4.9.1-

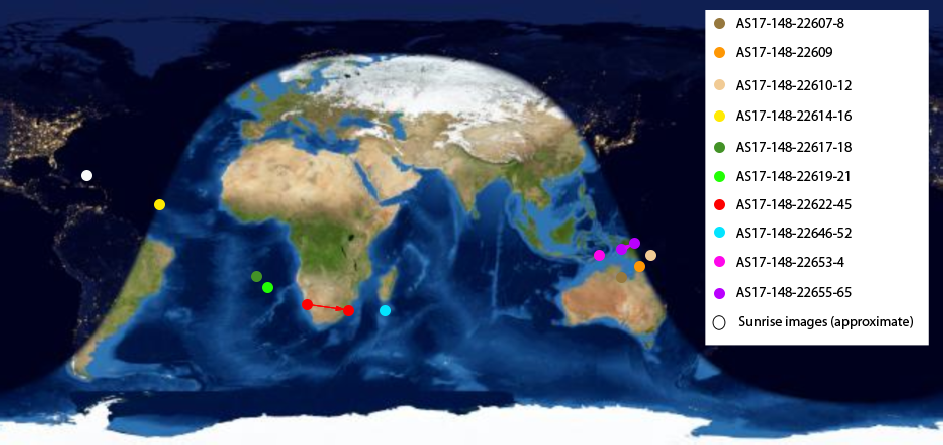

Apollo 17’s launch day is a little different to the others in this series, not just because it was a night one. The crew took far more photographs in Earth Parking Orbit (EPO) than previous missions, and while some are easy to locate, others require a little detective work that necessarily involves including later images out of sequence. It also means we have to split day 1 into two parts to make it more manageable -

To do this detective work we have a number of tools at our disposal, namely the known EPO track of the orbiting Saturn IVB stack, the weather satellite record, the mission transcripts, and the famous ‘Blue Marble’ image (as well as others taken after Trans-

Let’s begin at the beginning.

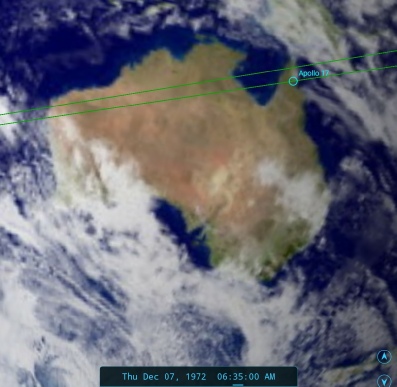

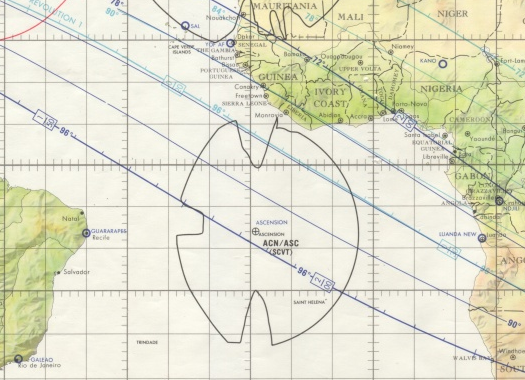

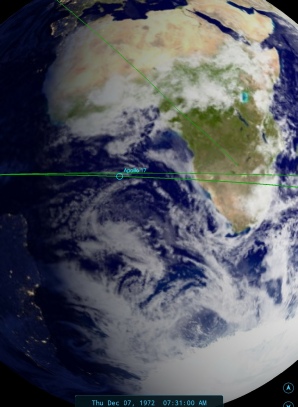

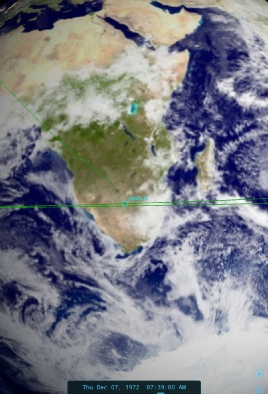

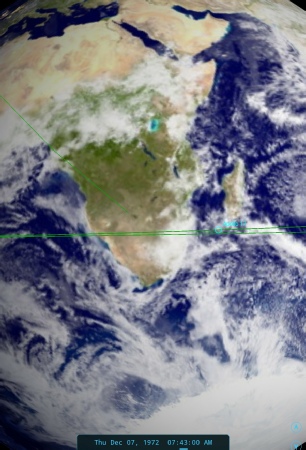

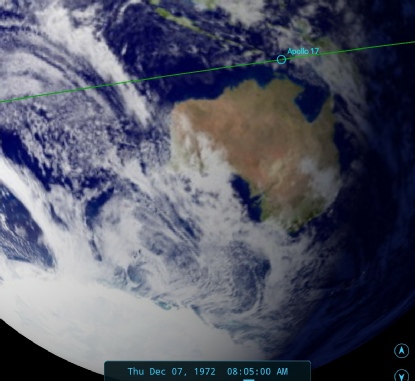

Apollo 17’s delayed launch inserted into Earth orbit at 05:44, commencing the TLI burn procedures 3 hours later after two successful EPO passes. Figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

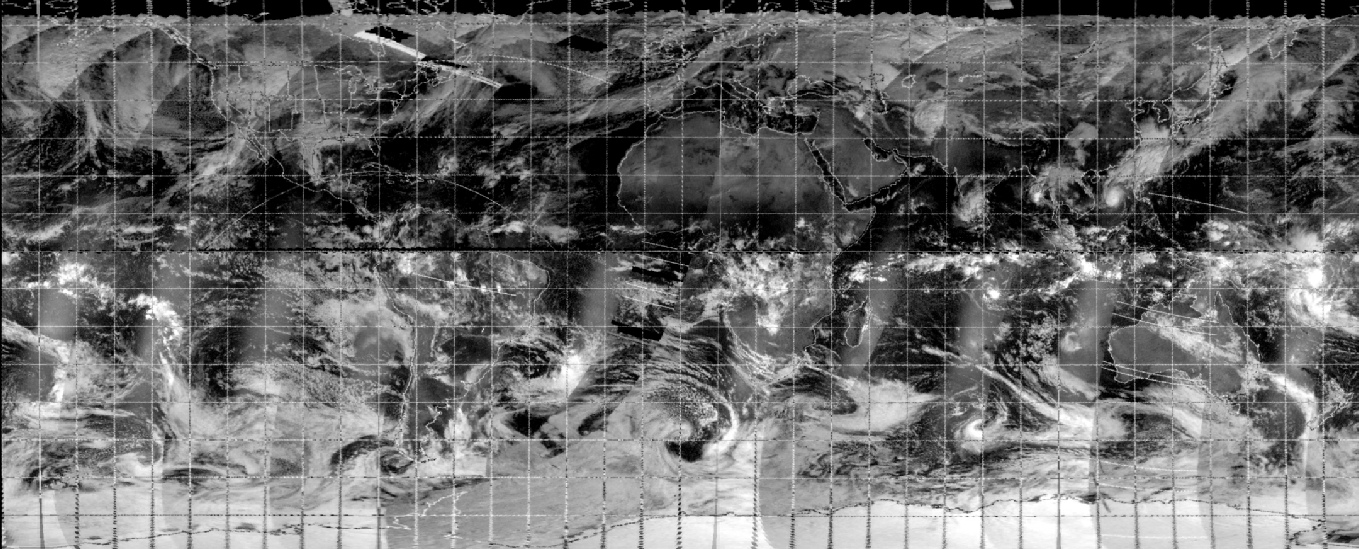

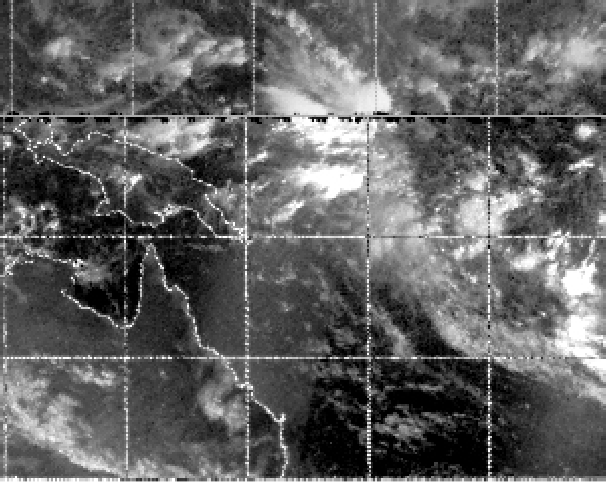

The reconstructed satellite image for the day is shown at the top of this page,and the source for the original document is in the introduction.

The scene is set, the task now is to look at the orbital images and place them on the map

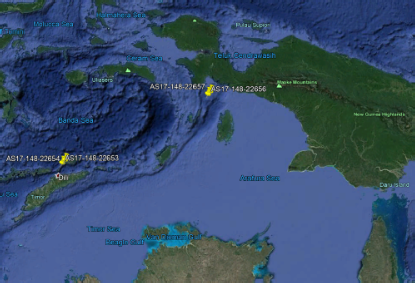

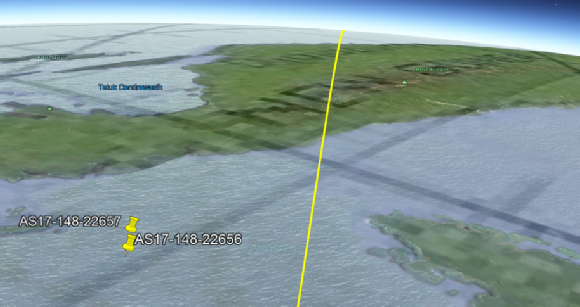

The first shots are pretty easy as their locations are already known. AS17-

Figure 4.9.1-

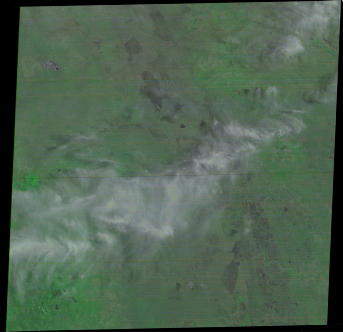

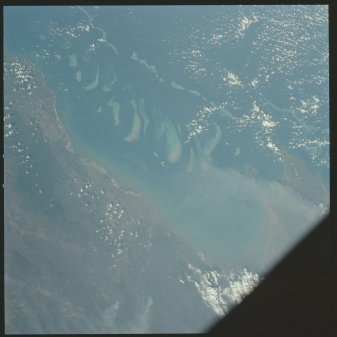

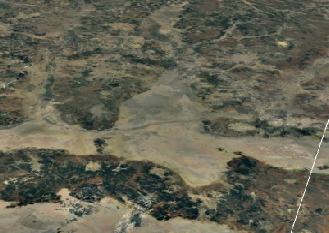

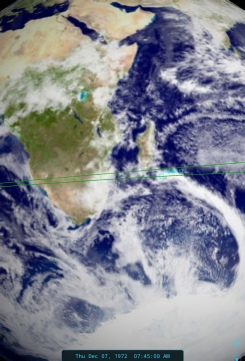

Photos 22607 and 22608 are obviously of the same place, so let’s deal with those first. The Gulf of Carpenteria is the area between the two ‘prongs’ on the north Australian coast, and if you refer back to the EPO charts you’ll see it is clearly covered by the flight path. The photos were taken around an hour into the flight, as at 59 minutes we have this comment:

000:58:03 Cernan: Okay, we're looking at the deserts of Australia right now

At this point communications were being routed through Honeysuckle Creek, as noted by the PAO (Public Affairs Office). This page shows the times of Honeysuckle Creek’s involvement. In terms of where we are looking, the photographs are pretty much oriented in the direction of travel, and we can confirm their location by looking at Google Earth (see figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

Coordinates are 17°19'6.28"S 134°27'23.18"E for the left and 15°51'47.01"S 136°33'48.65"E for the right.

The final photograph in the trilogy is looking almost vertically downwards, and we have confirmation of the time in this exchange:

001:00:33 Evans (onboard): Oh, look at the coral reef there, Geno.

Cernan (onboard): Yes.

Evans (onboard): Look at it; that's coral.

Evans (onboard): Fantastic, Coral atolls.

The coral reef they are discussing is the Great Barrier Reef, and figure 4.1-

The time stamp for the original comment (06:33 GMT) would put them a little short of the location required to take a vertical shot of the reef, hence my suggestion of a couple of minutes later -

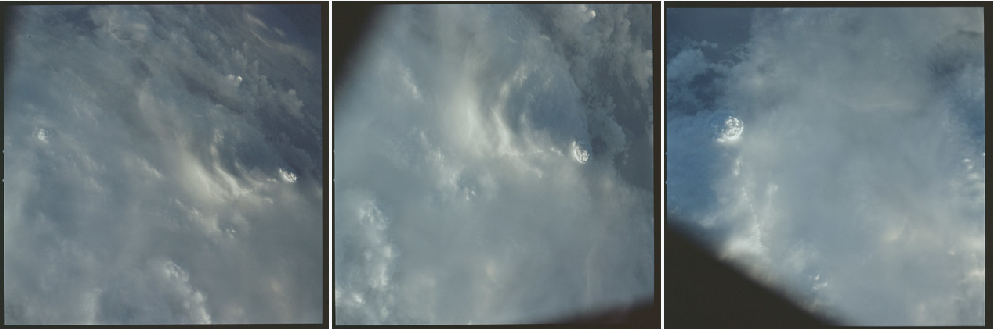

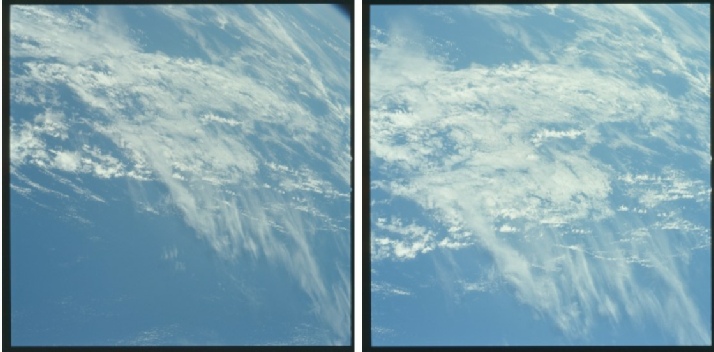

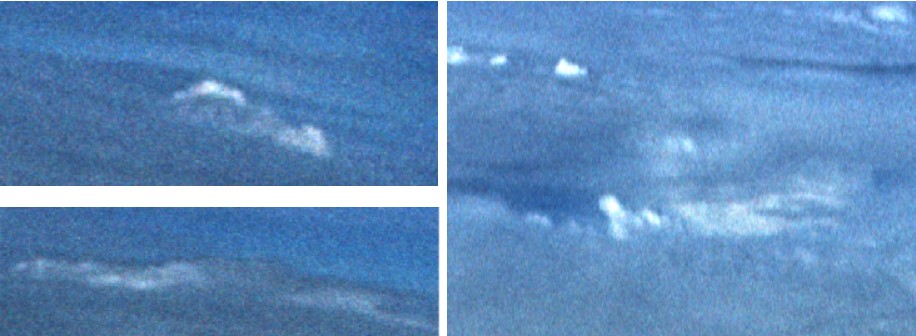

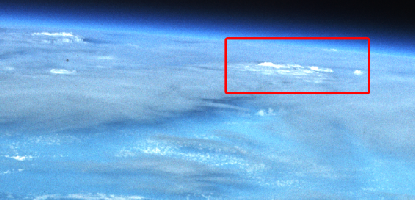

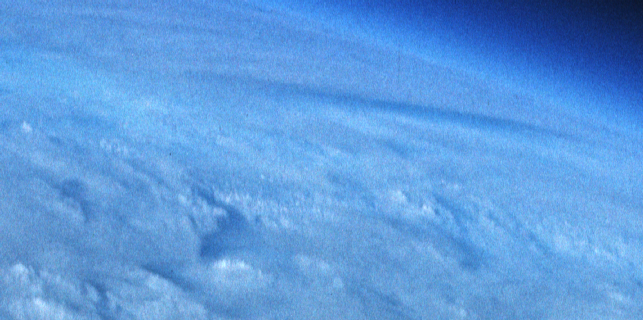

The next sequence of photographs presents a more difficult challenge, in that there are no definite visual clues as to where they are. Figure 4.9.1–1.6 shows the triptych.

Figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

We’re clearly looking at quite an impressive cloud feature, and at 1 hour 9 minutes we have the following:

001:08:56 Schmitt (onboard): There are some pretty lively looking clouds down there.

Evans (onboard): Yes. Yes, yes.

Schmitt (onboard): Better than [garble].

Evans (onboard): Are we going right around the equator, must be.

Cernan (onboard): Yes, we're -

Evans (onboard): [Garble] we went on a 91-

Schmitt (onboard): There's a good-

Evans (onboard): Yes.

Schmitt (onboard): Boy, you could snap a picture of that. [Chuckle.] I forget I got the darn camera.

Schmitt (onboard): [Garble] be underexposed.

Cernan (onboard): I can get that, Jack; give me that.

Schmitt (onboard): I got it.

So, it sounds very like they are talking about this set of photographs.

As it happens there is quite a lively set of clouds along their flight path, shown below in figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

The position of the terminator shows that this lively looking cloud is pretty much on the terminator, and Schmitt (the crew’s resident meteorologist as well as geologist) does point out that:

“In fact, it's a little low-

shortly before the exchange given above.

That storm is approximately 1300 miles from the previous photograph, which must have been taken at about the point the crew were referring to seeing coral atolls. The speed recorded for them at this point is 17443 mph, or 290 miles a minute. The low pressure system identified on the satellite map is roughly 1550-

Unfortunately there are no precise timings available for the Command Module audio transcriptions, and a lot depends on exactly how much time elapsed between seeing the coral reefs and them passing over them for the photograph.

That said, we know that around this time the crew experiences sunset, so it can’t be much further along their orbit, and the time gap between the two sets of photographs is about right. The tropical storm east of Papua therefore seems like a reasonable suggestion for the location of these three photographs.

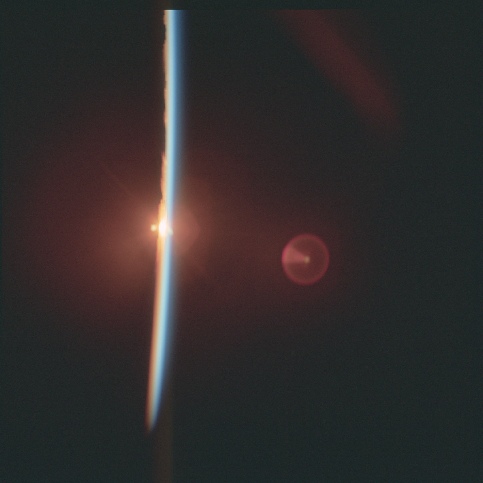

The next image in the magazine (Figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

It’s pretty obvious that we are looking at either a sunrise or a sunset, and not one of the many references we get to an airglow or other lights on the horizon, eg:

001:33:47 Schmitt: Okay, I think we got the Gulf Coast showing up now by the band of lights, Bob.

We know from our maps that sunrise actually occurs over the mid-

There are quite a few exchanges once they cross the California coast that indicate that the cameras have been put down, or away, or misplaced -

Schmitt (onboard): Guess what I've lost?

Cernan (onboard): What?

Schmitt (onboard): Camera.

The crew were also quite busy as the cross the USA with the various check-

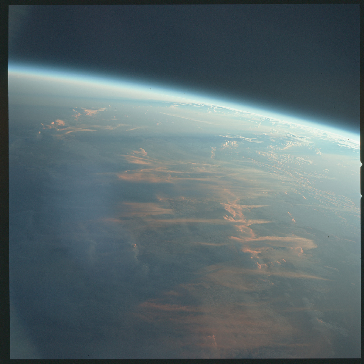

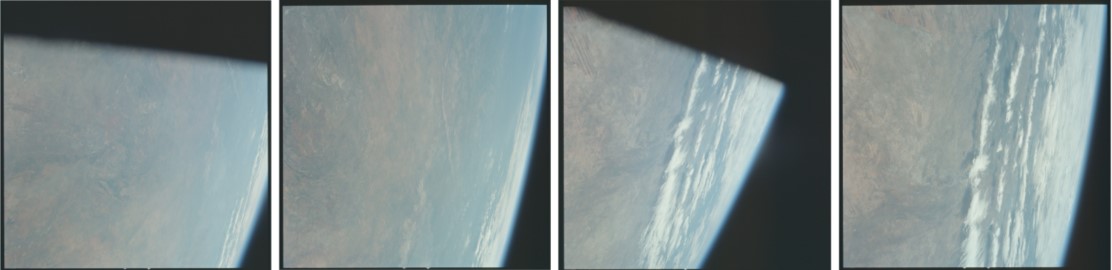

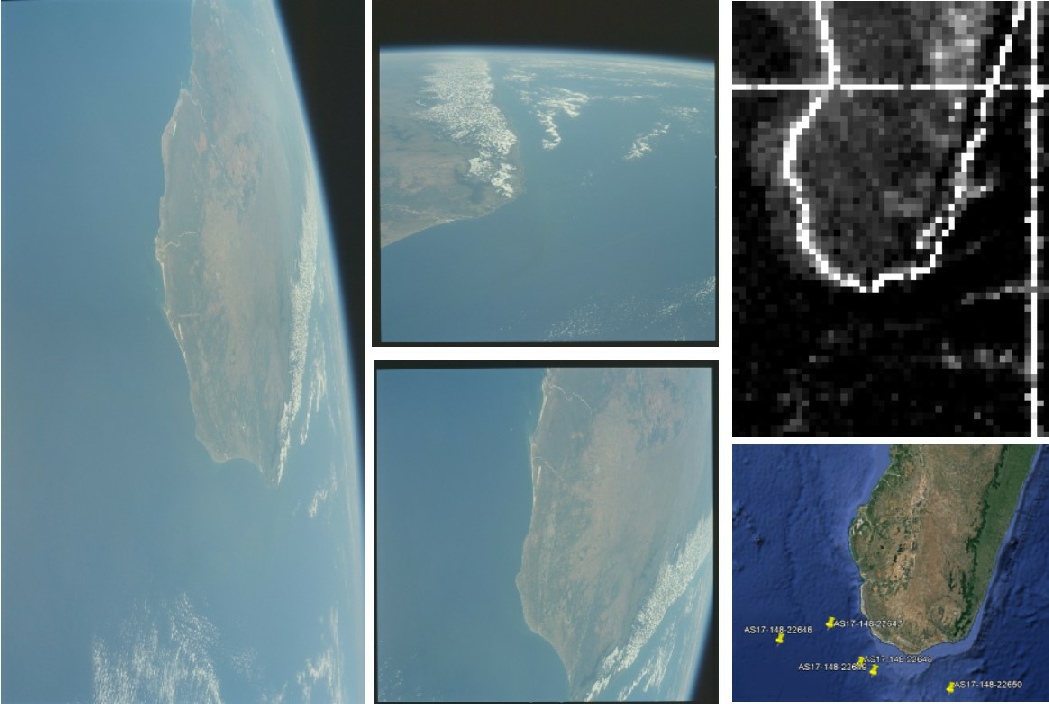

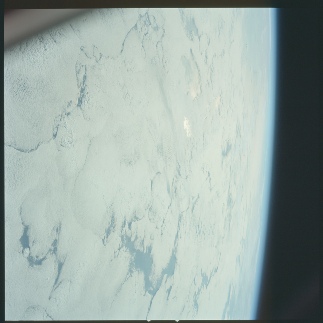

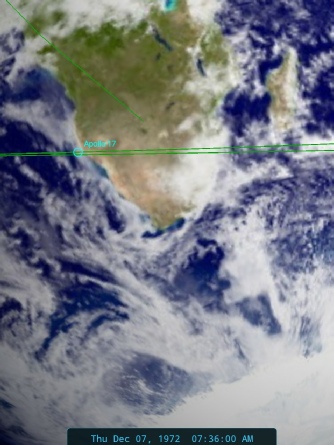

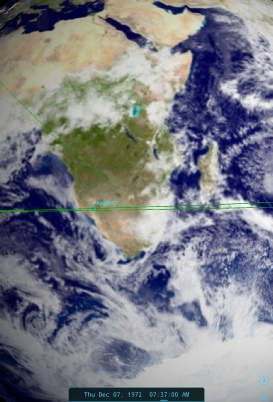

We can be a little more definite about the next sequence of images, given that they start with an obvious only just daylight area of ocean and end, quite definitely, in the African coastline (more about this later).

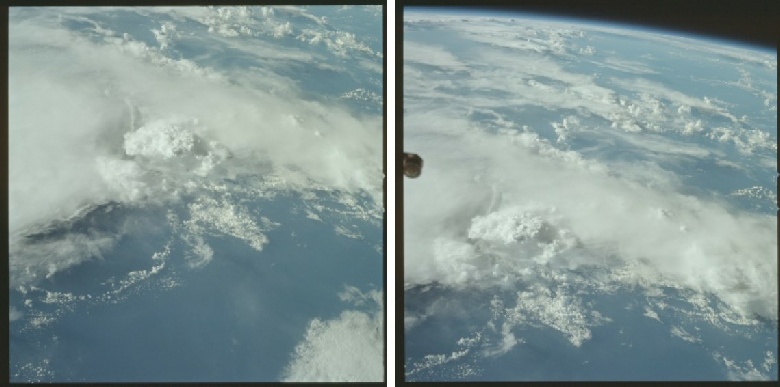

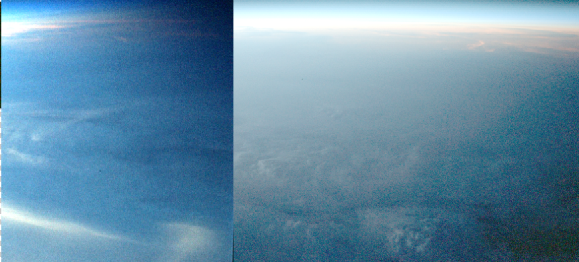

The first three in the sequence are shown in figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

We can tell that these are sunrise images mostly from the slightly darker left hand edge of the first two photographs, but mostly from the hugely elongated shadows of the clouds nearer the horizon.

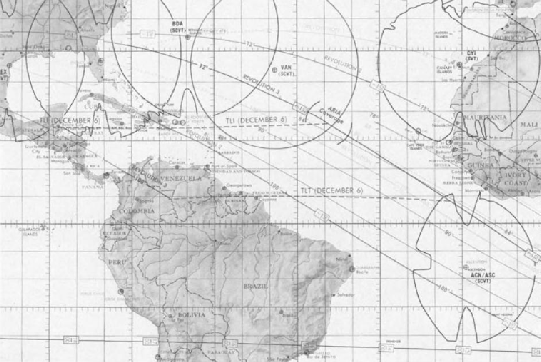

We also have a couple of references in the transcript that allow us to position the photographs. Here we have Schmitt giving us a precise reference point:

001:38:43 Schmitt: Looks like we're right over the Bahamas now, Bob.

Which at this point would still be darkness. We then have the crew losing direct communications with Houston, transferring first to the airborne ARIA system and then Ascension island at 001:51.

17 minutes later we have:

001:55:26 Schmitt: Okay, Bob. We had -

Figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

The evidence of these two maps should put us fairly and squarely between South America and Africa.

We also have the following descriptions by Schmitt

001:56:20 Schmitt: Bob, we're over -

and

001:56:38 Schmitt: Looks like about a north-

which seem to match what he’s describing.

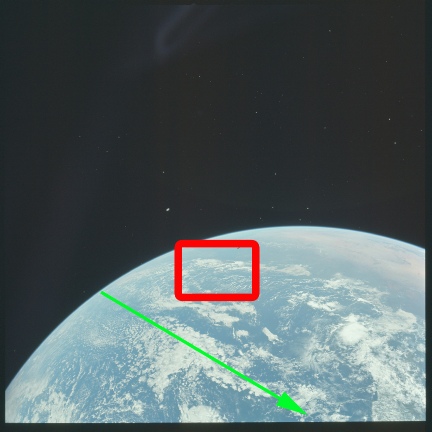

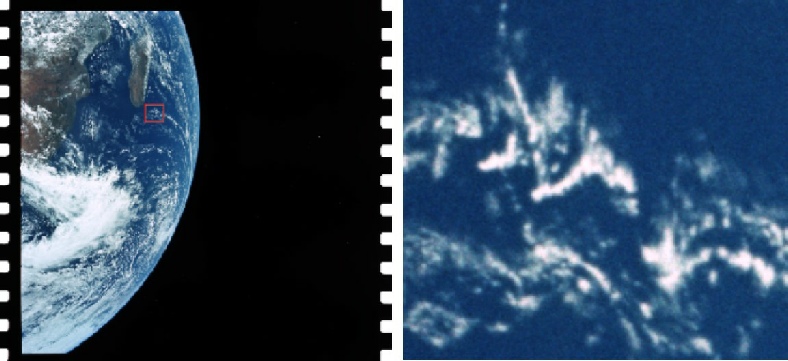

For the third image in this sequence we can bring in a view from one of the post-

The green arrow gives a rough approximation of the EPO flight path, and this is a great help in identifying the location of the next two images.

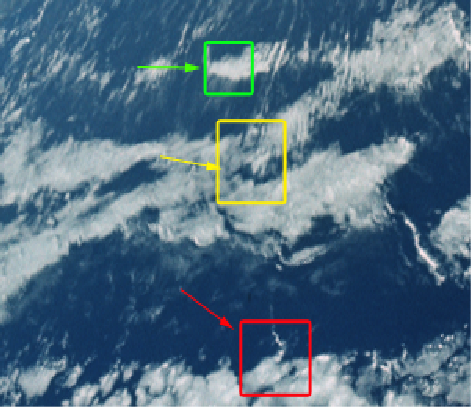

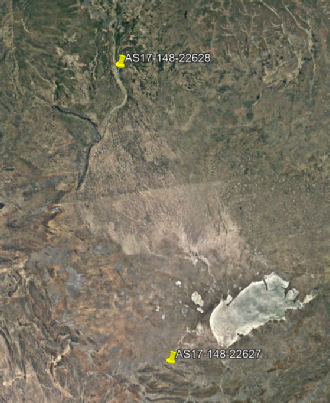

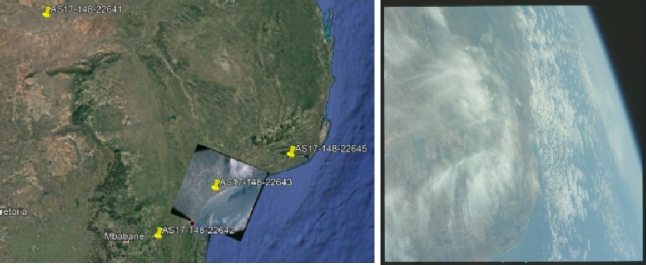

Finding the location of these two (AS17-

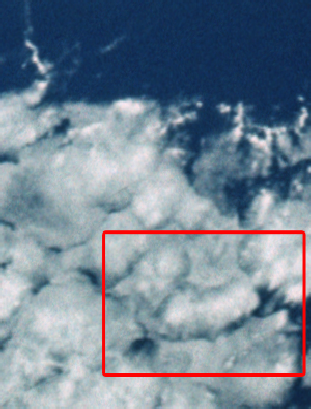

Figure 4.9.1-

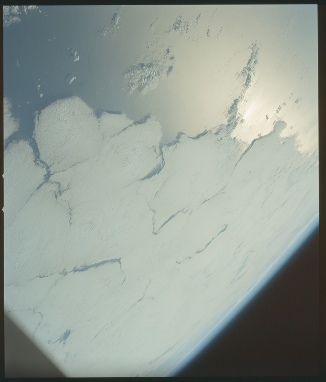

The picture shows an area of thicker cloud viewed looking down and slightly across.The EPO photograph has an area in the post-

We also have an excellent description of what we’re seeing in the transcript, with Schmitt saying:

001:58:26 Schmitt: Well, I certainly am, Bob, and -

001:58:40 Overmyer: Roger. Understand.

001:58:40 Schmitt: And -

An extremely accurate description! Schmitt also waxes lyrical on his website about the view:

“New patterns suddenly jump into view. Over the South Atlantic, between Africa and South America, a solid layer of morning clouds lies crenulated from one horizon to the other like an old washboard. Jagged breaks in those wrinkled strata give the illusion of polar pack ice fracturing and moving apart.”

We now know where this image was taken, and we know what sort of area we need to be looking at, can this help us track down the images taken between sunrise and this one?

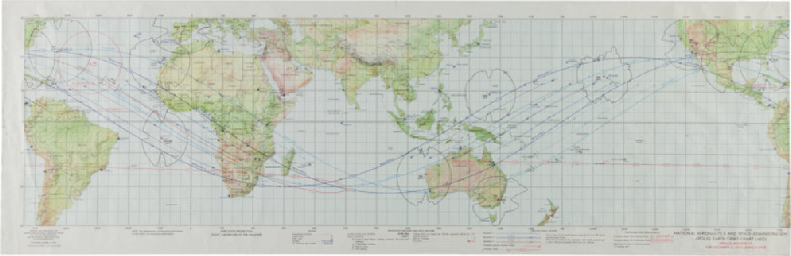

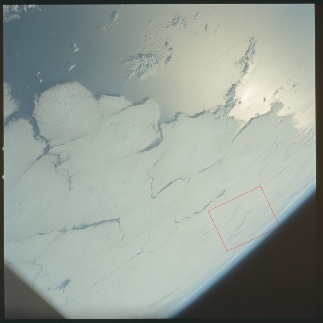

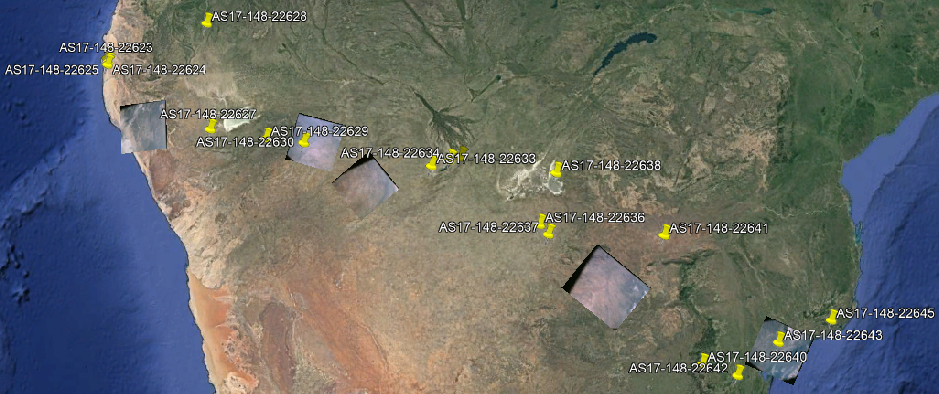

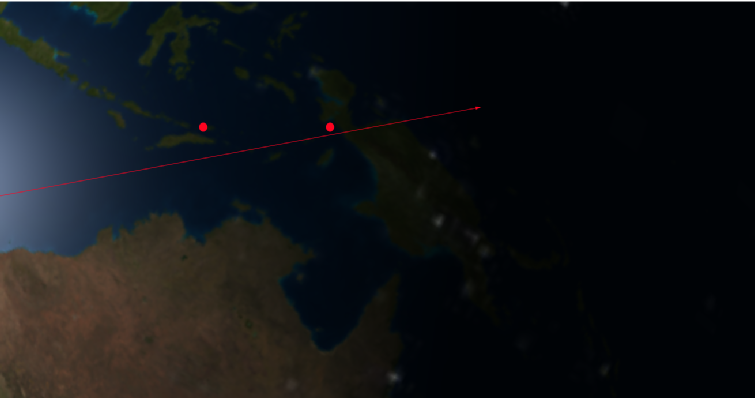

Well, we know the trajectory of the EPO, and we also know where Apollo 17 passes over Africa, which allows us to plot which parts of the Atlantic they crossed on the way to that point (see the EPO trajectory in figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

In the figure above the green box shows the cloud bank in 22617, yellow 22618, and the red box is a reminder of the location of AS17-

Finding the location of the next image isn’t too difficult, as the information you need is also in the one we’ve just looked at. Figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

Can we be sure we’ve got the correct place? Nothing is ever certain but if we look closely at the image we can see that its right hand edge there is much more open water, and the gaps between cloud masses are becoming wider. To the north we have a boundary of thinner cloud, and this seems to be what we have around the area I’ve outlined. I think we can be reasonably confident that we have located another photograph in this sequence.

The next one is again looking towards the east, and we can help in our identification process by stretching the area at the eastern limb to make it look more like the view from above (see figure 4.9.1-

Again, allowing for a couple of hour’s time to elapse and changes in perspective we have a very good match for the location of this final trans-

Figure 4.9.1-

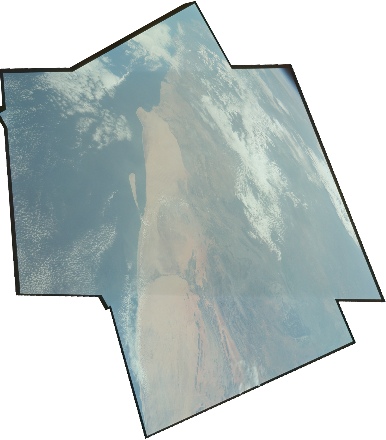

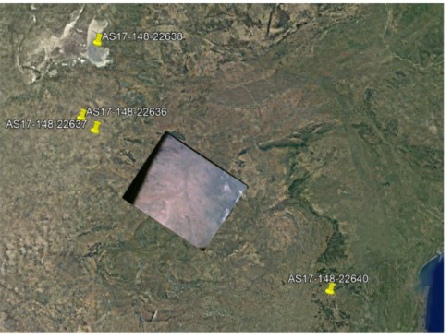

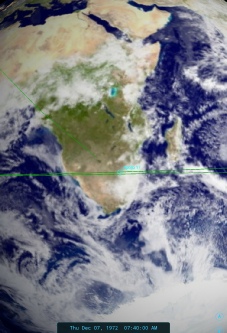

There isn’t much we can add here as it’s pretty obvious that Apollo 17 took these images as they passed over the coast at the Angola-

After crossing into African airspace they continue to take photographs, some looking almost straight down, others at an oblique angle, mostly looking towards the north or in the direction of travel. Figure 4.9.1-

There’s not much to say about these as it’s pretty obvious that the mission is following the well defined EPO path across Africa just as the charts show, but what we can do is show what the oblique images are looking at (figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

The existence of a Landsat tile covering the same weather system visible in the above is an added bonus, and there’s more on that image in the post-

Figure 4.9.1-

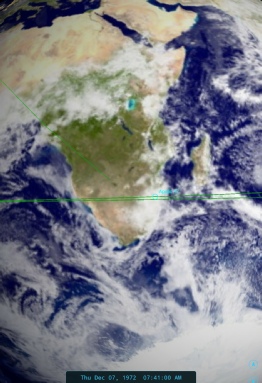

So far so good, and again we have the added bonus of the clouds visible in the EPO photographs also being shown in the satellite imagery from the day of launch.

As with Africa, Madagascar is beautifully clear, as the crew relay to their next point of contact in Australia:

02:28:32 Schmitt: Okay. You've got Omni Charlie. And, Bob, we had almost a completely weather-

002:28:56 Overmyer: Roger.

002:28:59 Schmitt: We got odds and ends on the tape and quite a bit on the film.

002:29:04 Overmyer: Roger; good show. Are you saying that you didn't have any weather over that southern Africa there?

002:29:10 Schmitt: Not very much. Barely broken clouds in some places. Most of the countryside was clear.

The clouds over the high ground on the island are also visibly in the Apollo photograph.

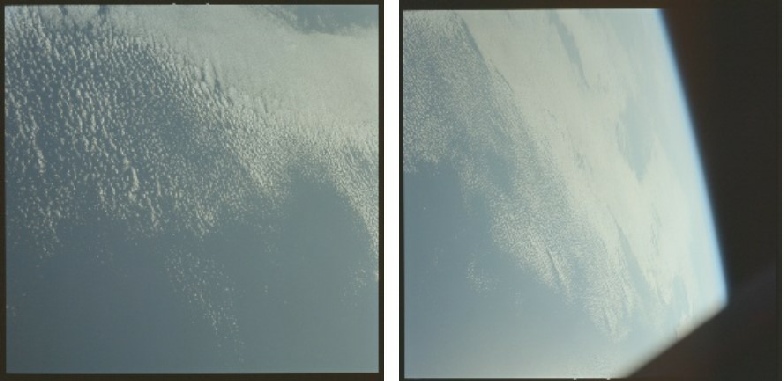

The next two images present more of a problem, as again we are faced with photographs that have no apparent land masses visible, and no transcript record available to help us. Figure 4.9.1-

The second view in particular is one taken at a near vertical angle, so we can deduce that it covers a relatively small area. That said, we can see a small amount of the horizon’s curve. What we can also notice below some of the higher altitude cirrus clouds is a shadow cast on the ocean below, and the angle of that shadow is comparable to the angle of the shadows cast by clouds in the preceding photographs (not to be confused with patterns on the landscape).

The conclusion I draw from this is that these two images were taken at around the same time and location. Are there any clouds we can identify in the post-

Figure 4.9.1-

Can I be absolutely certain that I have the right area? No. Can I be specific about which group of clouds in that area is the one photographed in EPO? No? Is it consistent with where Apollo 17 was at a time when photographs were being taken? Absolutely yes. It’s south-

Leaving that whacking great set of assumptions behind we can now move on to the next set of images. Some of these are easier to locate than others and we sometimes have to delve deep behind the clouds to find their locations. Figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

At first glance we have very little to go on, however if we look carefully halfway down the right hand side of the image we see this (figure 4.9.1-

Where in the world could this be?

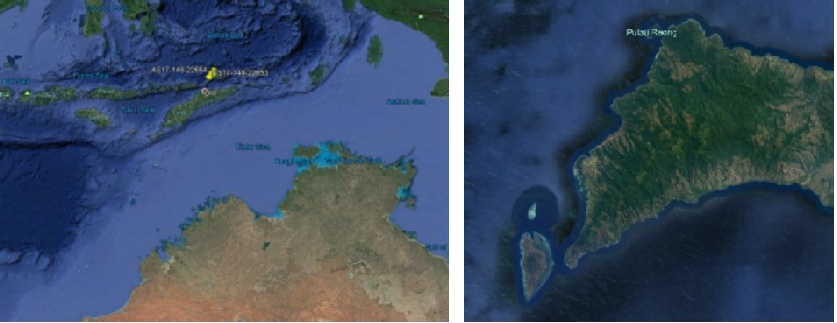

A bit of scouting around on the flight path finds that what we are looking at is the western end of the Indonesian island of Pulau Wetar. It’s shown in close up and in context in figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1.1-

The orientation of the island shows that this view is towards the north from a position below Timor, which is underneath the long bank of cloud across the centre of the photograph. At this point in the orbit they will have just passed out of contact with Carnarvon on Australia’s west coast but are sill out of range of the next tracking station and are waiting to be picked up by Hawaii. As in the previous gap between tracking stations we have no record of what was said by the crew, and for the location of the next photograph we have to skip onwards to two photographs taken after it. These three photographs are shown in figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

As with the previous apparently oceanic images we have little to go on, but once again if we zoom in closely we can find a useful detail (figure 4.9.1-

We now have a confirmed location for the 2 pairs of photographs either side of AS17-

In a word, no.

We can, however, look at a few indications as to where it might be. One obvious indicator of the orientation of the photograph is in the bottom left corner, where the shadows of the taller more prominent clouds are long. It’s heading towards sunset in this part of the world, and the sun is behind them over the Indian ocean, so we can be certain that we are a still looking roughly in the direction of travel. The presence of the CSM window on the right hand side also suggests a slight change of the viewing angle to the right of the images that followed.

If that is the case then we ought to be able to see some sort of land mass somewhere. Figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

While it isn’t possible to identify with any certainty at all exactly which land mass we are looking at, we can say that we are looking at a land mass, and the only land mass of any significant size in the direction in which they are travelling and from this position is Papua New Guinea. The photo might also help us to identify the location of what comes next, more of which shortly.

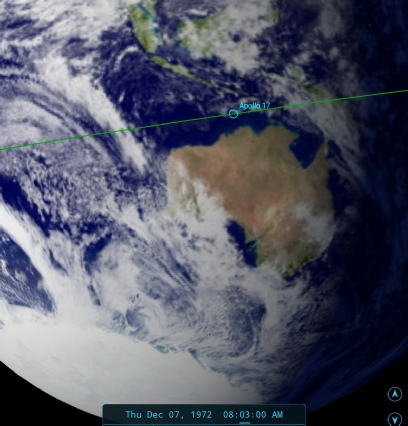

The last set of images in the sequence before the post-

Figure 4.9.1-

We have, therefore, a relatively narrow window in which the final photographs were taken. However, we know where they were going and have a pretty good idea of exactly which path they were following, so we now need to see if we can identify where the following three photographs are showing (figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

The angle of this cloud, the change in direction of the horizon and the direction of the shadows are all suggestive of the camera looking further to the right than the images showing Pulau Adi. The pattern of the clouds are also suggestive of covering a mountainous land mass and then breaking up along the coastline in the distance. The sequence of the images also shows that they are taken along the EPO flight path, given that the final image is taken looking straight down over the cloud mass in the centre of the photographs taken immediately before it. The last photograph also seems to show dark land where any gaps in the cloud can be seen.

Figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

As hinted at earlier there are also possible clues in AS17-

Figure 4.9.1-

As usual, we have to add the caveat that other cloud masses are available, but it is in the right place, and has the right morphology, so it seems a reasonable conclusion to draw.

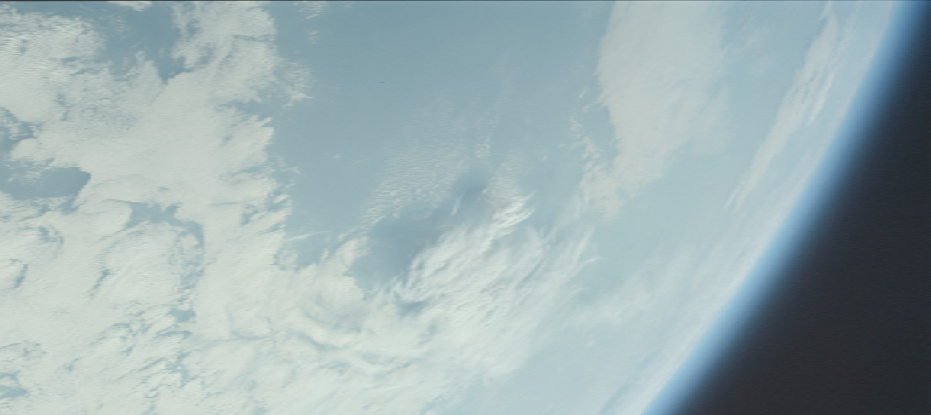

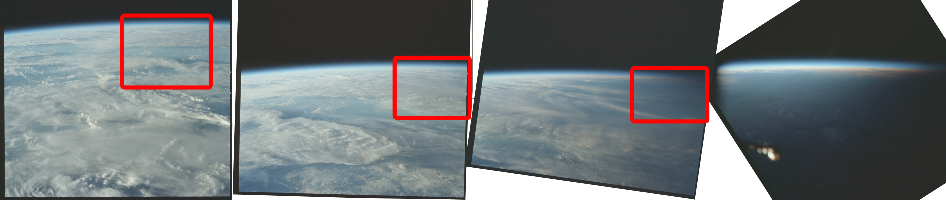

Now on to the final images, taken as they approach the terminator and prepare for the TLI burn (figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

We have the same issue here as we have had with previous photographs in that we have no land mass on which we can pin with any certainty. However if we assume that the last photograph examined is directly over the high peaks of Papua New Guinea and we are continuing to take images in the direction of travel, then we can safely assume that we are looking at the last section of open ocean before the sunset. The angle has changed again, suggesting we are looking slightly north of East than the last images that were slightly south of it.

We can determine that the first image does contain the location of the other 3. Figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

The next question then, again, is ‘can we identify where this is’?

Again, in a word, no, but we can see if there are any areas in other photographs that look similar. Figure 4.9.1-

Figure 4.9.1-

The main reasons for picking out this area are that firstly it lies in the path of Apollo 17, and secondly the presence of the shadow line under the band of cloud running across the photo, together an obvious gap in that cloud and an area of more broken cloud before that.

Conclusive? No. Reasonable? Yes.

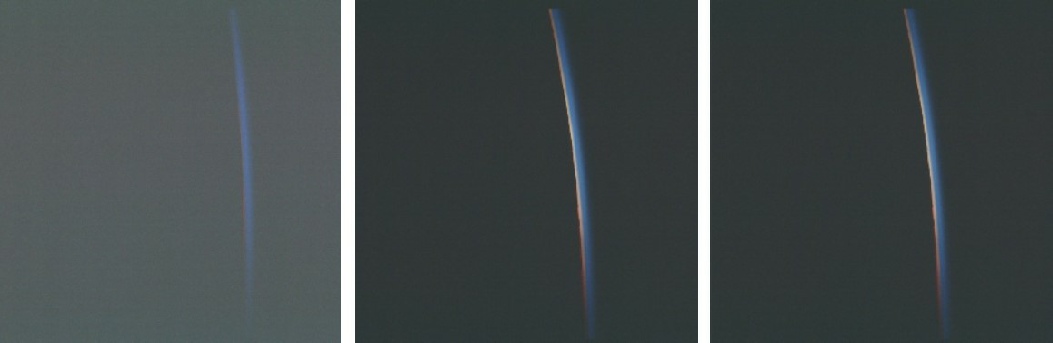

We’ve now, admittedly with some conjecture and guesswork, identified the locations of all the photographs taken while Apollo 17 was in EPO. The final three photographs before we start to see images that are definitely post-

Figure 4.9.1-

They are obviously of the approaching sun, and Cernan mentions that TLI would take them through sunrise.

That’s it, all done. We now have a complete map of where images were taken, and for the tl:dr generation, here it is summarised on the map (figure 4.9.1-

That’s it for EPO. Once around the block they fire up the engines and head for the moon, at least part of which is covered in the second part of launch day. Click the link below.

Figure 4.9.1-