4.5.7 -

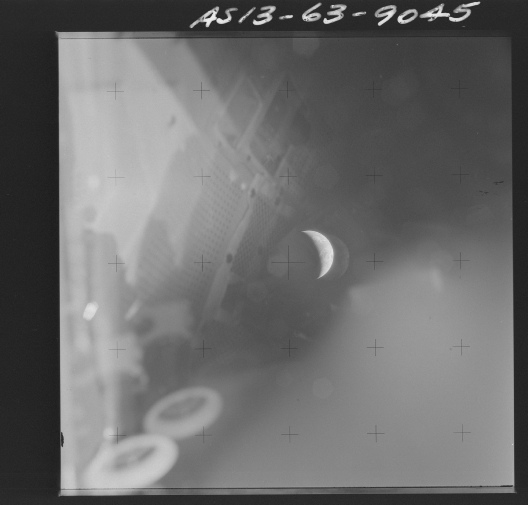

The next photograph is one that only emerged recently after an enquiry on collectspace.com, where contributor LM-

LM-

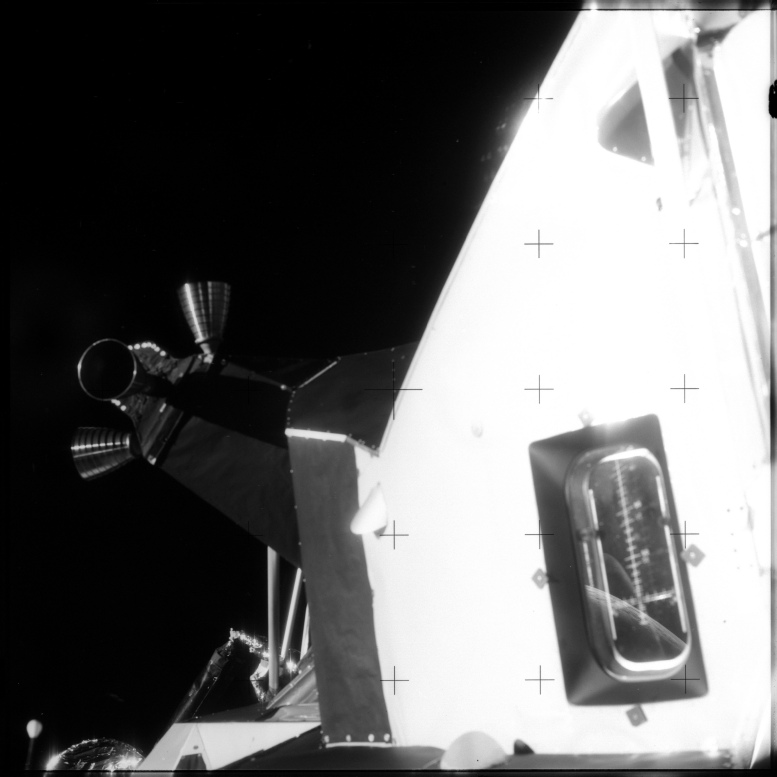

. Close examination of the photographs revealed that they were all of the same view taken with different exposure settings. One of these photographs is shown below in figure 4.5.7.1. Alongside the image is a mock up of a lunar module interior, in which can be seen the panel and equipment details shown reflected in the window through which Earth has been photographed. The simulator view has been rotated to match the view seen in the Apollo image.

Figure 4.5.7.1: Left -

Before dealing with the view of Earth, it’s worth pointing out that there are clear shots of the interior of the lunar module in the Apollo 13 photograph. I’m sure someone idiot will point out that the other photograph I’ve used is a simulator blah blah that’s how they did it drone drone, but what they have to then get around is the fact that there is a large planet Earth in the picture. Speaking of which, let’s have a look at what we can see on it, and when it might have been taken.

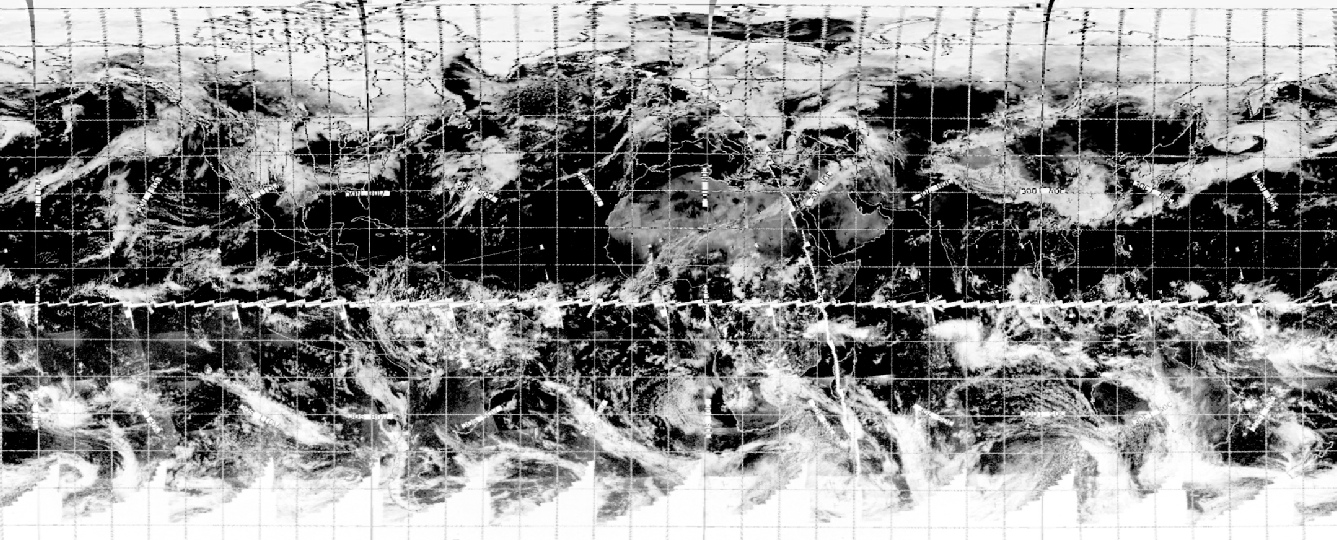

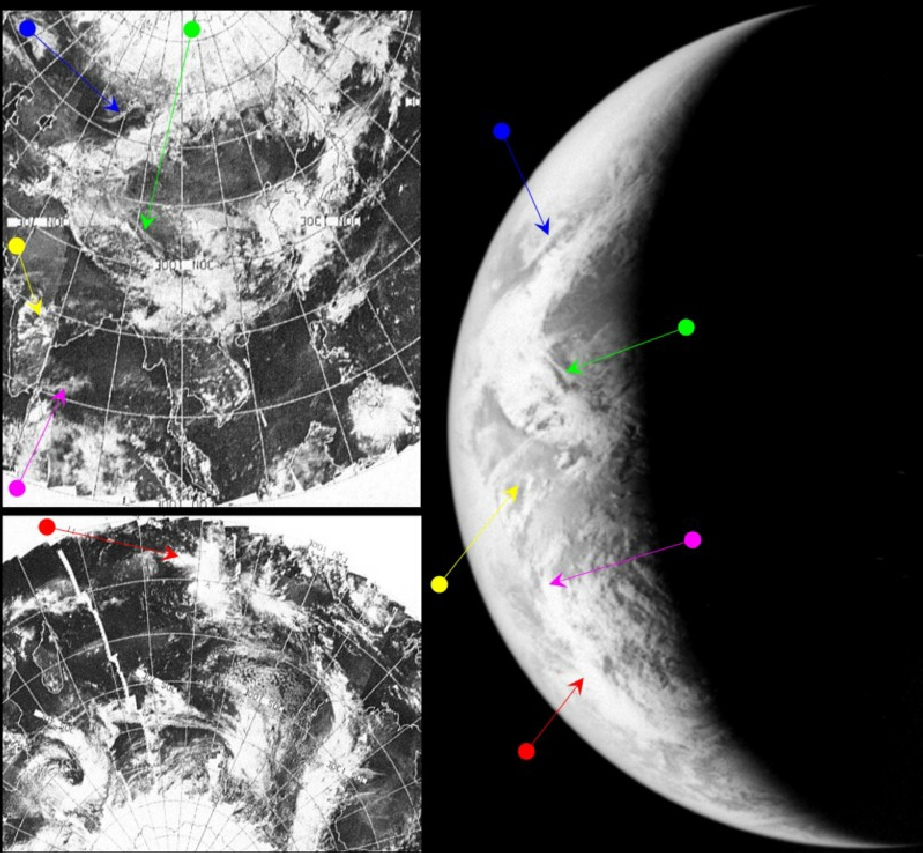

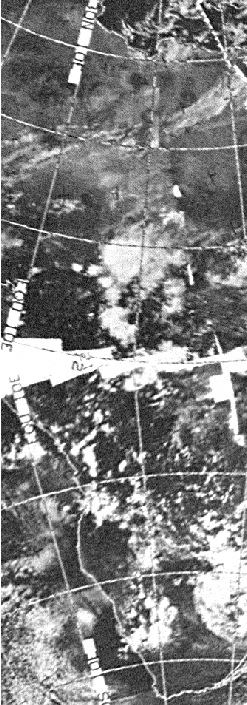

The shape of the crescent suggests very strongly that it belongs in the closing stages of the mission, so the search began on ESSA images from that part. The weather systems we are looking for turned up on the satellite view taken on the 16th, and this is shown below with a rotated and cleaned up version of the Apollo 13 photograph in figure 4.5.7.1.

Figure 4.5.7.2: Zoomed and cropped version of AS13-

The first point of identification was the ‘y’ shaped system identified in the red arrow, only faintly visible on the Apollo view, but once that was spotted the rest fell in to place. The key to the time is the system shown by the magenta arrow on the east coast of Australia, placing the time at around 06:30 on the 17th.

There isn’t much confirmation of this in the mission transcript -

We do get a small clue that confirms that Australia should be in shot at the time I suggest it was taken. About an hour after Stellarium’s time capcom tell them that they will shortly be handing over to Honeysuckle Creek on Australia’s east coast -

It’s are remarkable testament to the consistency of the Apollo record that a photograph that very few people even know exist, and equally few people have seen, can reveal details that match what should be visible. Yet another one in the eye for Apollo deniers.

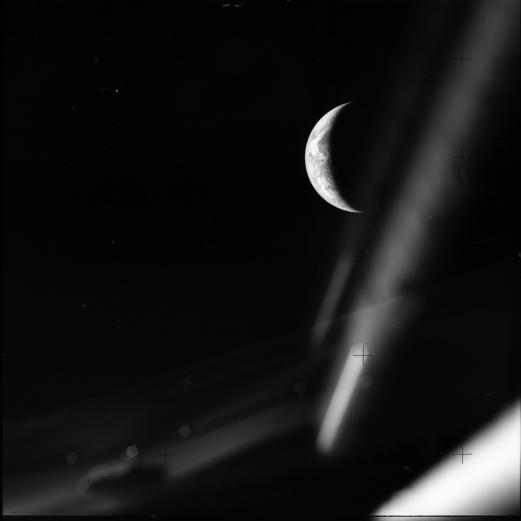

The final image in this sequence is from a so far unused magazine, AS13-

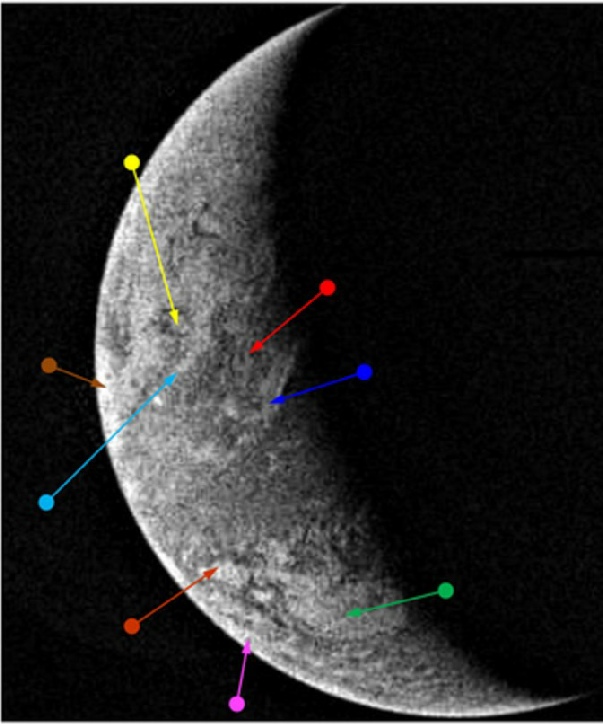

It occurs as part of a short sequence of images immediately before photographs of the jettisoning of the damaged service module part of the CSM, which occurred at 13:14 on the 17th. Prior to this are a number of photographs taken from within the CSM. The Apollo image is shown in figure 4.5.7.3, and the satellite analysis in figure 4.5.7.4.

Figure 4.5.7.3: AS13-

Figure 4.5.7.4: AS13-

As with the previous analysis, the main land mass visible is that of the Indian sub-

There are also clues in the shape of the cloud systems. While there is the same band of cloud covering the Himalayas, the green and blue arrows point to bands of cloud that do not show on the previous day's photographs of the area. The land either side of the broad swathe of Himalayan cloud is considerably clearer than in the photograph taken on the 16th.

ESSA's image, labelled the 16th, still covers this rotation of the Earth, and the most relevant orbital path is number 5184 (track 10), which was commenced at 09:08 on the 17th.

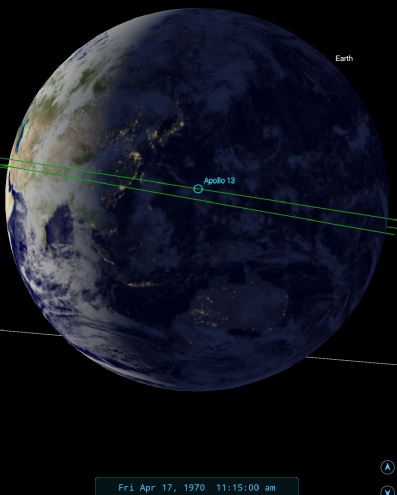

The crew were now only 48000 miles and 7 hours from a safe landing, At 136 hours into the mission (11:15), they ask about settings for black and white film for the upcoming separation from their CM, so the camera was around at this time too. 10 hours earlier, there was a considerable discussion about what cameras were available for photographing the separation manoeuvres, and some concern at the degree of misting on the windows that might interfere with it. This misting is visible on some of the photographs in other magazines.

Speaking of separation manoeuvres, we have one more set of images to look at.

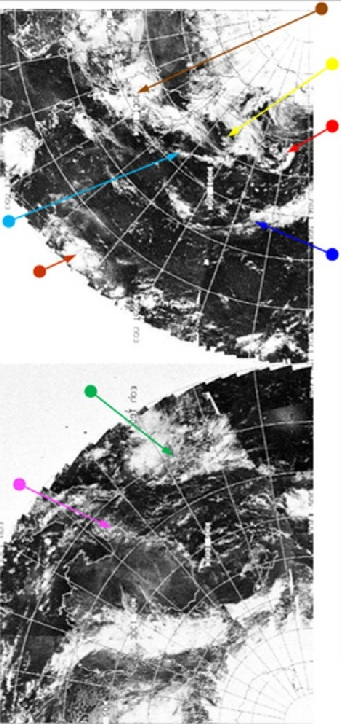

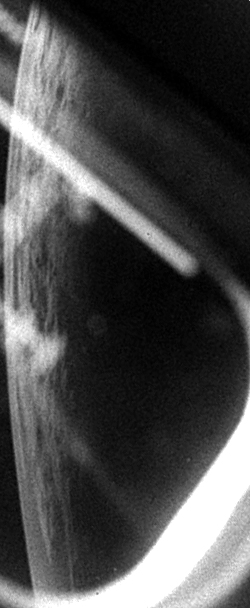

At 16:43 on April 17th the LM Aquarius was cast adrift from the CM on the last lap of their journey home. A series of images was captured of that separation, which occurred just over 11000 miles about the Earth. Sharp-

Figure 4.5.7.5: AS13-

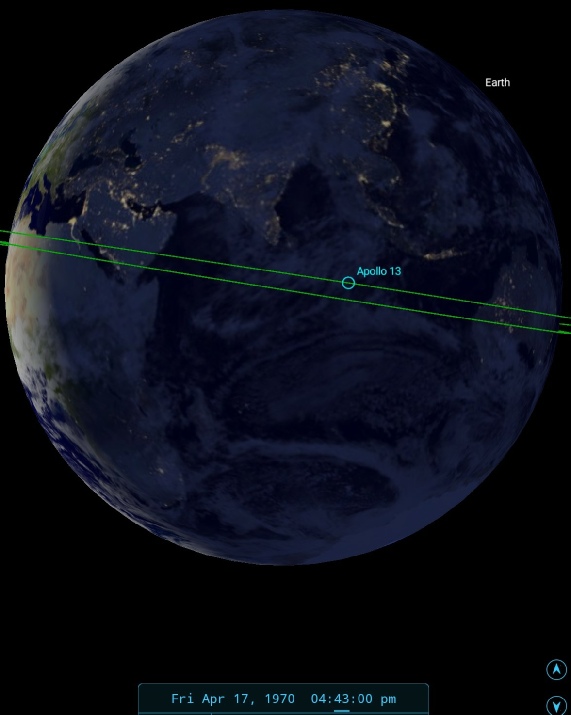

So, can we work out where we are looking? Well, we have a precise time and we have a precise altitude. We also know, thanks to the mission report, the precise position above Earth of the LM at separation (1.23 S 77.55 E), which means we can narrow it down quite a lot -

Figure 4.5.7.6: SkySafari depiction of the view at separation

The terminator is running down the centre of Africa, and realistically not much should be visible in daylight other than eastern Africa and perhaps a little of Europe. The trajectory line indicates that the view is more likely to be of equatorial Africa rather than Europe given the approach Apollo 13 took to its eventual landing site. However it’s also possible that the trajectory could have pointed the camera towards the north or south! It is likely, however, that it is looking along the equatorial region.

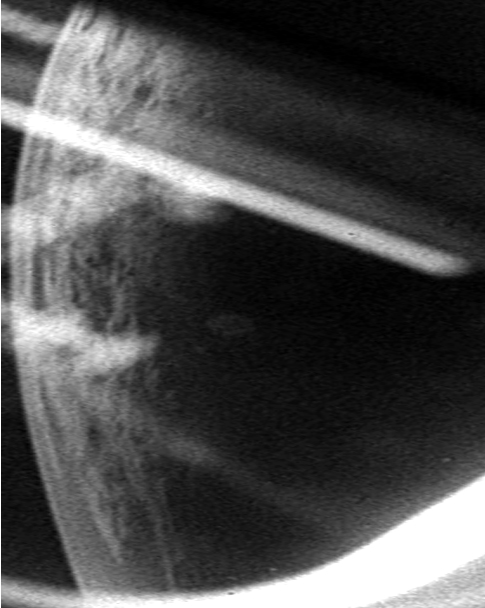

So, we should have a view of equatorial African reflected in the LM window. Let’s see how that turns out. First of all, we need to invert the view of Earth to stop it being a mirror image, and we can also help ourselves in identifying any weather patterns by stretching the view a little (figure 4.5.7.7).

Figure 4.5.7.7: Earth seen in the LM window. The view has been level adjusted and sharpened, and the view on the right perspective corrected.

Can we realistically identify weather patterns here? Well, to be honest not with any great degree of certainty, particularly as we don’t really know how wide an area we are looking at. The width of the sunlit area here pretty much rules out anything other than central and sub-

Figure 4.5.7.8: ESSA image from April 17 of Africa, and a zoom and crop of south-

As I said, nothing I would bet my house on, and I base my judgement on logical deduction rather than precise identification, but for now I am pinning my hopes on the the area I’ve zoomed into above. It’s in the right place and contains the right sort of broken cloud. It’s just a shame that the satellite images aren’t as clear cut as in other examples.

Even if I am wrong in my estimate , what is interesting is that even in images reflected in a lunar module window there are clear details of the Earth and its weather systems, and the clouds even have shadows underneath them -

Apollo 13. Around the moon and home again, with the photographs to prove it.

Click the final link below to look at synoptic charts for the mission.