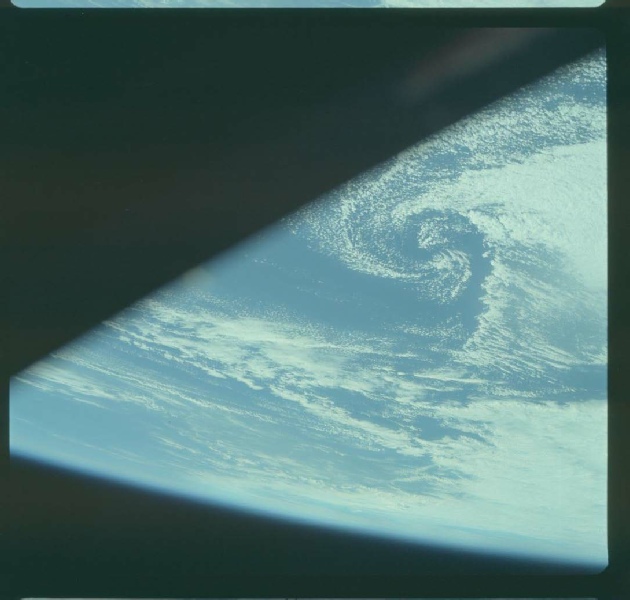

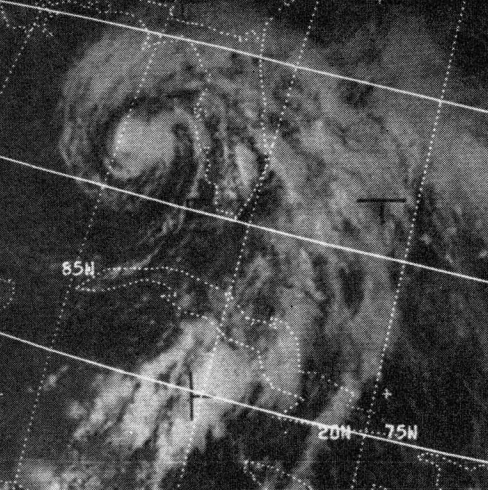

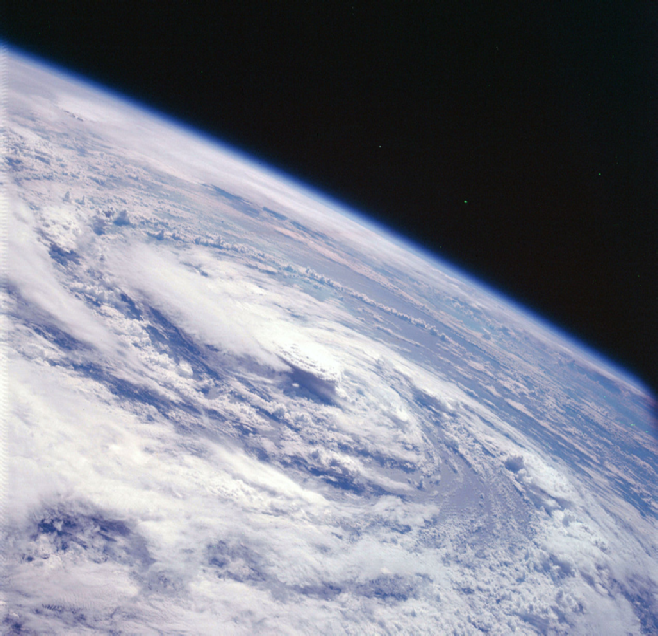

Magazine S ends with the most famous photograph from the mission, AS07-

AS07-

Figure 4.10.45: GAP scan of AS07-

Figure 4.10.46: GAP scan of AS07-

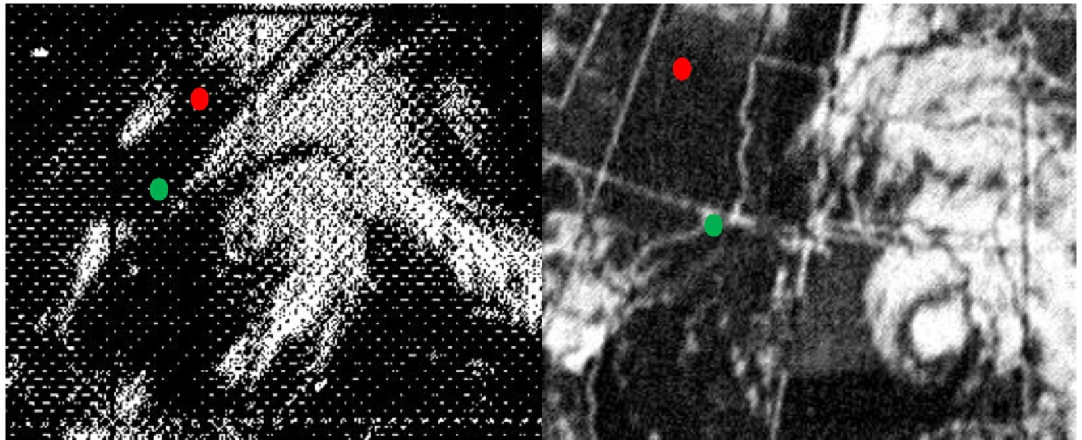

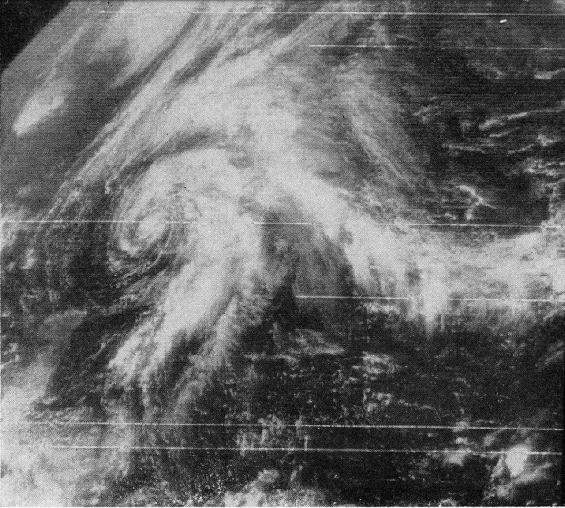

Figure 4.10.47: ATS (left) and ESSA (right) images of the Gulf and Hurricane Gladys from different sources. On the upper images, the red dot identifies Fort Worth, the green dot Galveston.

Left is AS07-

The last images in the magazine are, as mentioned above, discussed in many reports scholarly and otherwise, with good reason. The mission is the first to view tropical storms in such detail with from space, and the eye of a hurricane was marked for the first time by an overflying spacecraft. The usefulness of the space observation was not lost on the general public – one newspaper report (read out to the crew) describes them as a “manned weather satellite” under the headline "Big storm tracked by Apollo 7".

Comparisons of satellite, radar and Apollo images of the hurricane are made in this journal article: Journal of Applied Meteorology, which describes the event as the first time all these tools had been used to examine a hurricane, and .discusses photogrammetric techniques used on the Apollo image to determine the locations of key elements of the hurricane structure and explore the 3-

The Apollo mission report described the photographs taken of Gladys as

“the best colour photographs of a tropical storm circulation taken from space”

observing that the Apollo photographs are better than the black and white ESSA image as

“colour photograph enables the meteorologist to ascertain more accurately the types of cloud involved”

After the shots of the hurricane, the crew do record many more images as being taken on magazine S, but they are either mistakenly attributed, or there was a malfunction. Either way there are no more from that magazine publicly available.

The next magazine utilised in photographic work is ‘R’, and there is an interesting remark made during its use. At 166:37 GET, or 12:39 on the 18th, Schirra says that

“We can see all the launch pads and it looks like she’s ready for business.”

after which Eisele says

“We can see Saturn V on the pad”.

This obviously begs an interesting question: Could they have seen a Saturn V on the pad?

The Saturn in question would have been the Apollo 8 launch vehicle. This left the assembly building on 09/10/68, and is pictured en route to pad 39A in figure 4.10.48.

Figure 4.10.48: Apollo 8 on the way to the pad 39A. Source: NASA

The Saturn was definitely in place when the crew made their statement. This ESSA News article notes that ESSA’s weather forecasts were critical in making a decision as to whether the Apollo 8 vessel should be returned to the safety of the hangar as Gladys approached on October 16th.

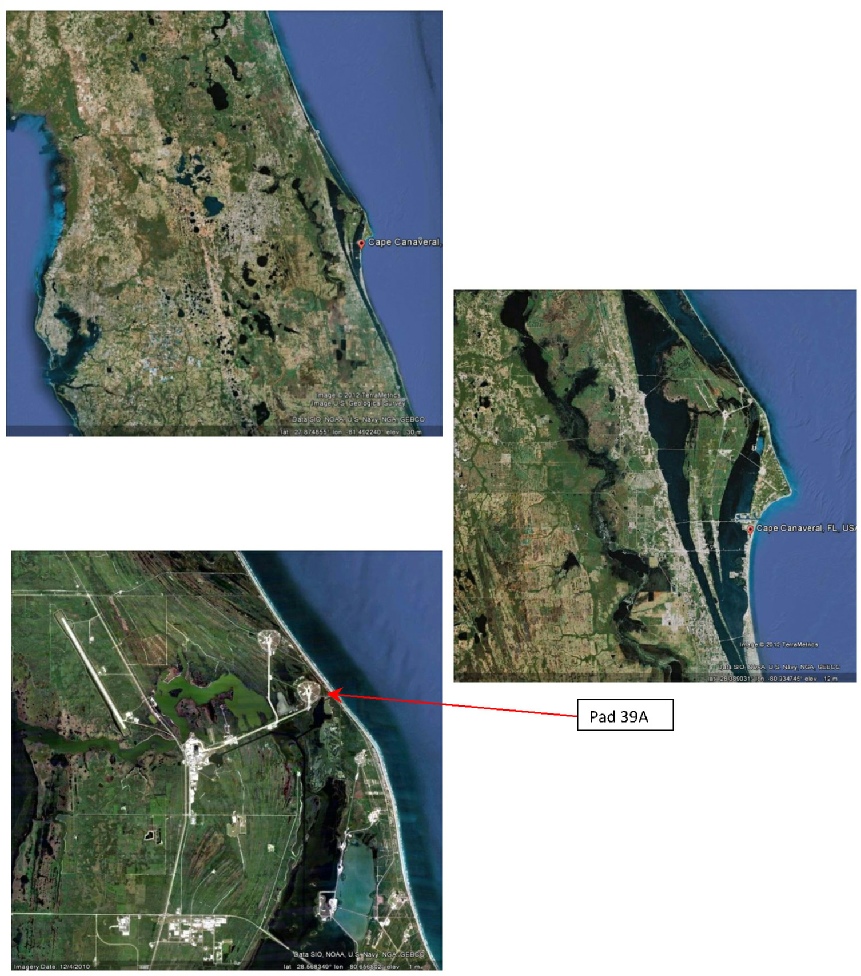

Having established that Apollo 8 was present when the observation was made, the next step is to see whether it was visible from Apollo 7. So that we can work out what we are looking for, figure 4.10.49 shows the view of Pad 39 in Google Earth, both from a distance and in close up.

Figure 4.10.49: Google Earth views at varying distance of The Apollo launch pads.

The Apollo 7 crew did take a photograph at the same time as mentioning the Saturn on the pad. A few moments before their comment, they record photographing the eye of Hurricane Gladys (AS07-

Figure 4.10.50: AS07-

To be fair, it is difficult to tell whether there is indeed a Saturn on the pad, but it is equally difficult to tell if there isn’t! What is clear is that they could indeed see the launch complex on that day and at that time. There are other photographs with good views of the Cape, and perhaps the most spectacular are two of the SIV-

Figure 4.10.51: AS07-

AS07-

Figure 4.10.52: Apollo launch pads seen in AS07-

One continent so far missing is that of Australia. The crew did take several sets of images of Australia, sometimes trying to capture the Carnarvon and Honeysuckle receiving stations as they passed over. Most of these photographs show no or very little cloud, but one image of central Australia shows an apparently considerable band that ought to be easier to pick out on the satellite image.

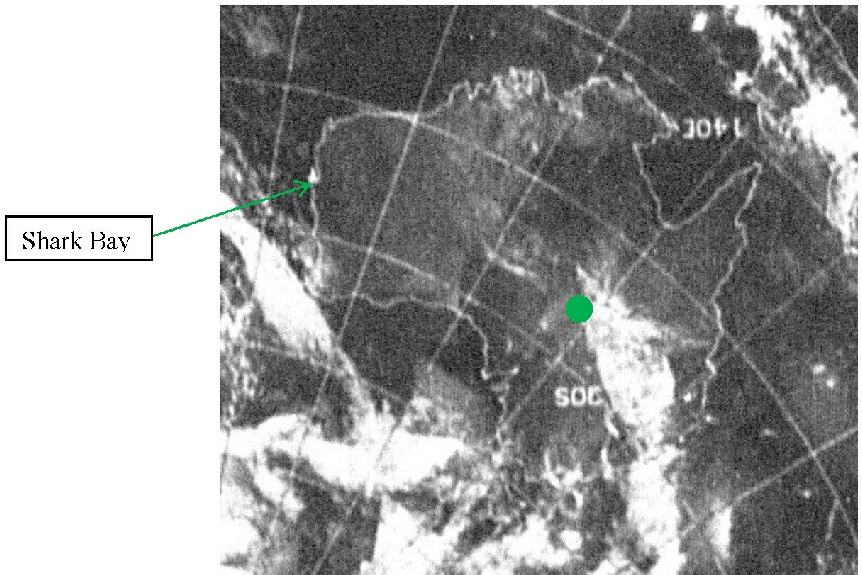

The picture in question is AS07-

Figure 4.10.53: GAP scan of AS07-

The photography report states that this image was taken at 183:45 MET, or around 06:45 on the 19th. We can also check the mission transcripts, which specifically mention the photographs of the Nile that are next in the magazine as being taken just over an hour later.

The photograph itself centres on a feature visible on the south-

Just for completeness, the ESSA mosaic pass, while dated the 18th , was actually carried out at 05:04 on the 19th.

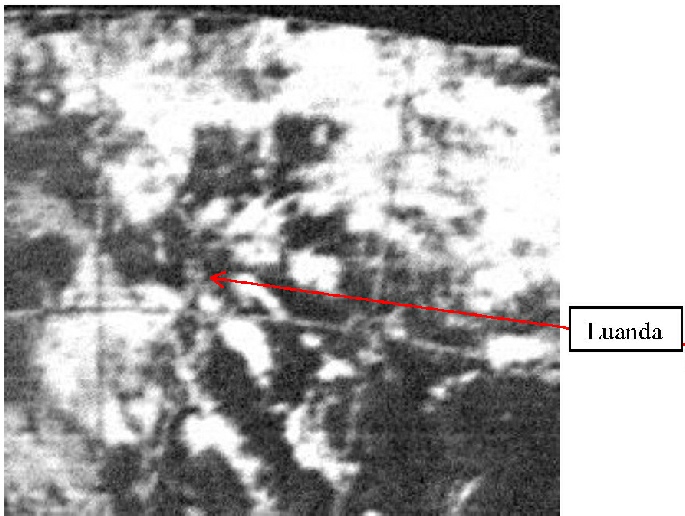

Later on in the magazine, we have another good set of clouds that are recorded in the transcript as just the African coast, but in the GAP and the photography report as being Luanda, on the coast of Angola. The image in question has to be AS07-

Figure 4.10.54: GAP scan of AS07-

Once again we have, despite a low resolution and poor quality image, a satellite mosaic that still manages to be consistent with an Apollo photograph, with the coastal city visible on both pictures surround by patchy cloud. On the preceding day the ESSA image shows the area to be covered with cloud, and on the following day it is completely clear. Track 1 on the 19th was commenced at 15:09,. Compared with the Apollo 7 photograph’s recorded time of 12:39.

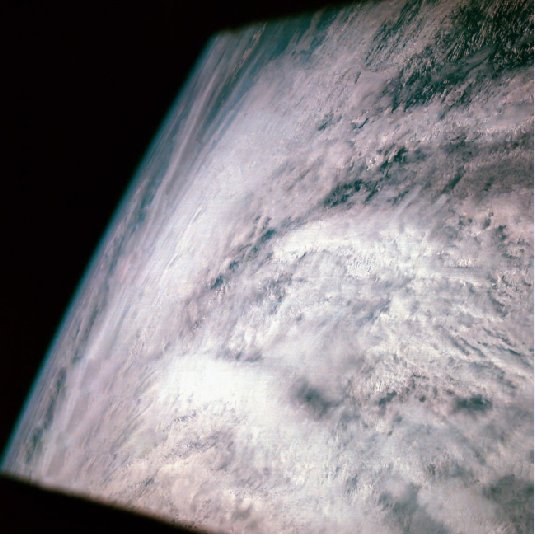

Magazine R continues to be the magazine of choice for the next day or so, capturing as they travel what the mission report describes as

“one of the best views from space of the eye of a tropical storm”

in the form of AS07-

One of the best shots of cloud formations off the west coast of the USA comes in the form of AS07-

Figure 4.10.55: GAP scan of AS07-

The satellite image shows complete correspondence with the Apollo image. The spacecraft is above the large mass of cloud to the left of centre looking towards the relatively clear Gulf (there is a suggestion of hazy cloud), beyond which is the American Continent with more substantial cloud in the distance. Should anyone care to check the records either side of this image, they will find that clear skies prevail off the coast of North America, and once again this can be the only day on which the photograph could have been taken.

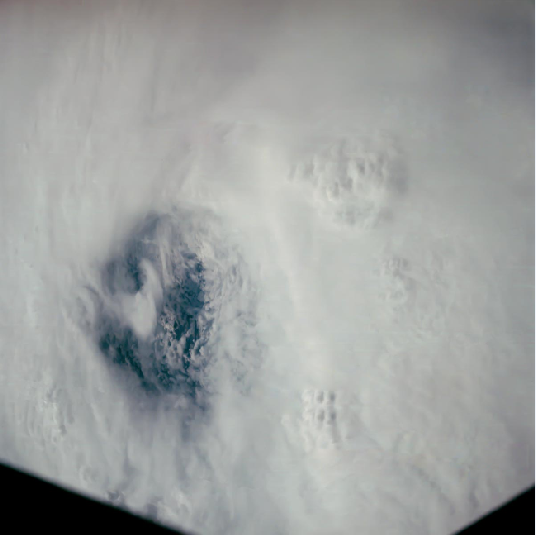

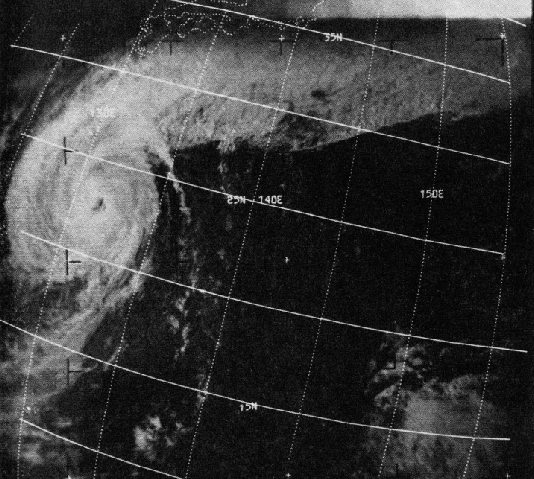

About 12 hours after these images were taken we have photographs of another tropical storm, Typhoon Gloria. Two images were taken showing the centre eye and some of the surrounding wall of cloud, ut they aren’t zoomed out enough to confirm the details in the available ESSA image. Figure 4.10.56 shows the images.

Figure 4.10.57: GAP scan of AS07-

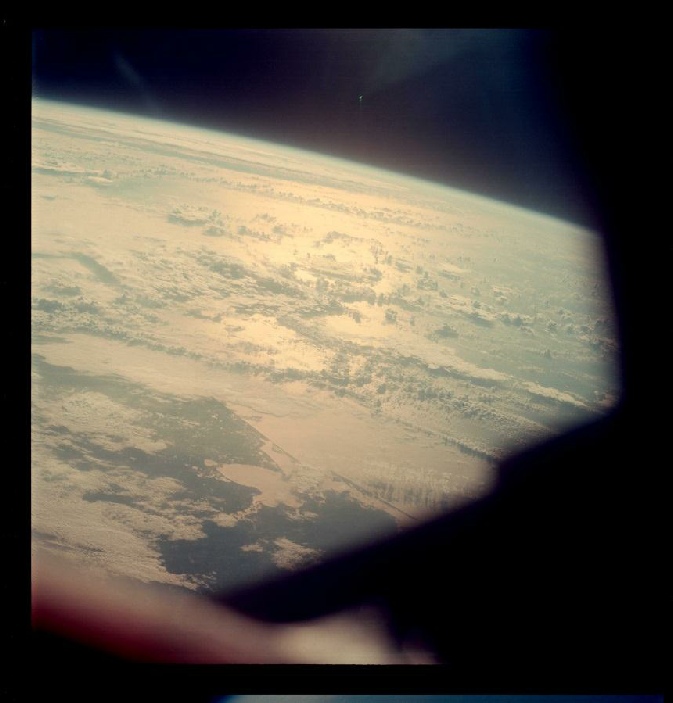

Slightly less than 16 hours after this photograph was taken, Apollo 7 began re-

It is a shame that the video footage obtained during the mission is not well categorised in terms of when they were taken, as these do contain many beautiful sequences showing some nice weather patterns. However, without clear indications of when they were taken it is considered to be a pointless and overly time-

For the final part of the mission other magazines are used with black and white film, but many of the photographs that are recorded as being taken are not available at the AIA, and the ones that do exist are blurred and indistinct – insufficient detail can be derived from them to determine their location. We are therefore left with colour images taken on magazine N, which returns into use in the final part of the mission.

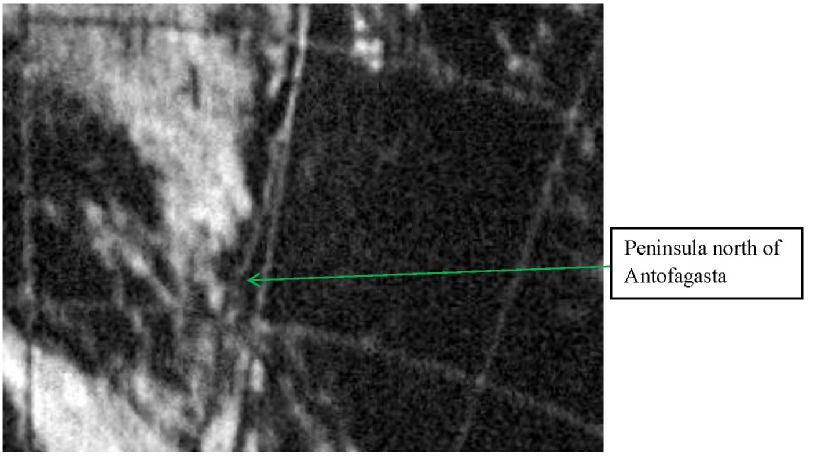

Of those taken, the best one available for the purposes of this report is AS07-

The ESSA section of the photomosaic was commenced at 18:04 on that date. The location of the distinctive coastal feature clear of cloud above centre in the Apollo photograph is shown by the green arrow. In both figures, the peninsula is clear and has an arc of cloud offshore, which curves round to meet the shoreline further south. Another clear match between the two.

Figure 4.10.56: AS07-

Figure 4.10.32: ESSA view of re-