4.4.8 -

The remaining images of Earth consist of a very slim crescent, so slim that it is extremely difficult to say with any certainty which part of the globe we’re looking at. We can try and do something with the first one available, AS12-

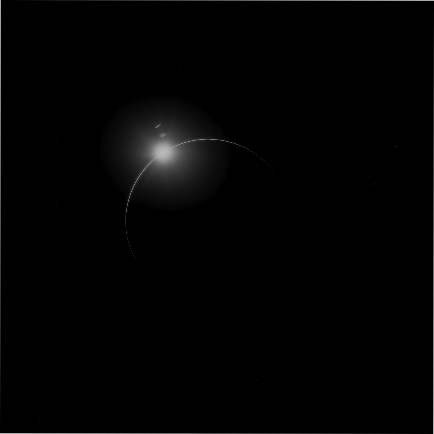

This photograph is described in the Photography Index as “Almost total eclipse of Earth”. Apollo 12 did experience a unique solar eclipse as it passed a point where the Earth completely blocked out the sun. There are, however, a couple of pointers to the fact that this is not a total eclipse. One fact is that by the time of the actual 'eclipse', the 24th, the crew had run out of colour film, and could only shoot the event in black & white. The other major clue is obviously present in the photograph: lens flares. The sun is off to the bottom of the picture (this is even more obvious in subsequent photographs in the magazine but they don't show the Earth crescent as well), so it can't therefore be behind the Earth!

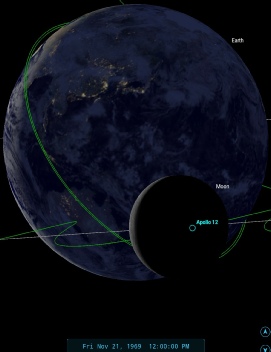

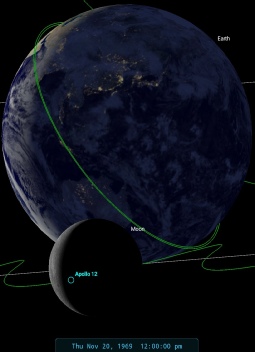

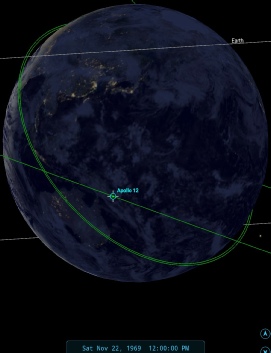

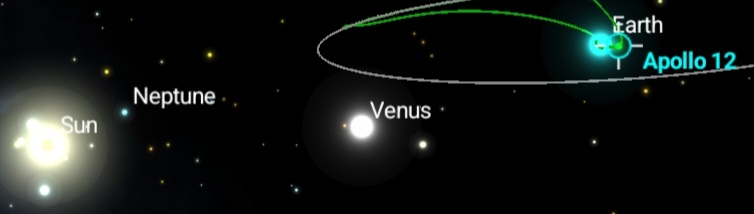

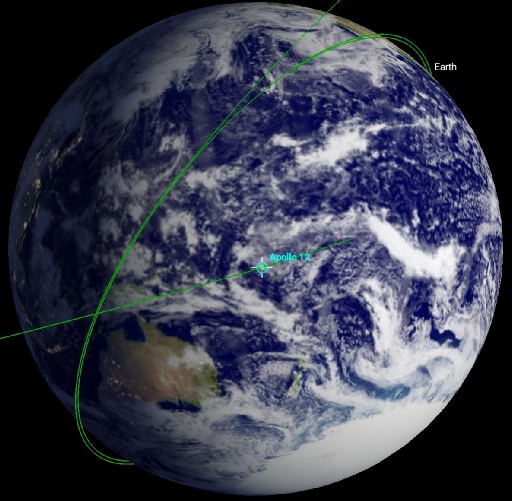

So when was it taken? The image is actually showing the Earth as a crescent continuing to change phase naturally as it has throughout the mission. Figure 4.4.8.2 shows SkySafari views at noon from the 20th to the 24th of November, illustrating the changing phase from a lunar perspective.

Figure 4.4.8.1: AS12-

Figure 4.4.8.2: SkySafari views of Earth at noon from 20-

Looking at these crescent views, the perspective most like that in the Apollo image is that of the 21st, probably later than the 12:00. The whereabouts of Apollo 12 by the 21st depends on when it was taken, as early on in the day it was involved in landmark photography while still in orbit, but at 20:51 it performed a TEI burn.

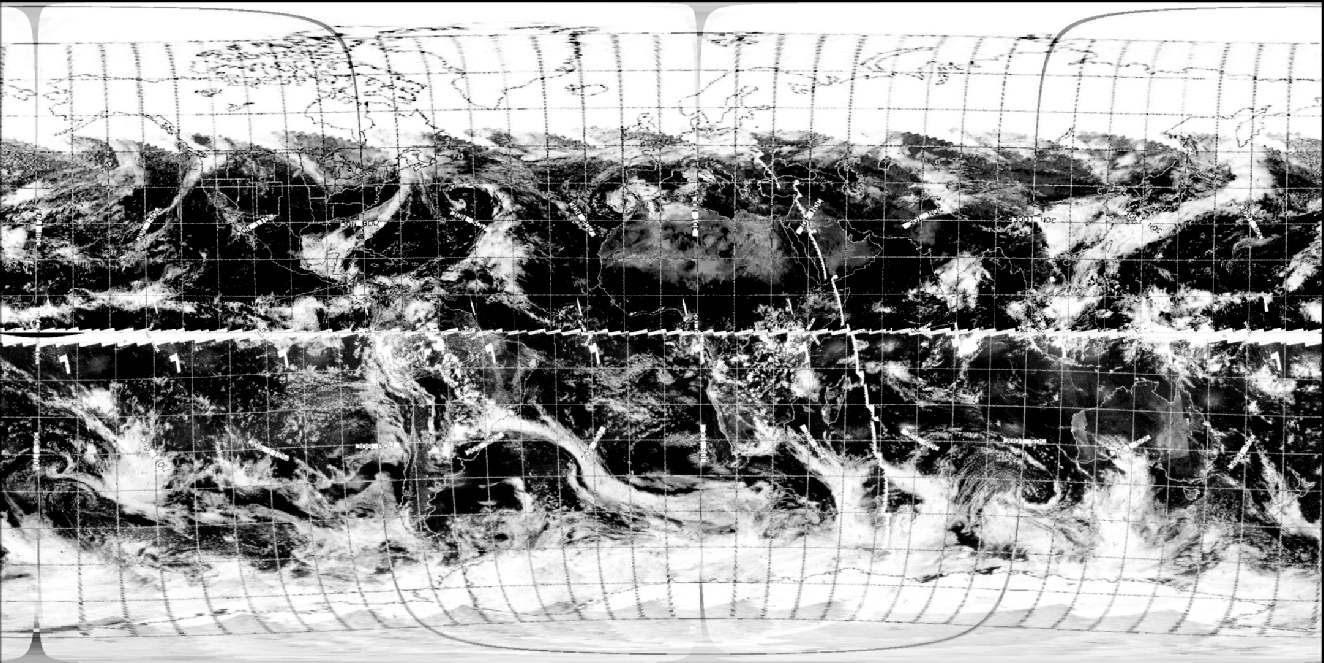

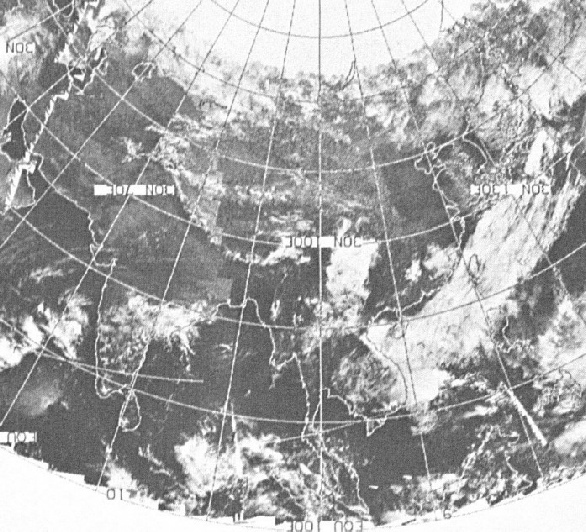

The size of the Earth in the photograph suggests it is much closer to the CSM than the views given in orbital images featuring Earth. The tricky part now is to identify any weather patterns. We have a very small amount of visible cloud, but at least a 24 hour window within which to search. The ESSA image dated the 21st will cover the globe from around noon on that day to noon the next day, so the clouds we are looking for should be visible on that image somewhere.

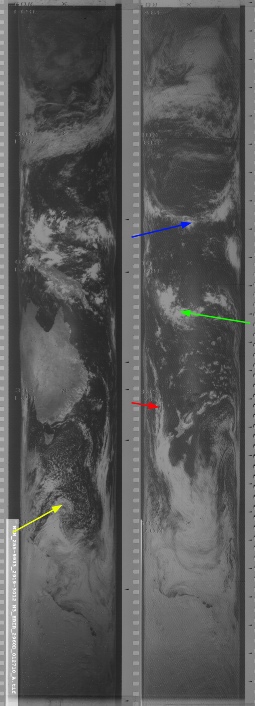

The visible cloud system consists of a large but well defined tropical cloud mass, (at that time of year, the centre line through the widest part of the crescent should roughly equate to the latitude 10 degrees south) to the north of which are high altitude cirrus type clouds and to the south an elongated band stretching south-

For once, there will be no guarantee that the exact cloud has been found, but figure 4.4.8.3 shows the most likely candidate. The clouds arrowed in green are on the line of 10 degrees south, there are wispy clouds to the north of them, bands of clouds to the south. These patterns are particularly evident on the NIMBUS daylight IR image, and the cloud's shape is much more similar to the Apollo image. The pictures from the 22nd bear much less similarity to Apollo, and of course after this the Earth's crescent starts to become much too thin.

Figure 4.4.8.3: AS12-

The exact time at terminator would depend on how much of Australia is visible. In this case at least some has been assumed, giving a time of around 07:30, but I’m the first to concede it’s very speculative. What we can say is that it is consistent with how Earth should appear over the mission timeline.

The NIMBUS image pass that covers the terminator line around the main cloud system is number 2959 from the 21st, which was commenced at 23:40 on the 21st, quite a bit later than the Stellarium time would suggest. ESSA's image, although less like the Apollo photograph, would have been started at around 03:04 (pass 3345 from track 8) on the 21st, with the image used having a date of the 20th. The 3D reconstruction of ESSA data would seem to confirm that we are looking at the right place.

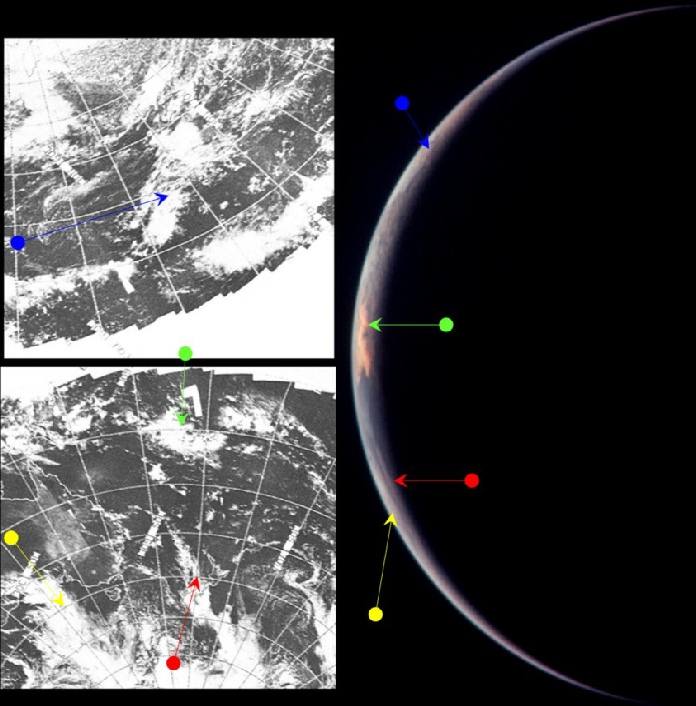

The next series of Earth images are taken as they make their final approach to Earth and prepare to film and photograph the moment of eclipse. A couple of examples are shown below, along with a still from the video sequence showing the eclipse itself (figure 4.4.8.4)

Figure 4.4.8.4: Top row, left to right, AS12-

Obviously we can’t possibly attempt to claim that we can see precisely what landmasses we’re looking at, but we can see if the view the astronauts describe matches up with what they should be seeing. Here’s how they describe it:

241:27:03 Conrad: Houston, 12. We -

…

241:29:03 Conrad: We can also distinguish the lights of large towns with our naked eye, just barely, and by using the monocular, we can confirm that that's what we're seeing.

…

241:29:32 Conrad: I can tell you, there's a couple of ripdoozer thunderstorms down there that are really -

241:29:40 Weitz: From what can you see of the geography there, can you tell where the thunderstorms are, Pete?

241:29:46 Conrad: Okay. I'll give you a fix on this one that is really bright.

241:30:04 Conrad: I'm going to give you a fix and say that it's about 2,300 miles to the southwest of the tip of India. There seems to be a weather system out there, and it's got thunderstorms all the way along it.

241:30:28 Weitz: Roger, 12.

241:30:52 Conrad: It's -

241:32:10 Weitz: Hello, 12; Houston. For your information, weather does not have any surface reports from that region, but the satellite picture does show quite extensive cloud coverage of the area you're reporting the lightning.

241:32:26 Conrad: Okay. I got a -

The first point here is that they are indeed looking down on India and South East Asia. We can also demonstrate that there are clouds South West of India and a lot of cloud coverage over China and Russia, as seen in the satellite view commenced on the 23rd of November, but completed on the 24th (figure 4.4.8.5)

Figure 4.4.8.5: ESSA satellite view of Asia.

It’s also possible to see how the crew could see Venus, even if it isn’t visible in the photographs.

The crew conversation quickly turns to more pressing matters, re-

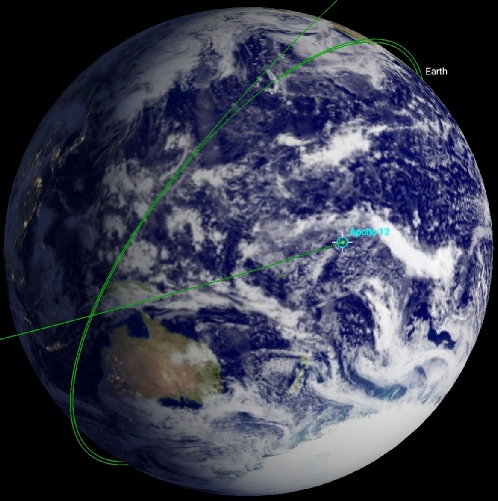

According to the reference work ‘Apollo by the numbers’ the Earth entry interface took place at 13.8 degrees South, 173.52 degrees East eventually splashing down at 20:58 on November 24th at 15.78 degrees South, 165.15 degrees West. Figure 4.4.8.6 shows these locations pinpointed in SkySafari

Figure 4.4.8.6: SkySafari depictions of Apollo 12’s entrey (left) and splashdown (right) locations.

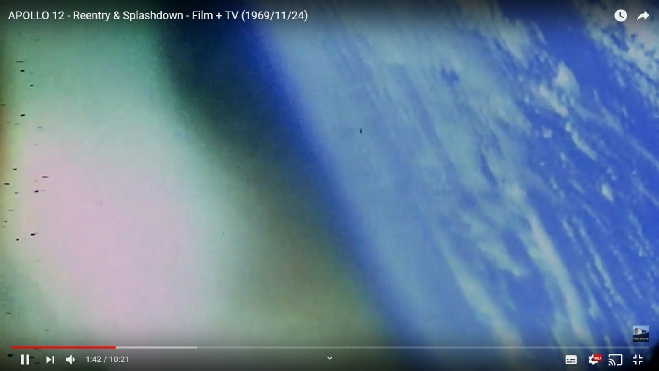

The footage varies in what it shows, but we do get a clear shot from time to time of the ocean below them. Figure 4.4.8.7 shows some stills from the footage.

Figure 4.4.8.6: Screenshots of the Apollo 12 re-

The first thing to suggest is that looking at the trail behind the CM and the horizon in the distance we are still at quite a high altitude here. Can we match up what we’re seeing with any satellite footage?

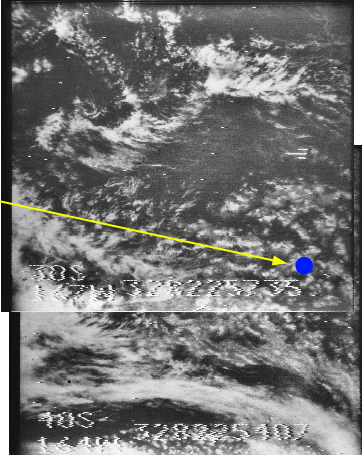

The archives available for this mission don’t have any images for the 24th, but the US ESSA data recovery project does have an image of the southern hemisphere covering that date, and we can combine two of their images to produce a satellite image covering the re-

Figure 4.4.8.7: ESSA and NIMBUS images dated 24/11/69 from reconstructed tape data.

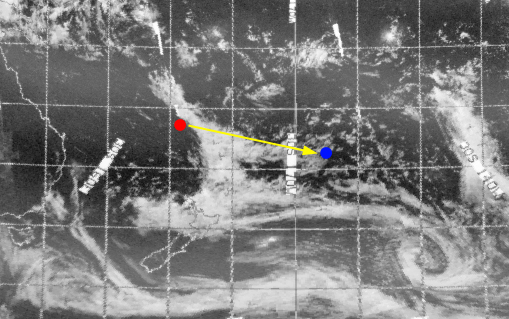

The red marker is the re-

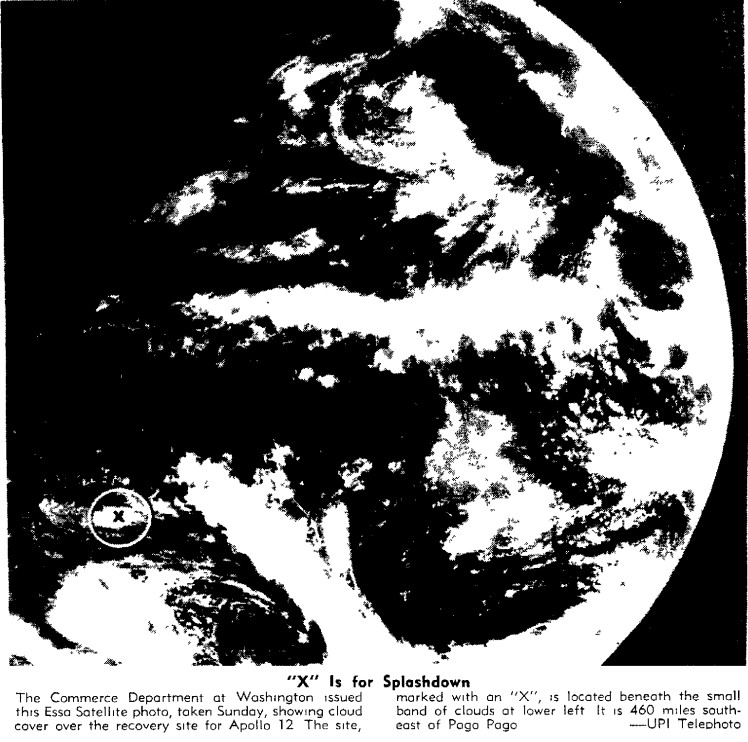

Left: Satellite image of the landing area published in (amongst others) the Oshkosh Daily Northwestern 24/11/69. The image is described as an ESSA satellite, but is more likely to be from ATS-

The NIMBUS tile is clearly marked as having been taken at 22:54 on the 24th, while the ESSA data would suggest a time of between 01:00 and 03:00 to image the landing area.

I don’t think there is a clear enough image to determine exactly where we are looking, but the area to the north of the re-

As always, the sources of information are there for anyone to repeat this analysis and draw their own conclusions, but aside from last one where this is a possibility of doubt, all of the preceding images have allowed a considerably degree of precision in identifying when a photograph was taken, and more importantly from where: On a Moon bound spacecraft carrying three astronauts.